View of the gardens, the dancing children statue, and the mansion post-derecho. Courtesy Brucemore.

In 1981, Margaret Hall bequeathed Brucemore, her childhood home, to the National Trust for Historic Preservation and established local management by a non-profit, Brucemore, Inc. Since then, the organization has built a national reputation as a model for cultivating community interaction.

The Douglas Family, original builders of Brucemore, c. 1908. Courtesy Brucemore.

The Queen Anne home at the center of the estate was built in 1886 by Caroline Soutter Sinclair, the widow of the owner of a Cedar Rapids meatpacking plant. Mrs. Sinclair exchanged the home with that of another family, George and Irene Douglas, who were seeking to move to the country, in 1906. The Douglas family had ties to several major businesses, including Quaker Oats and Douglas Starch Works, which was at that time the largest cornstarch producer in the world.

The Douglases gave the property the name of Brucemore and tripled its footprint. They hired O.C. Simonds, the father of the Prairie Style school of landscape architecture, to design the property. Prairie style landscape architecture strives for a natural rather than an artificial appearance and includes plants found locally in nature. The Douglas family made major changes to the estate, including adding a swimming pool, building several additional buildings to provide housing for servants or space for extracurricular hobbies, and investing time in the landscape. They added a Formal Garden, several specialty gardens, a human-made pond, and several other features to the property.

The historic gardens at Brucemore, c. 1910. Courtesy Brucemore.

The eldest Douglas daughter, Margaret, inherited the property, along with her husband, Howard Hall. They made some quirky additions, including a 1940s version of a mancave in the basement called the Tahitian Room and Grizzly Bar. Mr. Hall also adopted a series of lions who lived on the estate. Mrs. Hall gave the property to the National Trust for Historic Preservation at the time of her death in 1981. Brucemore is one of 26 Sites of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, which is an independent non-profit organization that support preservation activities across the country.

Throughout the last year, the small nonprofit with 11 full-time staff has dealt with dual crises—the COVID-19 pandemic and severe damage from a massive storm. In March, as the nation was just beginning to understand the risks posed by the pandemic, Brucemore shuttered its operation and ceased visitor programming. As Brucemore began finding creative ways to re-open, a massive storm with hurricane-like windspeeds swept across the Midwest in August and caused significant damage. The derecho

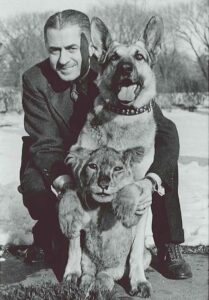

Howard Hall with Leo the Lion and King the German Shepherd, Courtesy Brucemore.

storm destroyed 70% of the mature tree canopy and caused severe damage to seven historic structures that contribute to the site’s interpretation, two modern buildings that support the operation, and multiple pieces of fine art across the estate.

Although Brucemore had a disaster plan in place, the pandemic made everything much more difficult. Communication infrastructure was disrupted across the city and Brucemore and much of the surrounding community had no power for several weeks. Fortunately, an increase in preservation work made possible by philanthropic support within the community prevented damage to the mansion’s interior. While recovery efforts continue eight months later, the Brucemore Board of Trustees and staff remain optimistic about the opportunity to restore the landscape, a rare example of Prairie Style landscape design by OC Simonds and the Country Place Movement.

Cultural Property News interviewed Executive Director David Janssen of Brucemore:

CPN: Can you tell us what brought you to Brucemore?

Janssen: I have been involved with museum leadership for 27 years. I started working as a curator in a small house museum in Ashville, North Carolina. I worked for the Detroit Historical Society and the Edsel and Eleanor Ford House at Grosse Pointe Shores in Michigan. I worked at Brucemore in the 1990s while I pursued my MBA in the evening. I was excited to return to Brucemore for the Executive Director role in 2012.

A staff meeting, post-derecho. Courtesy Brucemore.

One of the things I enjoy most about the historic site sector is the complexity it involves. We have art, artifacts, historic buildings, and cultural landscapes. We have to consider fundraising, security, community relations, politics, budgeting and planning, among so many other things. I love having a plan and then having to adapt it by 10:00 a.m. because things aren’t going as you thought they would.

I have loved being able to learn all of the skills involved. It is truly a career for a generalist. I’m really glad to have picked up landscape theory and restoration and how to develop a garden’s character defining features, especially since I couldn’t tell the difference between a tulip and a mum right out of grad school. I love that I’ve had to learn about building systems and how a steam boiler operates. A director of a small museum has to learn about so many things in order to make effective decisions. It requires a good combination of ego and humility.

