Babel: Adventures in Translation is the latest exhibit at the University of Oxford’s Bodleian Libraries. The exhibition runs from February 15- June 2, 2019. Presented in ten cases, displaying over 100 items, the exhibit explores a range of topics central to translation; from the tools used in translation, such as dictionaries and modern day Google Translate, to the role of myth and fantasy, to the creation of language and symbols in the present that will convey meaning to distant generations thousands of years in the future. It encourages us to think about the role translation has played in building a multi-cultural society and what is gained from the exchange of ideas in the translation process.

A translator, working with both a foreign language and culture, often has to deal with different expressions of belief, social environment and experience that are contained within a variety of cultural expressions. A person from a society with an animistic world-view would have names for the spirits that live in trees, in the mountains and in the rocks. Language equivalents would not necessarily exist for a person from a society without such a view, although as societies change, there is certainly carry-over from past allegiances and beliefs. As S. Frederick Starr asks in Lost Enlightenment, Central Asia’s Golden Age from the Arab Conquest to Tamerlane, Princeton University Press, 2013, p 97:

“Is it coincidental that Central Asians, after favoring the practical Vaibhasika school of Buddhism, with its acceptance of sensory perception, the embrace of past and future, and stress on authoritative commentaries, would later gravitate toward the more practical Hanafi school of Muslim law, and toward the writing of commentaries on the translated works of ancient Greek thinkers?”

Some terms and phrases may not be known by speakers of the same language if they are not considered useful for one’s day-to-day existence. For example, a Southern California surfer may have one word for the “snow” glimpsed in far-off mountains. A skier in those same mountains will have many words for “snow” including; powder, pow-pow, mashed potatoes, corn, freshies, and hard pack. For the skier, this information is crucial, telling them how they should adjust their technique as they head down the mountain. It also tells them if they would rather spend the day skiing or wait for conditions more to their liking. The surfer may have a different language to describe water conditions that helps them to navigate the waves. However, if the surfer takes up skiing, then learning the skier’s language about edging in hard pack or floating in pow-pow could increase their enjoyment and keep them out of the hospital.

The exhibit, Babel: Adventures in Translation, is arranged in a series of cases organized around different themes. Case 1, A Confusion of Tongues, explores different means used cross-culturally and even locally within the same language to bridge communication. The 1604 English to English dictionary, A Table Alphabeticall, was created to help Christian men and women to understand the new “harde English wordes” in the sermons; words that had been commandeered from Latin, Hebrew, Greek or French as there were no English equivalents.

Also on display in Case 1 is the Codex Mendoza. Prepared for Emperor Charles V to document Spain’s conquest of Mexico, the document utilizes pictograms, a Mexica form of language to document the history of Aztec conquest and the annual tribute from 400 towns to the Aztec Empire. The Codex also showed the Aztec social life and customs from birth to death through all social strata. A Spanish priest, who spoke Nahuatl and could elicit the images’ meanings from the indigenous painters, annotated the pictograms in Spanish to facilitate the Emperor’s understanding. (Interestingly, Charles V never received the Codex as the French captured the ship that carried it. The book circulated in France and England before it was gifted to the Bodleian Libraries in 1659.)

Case 2: Building Babel showcases a 17th century image of the biblical tower of Babel when its construction was still coordinated by a universal language. The display invites the viewer to consider the long held desire for a universal language that would express a shared understanding of our world.

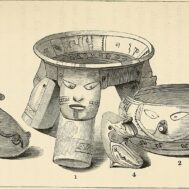

In Case 3, a clay tablet and a stone bowl from second millennium Crete are used as representatives of “Lost and Found Languages”. The early Greek Linear B script on the clay tablet can be translated while that of the stone bowl, in Linear A is still undecipherable.

The failure to translate Linear A has become an object lesson for philologists, and may have inspired Case 10: Translating for the Distant Future. This case explores the creation of language and symbols today that will retain their meaning in future millennia, when our present day languages may no longer be understood. Here it addresses the problem of how to warn about the presence of nuclear waste, which though buried deeply underground will still be a radioactive threat for hundreds of thousands of years.

Beyond Languages is the theme of the 4th case. Here, different ways of communicating are explored. From math to pictograms to lingua franca such as Esperanto, the exhibit asks the viewer to consider the limitations of “universal” communication, pointing out that few things are inherently understandable without some manner of instruction into their meaning.

A beautiful play of script and pattern illuminates a Qur’an on a page from a sixteenth-century manuscript in Case 5: Translating the Divine. This part of the exhibition raises questions of how the divine communicates with humans and juxtaposes the Qur’an – a document considered to be revealed, fully formed in Arabic and untranslatable– with the English King James Version of the Bible; a document created via a translation committee of 47 individuals from texts translated from the original Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek.

An additional point that could have been raised in the exhibition with respect to the process of codification of sacred texts, is that Central Asians, who were not native Arabic speakers, were the key scholars who codified of the Hadith of the Prophet Muhammad, Islam’s second most important text, or note the Central Asian dominance as translators into Arabic (and the preservers) of key Greek scientific, medical, and mathematical texts. Throughout history, a great many important translations have been made by individuals who were not native speakers of either the original or the translated versions.

The introduction to Case 6: Traversing Realms of Fantasy in the excellent Teacher’s Guide to the exhibit makes the statement “…that fantasy and magic are uniquely well suited to being passed on from one cultural group to another. Translators play a vital role in that process – and it’s often futile to distinguish rigidly between translation, retelling and creation.” From the Tower of Babel to Brexit, Bodleian Libraries exhibition explores the power of translation, from the Oxford Arts Blog, notes that the exhibition highlights include, “Different versions of Cinderella – by Charles Perrault, the Grimm brothers, Shirley Hughes, and in pantomime and film – showing how stories have been transferred across cultures, resulting in new interpretations across time, space and different media.”

Similar issues are raised in Case 8: An Epic Journey: Translating Homer’s Iliad & Odyssey and Case 9: Tales in Translation as in Case 6:Traversing Realms of Fantasy. All three cases explore stories, that like Cinderella, “have been transferred across cultures, resulting in new interpretations across time, space and different media.”

The Bodleian exhibition team is also working together with the Arts and Humanities Research Council as part of the Open World Research Initiative to explore the interconnection between linguistic diversity and creativity. The exhibition catalog, Babel: Adventures in Translation, by Dennis Duncan, Stephen Harrison, Katrin Kohl and Matthew Reynolds, will be available from Bodleian Library Publishing after 15 February, www.bodleianshop.co.uk.

As an adjunct to this review, Cultural Property News has included in this month’s news a translation of the Cinderella story collected in Uzbekistan from an early 20th century guild text. See Central Asian Cinderella, the Tale of Bibi Seshanbe, by Kate Fitz Gibbon.

Pieter Breugel the Elder, The Tower of Babel, Detail, The king and entourage visiting the builders, 1563, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Gemäldegalerie, Vienna, Austria

Pieter Breugel the Elder, The Tower of Babel, Detail, The king and entourage visiting the builders, 1563, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Gemäldegalerie, Vienna, Austria