Conversations about cultural property usually revolve around questions of ownership, conservation, national patrimony and public access. From a legal perspective, the origins and provenance of individual artworks or artifacts are of primary importance. Yet from the perspective of an historian, an artwork is not only an object to be possessed and protected, but an active agent in the society that possesses it. Cultural artifacts are not only subject to the policies of nations but may also influence them. Political art in particular plays an active role in history, and with the passage of time may take on new importance, by attesting to the struggles of artists, agitators, and idealists to transform their society. Even when placed under restrictions governing the ownership, sale, and movement of cultural property, art is never passive or inert, continuing to speak to the present moment of its history, and possibly even inspiring further societal change.

Medallion, Am I Not A Man And A Brother? Made at Josiah Wedgwood’s Etruria Factory, Staffordshire, England, 1787-1800, Jasperware (Unglazed Stoneware), Developed in 1787 by the Society for Affecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, Museum Purchase with Funds Provided by W. Groke Mickey, Museums at Washington and Lee University.

The campaign to abolish slavery was waged, both in the British Empire and in the United States, on many fronts. Slaveholders, slave traders, and the many, many other stakeholders in the slavery-based economy resisted abolition by promoting pro-slavery politicians and seeking to silence abolitionist voices. Nonetheless, principled lawyers and individual petitioners fought for the rights of escaped slaves in the courts, while politicians and private lobbyists pressed for government action to eradicate the practice entirely. Meanwhile writers, artists, and artisans produced work protesting against its evils and asserting the humanity of the enslaved. It is with this last group that the history of slavery-abolition overlaps with the history of art, and cultural heritage.

The role of art in forwarding social change is of particular interest in the history of abolitionism in the British Empire, and especially within England, where the bulk of political power lay. Although it took a Civil War for slavery to be abolished in America, in Britain the campaign was waged largely through legal actions, political engagement, and public messaging. Art was a key tool for British abolitionists to promote their ideals. Starting in the early nineteenth century, new printing and engraving technologies made the production of affordable prints possible for the first time, meaning that artworks or designs produced by one artist could reach a mass audience, dramatically expanding their impact.

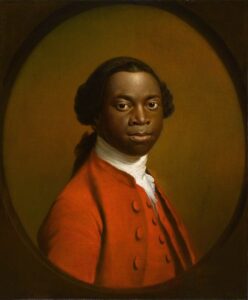

Allan Ramsay, Portrait of an African, c. 1757–1760, (probably Ignatius Sancho, 1729–1780), Royal Albert Memorial Museum (RAMM) Exeter, Devon, UK.

Artists produced works which preserve at least a few of the faces of Black leaders who pressed for abolition in Britain. Charles Ignatius Sancho, who escaped slavery in England and became a successful shopkeeper as well as the first Black man to vote in an election in Britain, was painted by both Thomas Gainsborough and the notable Scottish portraitist Allan Ramsay.

Another popular portraitist, Richard Cosway, included Olaudah Equiano in a family portrait of himself and his wife and fellow artist, Maria Cosway. Equiano, who also went by the name Gustavus Vassa, was then employed as a servant in their household, having purchased his freedom at the age of 21. In the 1780s, he was a leading member of the abolitionist organization the Sons of Africa, and went on to publish an autobiography which was widely read, and which Is credited with directly contributing to the legal abolition of the slave trade in 1807. A true portrait engraving of Equiano accompanied the book, providing a face to accompany its narrative of oppression, and probably enhancing the impact of the book on its readers.

The simple humanity of enslaved Black people was a primary theme of much of the art associated with the abolition movement. Josiah Wedgwood, founder of the Wedgwood ceramics factory best known for its neoclassical jasperware and cameos, also produced art objects promoting the cause of abolition.

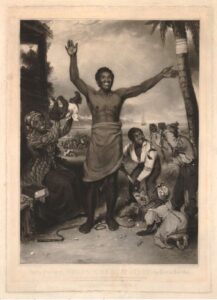

After Alexander Rippingale, To the Friends of Negro Emancipation …, 1834, engraving by David Lucas, published by Sir Francis Graham Moon, 1st Baronet, Hodgson, Boys & Graves, Ackermann, and Charles Tilt. British Museum, London. Also written below: ‘A Glorious and Happy Era on the First of August bursts upon the Western World; / England strikes the manacle from the Slave, and bids the bond go free.’