CPN: A little hubris is pretty necessary for a museum director, too.

Janssen: You have to be humble because there’s a lot you don’t know on any of these topics, but you also have to be confident enough to make decisions with the best information you have. That served us well in response to Covid and then to the derecho. When you are hit with two unexpected confluences of crises, it’s good that your profession requires you to think on your feet and learn quickly.

CPN: Being a subsector as a historic site of a subset of the museum field ties you to another set of built concepts. You are in a period home surrounded by a Prairie style landscape in the interior of the United States – yet the garden’s history ties you to the history of gardens everywhere.

The Great Hall at the mansion. Courtesy Brucemore.

Janssen: The challenging part of historic interpretation is deciding ‘Which connections do we go after?’ At the museums that I have worked at that have had landscapes, the understanding has grown in the last 20 years to view landscapes as a historic asset. It is a cultural asset as well as an environmental asset. It is a built environment. Somebody created it. Somebody took care of it. It is very much a story of people and of the evidence of the past and what they thought and valued. It’s fun to link the landscape and the shape and the curve of the design to an artifact or a painting or the architecture of the mansion and the history of the people who worked here.

It gives you so many opportunities to tell the stories that you think are important. It’s been really fun for me, which makes it even harder now to face the loss of 70% of our landscape in only a few hours.

CPN: Do you try to recreate and rejuvenate? What can you do with a severely damaged garden?

Janssen: We were so well documented that this was a choice. A landscape is always going to be an evolving piece of art. The way we interpret the landscape is not to freeze it or make it look like it did in 1920. We will latch onto the character defining features. We will focus on the environmental health of the garden and keep out invasive plants and weeds. We will continue to interpret the way the families who lived here used it and the way the designers designed it in order to tell our stories.

Mansion interior. Courtesy Brucemore.

We use the Brucemore landscape today for concerts, theater, festivals, and plays. We try to do that in a way that preserves the landscape while allowing community engagement. We take advantage of the topography to create natural amphitheaters so that when the play or concert is over, there is not a whole lot of evidence of it.

Utilizing the landscape for events requires us to make choices that are not centered on how it was designed in 1886. We have to allow semi-trailers to drive on the front lawn to put up a stage. We need lamps along the roadway so that audiences can leave safely at 10:00 p.m. when the show is over. We have to find that balance between making sure you can see the history of the estate while allowing for its functional use in our mission as a historic site.

As we work to restore the landscape, we will look to the character defining features. We will stay within the guardrails of the historic design but we’ll find opportunities to improve upon modern necessities and site maintenance where it does not compromise the landscape vision. We also have to be careful about not putting so much into the ground that we can’t take care of it appropriately. We don’t want it to be overgrown or spreading.

CPN: With such a small staff and so much damage…?

Janssen: It is challenging. We have 12 full time positions to implement our full mission. Our buildings and grounds team is made up of three positions—facilities director, landscape manager, and building specialist—and is supplemented by a couple of seasonal positions during the mowing and growing season. They are responsible for 26-acres with seven historic structures plus two modern structures. That’s a lot of work for a dedicated, but small team.

CPN: I can see how ambitious a small institution has to be in order to go beyond maintenance and to serve the local community.

Janssen: Brucemore is in the middle of a neighborhood that has both the highest and the lowest socio-economic levels in Cedar Rapids. Both neighborhoods feed a nearby public high school that does an outstanding job to make racial and economic diversity work at a level no other school in the city does. There is a fascinating kind of micro-environment in the neighborhood.

CPN: Do you provide educational programs for young people?

The nursery in the mansion. Courtesy Brucemore.

Janssen: Families and children are central to our engagement strategy. We welcome a majority of the community’s elementary aged children for a field trip during those years. We also have a three-decade relationship with an elementary school in the neighborhood. They don’t have any green space, so they march the kids several blocks to use our front lawn for free every spring for a field day. Our Founding Director would visit with the students at the end of the field day by asking them, “Do you know who this belongs to? It belongs to all of you. You know you are welcome here.” We try to create a sense of ownership in how we interact and share the site with the community. The strategy is not to have 12 foot fences but “take pride in this, it’s yours too.” Even when we have a really big event, like the Balloon Glow, with 9000 people, people feel this is their place, and most are very respectful. We take pride as a staff in trying to create an environment that feels special, but isn’t exclusive.

CPN: Let’s talk about funding in ordinary times and now in this crisis. And volunteerism, via funding and otherwise.

Brucemore director David Janssen at a public kickoff event in 2019. Courtesy Brucemore.