The image and accompanying phrase shown on Wedgwood’s small black and white medallions achieved widespread adoption as an emblem of abolition, in the UK and in the United States. These objects do reveal the racism which marred White abolitionist movements – the medallion shows a Black man in chains, kneeling in supplication, reliant on the favor of White society for his freedom. Most White abolitionists believed in their racial superiority to Black people, and the medallion design reflects both their sense of common humanity, and yet also of White privilege and power. One obstacle to abolition, and afterwards to full legal equality, was the fear and disdain White people held for Black people, and it has been suggested that this image, and others like it helped to assuage those fears by asserting the humility and gratitude that freed Black people would feel after emancipation.[1]

However, pro-abolition objects such as Wedgwood’s medallions, as well as practical ceramics such as teapots, dishes, and even sugar bowls (particularly potent objects, given the widespread use of enslaved workers on sugar plantations), were all produced in the late-eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. These politically-charged accessories proved widely popular and certainly played a role in disseminating and promoting anti-slavery principles into households across the UK and also in the US.

Art did not cease to address the issue of slavery after its legal abolition. A painting by Bristol-based artist Alexander Rippingale in honor of the 1834 abolition of slavery within the British Empire was made into a popular print showing a group of newly-freed former slaves celebrating their emancipation. A copy of an ‘emancipation notice’ affixed to a palm tree in the background, and a large book, probably a Bible, in the left foreground, convey the two forces that converged to achieve abolition –practical political action driven by the moral and spiritual convictions of its supporters.

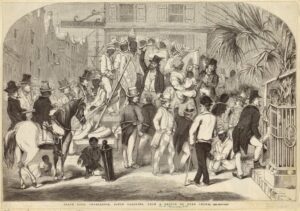

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. (1856). Slave Sale, Charleston, South Carolina : From A Sketch By Eyre Crowe.

Britain’s abolition of slavery did not include an embargo on goods produced by slave-labor, meaning that British tradespeople and consumers continued to purchase cotton, sugar, tobacco and other products from the slave-holding United States and its territories, and British artists and activists continued to campaign against slavery and the slave trade.

In the early 1850s, the British painter Eyre Crowe and William Makepeace Thackeray (already famous as the author of Vanity Fair) travelled to the United States to document what they saw of the slave economy. At least one sketch by Eyre Crowe, of a slave sale in Charleston, South Carolina, was also reproduced and sold as a print.

Joseph M.W. Turner’s painting The Slave Ship, originally entitled Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying—Typhon Coming On, is perhaps the most famous British artwork related to the history of abolition. Although painted in 1840, The Slave Ship represents an atrocity which took place in 1780, on board a British slave trading ship, the Zong. When drinking water ran short at least 130 Africans, en route to enslavement in the Caribbean, were thrown overboard. Some had already died, because of the short supplies and because of illnesses resulting from the horrific, overcrowded conditions on board, but many were still alive when thrown into the sea.

Joseph Mallord William Turner, Slave Ship (Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On), 1840, Museum of Fine Arts Boston.

The incident was well-documented and widely known because of a series of legal arguments which followed, most of which turned, ultimately, on whether the murdered Africans qualified as human beings or as property. The massacre became public when the owners of the ship demanded payment from their insurers for the financial loss of the enslaved ‘cargo’. A second legal case ensued when the abolitionist and freedman Oludah Equiano brought the case to the attention of his ally, the activist-lawyer Granville Sharpe, who sought unsuccessfully to have the ship’s captain and crew charged with murder.

Turner’s image, in contrast to the cold, dispassionate language of legal argument, is immediately shocking. An apocalyptically colored sky, and a sea painted in sickly greys and browns evoke the horror of the scene, where the reaching hands of the drowning people just barely emerge from the tossing waves. The image has since been criticized for its focus on the atmospheric effects of light and water over the realities of the atrocity it depicts, but it remains a powerful image, evocative of two sides of the history of slavery: its real horrors, and the role of art in documenting and protesting against it.

Cup and Saucer, bone china, England, 1810-1830.

An exhibition at the New York Public Library, Subversion and the Art of Slavery Abolition, delves more deeply into this history. Though Black History Month is drawing to its close, Black history itself is an important subject at all times of the year, and the exhibition will remain available online for the foreseeable future. Like so many cultural institutions, the library has been compelled by the ongoing crisis to close its doors to the public for the present, but its resources, including paintings and engravings, as well as documents, remain safe, and accessible. They are not the kind of cultural property argued over in the courts of international law, but they are no less valuable. Without them, the role of art in this part of history would be forever obscured.

[1] Barnes, Alan, and Stephen Leach. “”Two Girls with Their Black Servant” by Joseph Wright of Derby (1734–1797) and the Slavery Debate.” The British Art Journal 17, no. 3 (2017): 51-54.

See also Washington and Lee University Museum’s Breaking the Chains: Ceramics and the Abolition Movement. https://exhibits-museums.omeka.wlu.edu/exhibits/show/breaking-the-chains/are-these-objects-racist

Thomas Gainsborough, Portrait of Ignatius Sancho, 1768, National Gallery of Canada, public domain.

Thomas Gainsborough, Portrait of Ignatius Sancho, 1768, National Gallery of Canada, public domain.