Janssen: We have been blessed by how our community appreciates Brucemore’s existence and role in creating a better place to live, work, and play. The founding director and her successor built an organization that took preservation seriously, but emphasized that our mission is to make Brucemore relevant for people. Over the past 40 years, we have tried to be very innovative. We seek to find a balance between preserving the physical resources and using the site. In having the Joffrey Ballet, blues concerts, outdoor theater, concerts, we’ve welcomed over one million people to the site since 1981.

Doing all of that while creating a sustainable financial structure has been challenging. The original founder and donor was Mrs. Hall. When she died in 1981, she left the property to the National Trust with a $2 million endowment. If you own your own property, it’s easy to consider how expensive maintaining seven historic structures, two modern structures, thousands of artifacts, and 26-acres of landscape could be. It simply wasn’t possible for us to continue to preserve the property under those circumstances. Preservation is expensive, and only becomes more expensive with time.

When I started at Brucemore, I began to work on sharing the need to increase funding to care for the site with community members. In the first 30 years, Brucemore only took in $500,000 total as pure donation. We needed to change that model. After several years, we launched our first capital campaign and successfully raised over $5 million to support major preservation work.

A community event, post-derecho, using broken branches for decoration. Courtesy Brucemore.

Prior to the pandemic and the derecho, we felt really good about how we were positioned for the future. These crises required us to evolve again, but how fortunate we are that we had built strong community philanthropic support. People rallied around us because they understood the impact we make within the community. People understood that we could be part of the economic recovery. By supporting us, we attract tourists and stimulate the cultural and artistic life of the community. We believe in working with other non-profits and cultural organizations and part of what I do is strategize with other organizations to maximize that impact. We partner with Theater Cedar Rapids; Orchestra Iowa; SPT Theatre, Iowa Ceramics and Glass Studio, and so many others. We provide venue space for hundreds of artists every year to explore their craft and to find their audiences. We are a resource. We are a home.

CPN: How are other institutions that are similar to yours faring under Covid?

Janssen: Homes and historic sites are struggling, especially those that rely heavily on visitation and member revenue. I don’t think any historic site can survive on earned revenue. For a historic home to be a large enough organization to be able to manage preservation on an annual basis, you need to have an endowment or government or university or some other funding relationship.

Organizations that have diverse revenue streams and have been nimble enough to pivot at least temporarily to online and virtual outreach have kept their audiences intact.

Going virtual has always been a tricky topic for historic sites because the experiential power of place is a differentiator. For 25 years, I’ve been telling interpretive guides, “If you can tell the story you’re telling right now just as effectively in a lecture hall, then you’re not utilizing the physical space. You’re supposed to be interpreting what they are experiencing, whether they see it or hear or smell it.”

It’s one thing to understand the strategies of the battle of Gettysburg, it’s another thing to be standing on that field. I think that we have to be very careful as an industry not to concede that advantage that we have, which is the experience of being present. But I think there has been really good virtual work done by museums. The enormity of the virtual output is incredible, just to keep people engaged. It can be challenging to generate the revenue necessary to fund the staff and resources required to create it and to create it well.

CPN: Really big museums have the resources and staff to have gotten much more video oriented. What are you doing online?

Janssen: We approached virtual programming and video very cautiously and realistically. We wanted to commit to doing things online that we could sustain beyond the pandemic and also do well. We were able to utilize some rich content and photographs that we hadn’t previously been able to share, as well as to create and participate in virtual presentations and discussions. We’ve received really good feedback from the things we have done and will likely continue to find targeted ways to engage people virtually.

In December, we had a virtual celebration because we weren’t able to host our annual trustee reception. The 30-minute video included footage from the concerts we had earlier in the year. It illustrates what we went through this last year, but also captured who we are as an organization very well. It shows the site’s history, music produced for our programs, a tour of the storm damage and home movie shots at the end of Howard Hall wrestling with his pet lion here at Brucemore. We also demonstrate how a drink that Howard scratched on the wall of the Grizzly Bar is made.

Link to Brucemore video.

CPN: Funding has been very challenging for many cultural nonprofits. How are you dealing with that?

Tree atop the 1915 greenhouse, post-derecho. Courtesy Brucemore.

Janssen: At the start of the pandemic, we had just approved our budget for the fiscal year. It required our staff to look really closely at where we could cut expenses. Like many non-profits, our budget is built to balance at the end of the year so it is really difficult to find places to cut when revenue sources are limited. As a subsector in the non-profit field, museums and cultural organizations face challenges of being excluded from emergency funding.

With Covid, like a lot of nonprofits, we couldn’t show the loss of revenue required for emergency funding, because we didn’t earn a whole lot of revenue. That was really hard for a lot of nonprofits. There were moments there, first with Covid and then the storm, when we felt like the cultural nonprofits were excluded from both tables.

When the derecho hit, we began working with our insurance company, as well as FEMA, to cover disaster response and necessary repairs. Overall, we estimate $2.5 million in damage to the structures and landscape. Both insurance and FEMA have their limitations in what they are able to cover, so we will have to find other revenue sources.

We are fortunate to have a number of donors who care greatly for Brucemore and have given additional gifts in the wake of the pandemic and the derecho. We’ve also been able to apply and receive some other emergency funding and grants from community and state organizations.

This extra work adds a weight to the already full plates of our small staff. Our Development Manager went from managing the capital campaign to learning how to navigate FEMA applications and reporting. FEMA will cover some of the landscape clean-up that insurance won’t. This requires us to think about really detailed aspects like – do you want to submit this bill for this chainsaw blade sharpening? Did you sharpen that blade to cut a tree down that landed on a building or did you sharpen that blade to cut a tree down that landed just on the yard? Because if it fell on a building, that should be an insurance claim. If it’s on the yard, that’s a FEMA claim. We had to go back to our staff and say, you know that blade you sharpened September 16th? How did you use it?

We lost more than 400 trees. FEMA needs to know the GPS coordinates of the stumps. They want the GPS coordinates on every tree, and the diameter. The burden of getting that money is pretty high, but we are navigating it by keeping good records.

We anticipate several audits over the course of the next few years but we’ve invested the time to do what’s required for tracking time and resources. This helps the government and granting organizations ensure the money is being spent appropriately and adds a necessary level of transparency but is really complex and time consuming. We’re fortunate to have had the ability to pivot and take on these extra responsibilities to help minimize the financial impact on Brucemore’s future.

CPN: Have you shared these lessons with other museum directors? This was a far more damaging hurricane event that anyone expected and a catastrophic loss. Are there professional organizations or conservation organizations that you went to outside of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, or have you been on your own?

Janssen: Our existing professional network of both local and national museum professionals and community leaders has been invaluable. We found that out during the Covid. In the heaviest days, the greatest months of uncertainty, we were constantly asking ourselves, ‘What is this? How long will it go on? How do we adapt?’

The landscape post-derecho. 70% of the tree canopy was lost in just a few hours. Courtesy Brucemore.

With COVID, we were able to discuss the choices we were making for our institutions and discuss possible approaches together. With the storm, Brucemore was on our own. The whole community was destroyed. It was difficult to travel between home and work. You couldn’t drive a golf cart from one end of the property to another, it was impossible. We didn’t have power for two and a half weeks, at home or at work. The entire community was dark. The sense of isolation in that moment was profound. I don’t think even people in the rest of Iowa knew how Cedar Rapids had suffered.

It was also a pretty busy year – there was a lot going on in 2020. The election year, the pandemic, the political turmoil… The little storm that devastated 75% of the trees in Cedar Rapids didn’t necessarily hit national news, but it was actually the most expensive thunderstorm in the history of the United States. Cedar Rapids and Brucemore were at the center of the worst of it and we felt like after a couple of days that the rest of the country, and to some extent the rest of the state, had moved on. That was tough for the staff because they were digging out, doing a lot of physical and emotional work. And they were living with trauma for months.

CPN: This is reminiscent of talking with museum people in the Bahamas after their hurricanes. They were trying to figure out what to do right now – today – to clear out the moisture in their museum. In the Bahamas, everything was going to rot within seconds. You can’t say, “We’re more important than elderly people who have no place to sleep.” But at the same time, they had something that was important to preserve, and they didn’t want the aftermath to cause greater damage than the actual storm.

Historic landscape manager Aaron Brewer chainsawing a fallen tree, post-derecho. Courtesy Brucemore.

Janssen: My job right now is to help the staff keep their chins up. We were riding high coming into the year because we had such success reshaping our sustainability model. We had to acknowledge both with Covid and the storm that we were in mourning. We had lost something that we were not going to get back. The momentum we had coming into the year to do really cool things with programing and events – Covid has robbed us of that. Our community has lost lives. There are businesses failing. We needed to be mindful of the big picture, but the staff and I had to acknowledge that we had lost something at Brucemore too; what we had envisioned and dreamed could happen would no longer happen. We would have to look forward and redefine who we were going to be. We were just coming out of that in July, getting ready for our first event in the Covid era with mask protocols and an outdoor event with lots of space – we had it all planned out and then seven trees fell on the event space and the property had to be closed to the public for several months.

The adrenaline of recovery takes over. It took the staff six hours to cut enough trees to get home the night of the storm because all of the downed trees kept them from driving out. Three weeks of constant chain sawing later, I had to acknowledge that there’s another mourning process. You’ve got to allow yourself to mourn. Especially for the team working on tree and debris removal. They were spending their days tearing down the trees that they had spent so much time caring for and maintaining, and love as people do who work in nature for a living.

As a staff, we had to acknowledge that we had lost something permanent. You have to go through that before you can throw yourself into rebuilding. Before you can envision how cool it will be again and what great work we can do.

CPN: How are plans for the future moving forward?

Janssen: I think we’ve now identified the possibilities of how we restore the landscape. The work of planning and the process of replanting will provide a good case study that will serve our profession. We have a responsibility as a nationally significant historic site to be intentional about how we replant. Not only will we do the work, but we will also document the process and share what we learn in the process.

CPN: How much damage was there to your buildings and landscape?

Right now, the insurance puts it at $1.5 million to the buildings and $1 million for the landscape. The mansion did suffer roof damage. It’s not as gratuitous damage. It isn’t easy to spot. The west porch of the mansion imploded. The slate roof alone could be a million if we have to do a complete tear off. Every building took at least some damage. The worst structural damage to a single building was that a tree fell on our 1915 greenhouse. Other than the greenhouse, nothing completely collapsed, but everything took a direct hit.

A lot of the trees we lost were old growth trees. We had not had generations of hurricane like winds that culled them either as you would expect at historic sites in the Southeast. So, part of the enormity of the damage in Cedar Rapids was that there were many, many trees that were 70, 80, 90, 100 years old. They had not been subjected to this before. A tornado is very surgical; it picks this house but not that house. Derechos can be 50 miles wide. To have 45 minutes of 110 mile an hour sustained winds with 140 miles an hour gusts across the whole city with almost no advanced warning – these old, big trees had never been challenged like that before.

The insurance adjusters and FEMA people who had gone through all of the hurricanes in the South consistently said this was the worst they’d ever seen. There was just so much damage. In terms of the cultural landscape, I have been talking to two landscape historians that we are going to work with, and they’ve been talking with their colleagues. Because we had so much that still existed from the 1920s plan across 26 acres that was all destroyed in one afternoon, in one hour, they are hard pressed to come up with another cultural landscape that has suffered this percentage of original material loss in one event.

CPN: You seem very, very determined to build something positive for Brucemore and your community from this disaster.

The Tahitian Room created by Howard Hall, as it is today. Courtesy Brucemore.

I mentioned how diverse the history of Brucemore is and how our story is relevant to the community. A historic place provides a continuity, a piece of community identity that is an intangible asset. We take very seriously the way the landscape plays a part in that. That will continue. We are a hardy breed, both by profession and by Midwestern necessity.

CPN: Speaking of the positive – I also need to know about an unusual aspect of Brucemore. Are the Grizzly Bar and the Tahitian Room okay?

They are fine, that’s in the basement and we did not have any water infiltration into those spaces.

CPN: What I loved about the Tahitian Room was that it made it so clear that this was a house that had evolved through multiple families and generations and it had room for some bumptious self-expression too. There are these beautiful landscapes and gorgeous trees and lawns – it all looks very olde worlde and yet there’s a nice little swimming pool. Not a typical Victorian item. The incongruity of that was wonderful and it made me feel good about the place. It had these quirky elements, like a person with a complex personality.

A museum event before Covid and the Derecho at the Brucemore pool. Courtesy Brucemore.

It’s so strange. You’ve got a Victorian mansion with evidence of later Edwardian interiors for the most part, and then in the basement you have a 1930s man-cave with hula girls and all kinds of tacky things on the walls. It’s very kitschy. There is no ostentation. The owners had money and they were going to have some fun. They didn’t care about trying to impress the neighbors with high style. They wanted a pool; they put in a pool.

For more on Brucemore and its recovery and rebuilding, visit https://www.brucemore.org

Mansion interior. Courtesy Brucemore.

The landscape post-derecho. 70% of the tree canopy was lost in just a few hours. Courtesy Brucemore.

The nursery in the mansion. Courtesy Brucemore.

The Tahitian Room, historical photo. Courtesy Brucemore.

The Brucemore mansion and gardens in 2018, before the derecho. Courtesy Brucemore.

The Brucemore mansion and gardens in 2018, before the derecho. Courtesy Brucemore.