An Interview by Andran Abramian

The loss of irreplaceable monuments and, indeed, of the whole history of Armenians in Nagorno-Karabagh/Artsakh, now partially under Azerbaijani control, is greatly feared by millions of people of Armenian heritage. That fear is based on the reality of past acts of destruction by the Azerbaijani government of thousands of medieval Armenian monuments, especially in Nakhichevan.

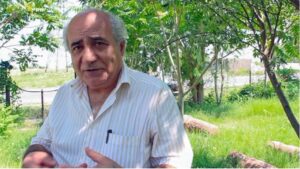

Argam Ayvazyan in Nor Kharberd with ram-shaped tombstones in the background. Courtesy Andran Abramian.

Cultural Property News is privileged to publish a rare interview with Argam Ayvazyan, a researcher who underwent many risks to secretly document the history and monuments of the Armenian people in the Nakhichevan. The interviewer, Andran Abramian, is a documentary filmmaker who graduated from FAMU film academy in Prague. Abramian’s work focuses primarily on topics related to nature, psychology, society and ideologies. The Argam Ayvazyan interview is a part of a project in progress dealing with the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict. Abramian and Ayvazyan spoke most recently in December 2020.

Geographically, Nakhichevan is an exclave belonging politically to Azerbaijan but separated from the bulk of the country by a section of Armenia. Nakhichevan borders both Turkey and Iran. The best-known case of systematic destruction of Armenian heritage at the medieval cemetery of Julfa (also called Djulfa of Jugha) was actually witnessed and filmed from across the border in Iran.

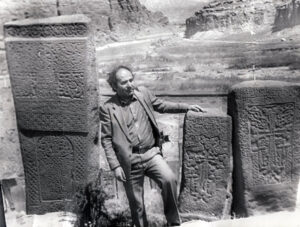

In his surveys in the Nakhichevan region of Azerbaijan between 1964 and 1987, Argam Ayvazyan personally recorded 89 standing churches and cathedrals that now no longer exist. He counted and documented 5,840 elaborate khachkars (cross-stones) and estimates some 22,000 flat tombstones which are now smashed, plowed under or removed. Eyewitness accounts – supported by statements in an Encyclopedia issued by Azerbaijani authorities – report that every remaining monument was destroyed by 2008 in the state sponsored campaign to eliminate Armenian history in the region.

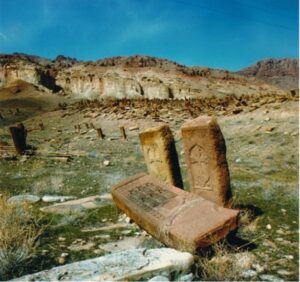

Argam Ayvazyan with khachkars at Julfa in 1971. Courtesy Argam Ayvazyan.

Argam Ayvazyan (born 1947, Arinj, Nakhichevan) is an Armenologist, cultural historian and author of more than 300 articles and 55 books, 48 of which deal with the material and cultural heritage of Nakhichevan. On November 2-19, 2007, an exhibition of Argam Ayvazyan’s photographs of Nakhichevan monuments was held at Harvard University, displaying over 250 pictures. He worked in the Monument Protection Department of Armenian SSR, in the Art Institute and Institute of Archeology and Ethnography of the National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Armenia. Today, he is a senior researcher at the Institute of Archeology and Ethnography.

THE LAST JOURNEY TO THE HOMELAND – FRIENDLY ENCOUNTERS AND A NARROW ESCAPE

When was the last time you visited Nakhichevan?

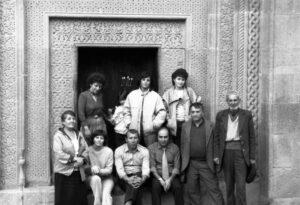

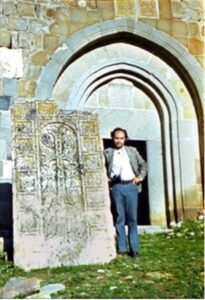

With friends and local Armenians during his last visit to Nakhichevan in 1987. This is the entrance of the 12-17th C. Holy Mother of God church in Tsghna (Çənnəb). The grandparents of the famous Armenian composer Komitas came from the village. Courtesy Argam Ayvazyan.

It was the end of October 1987. At that time I worked at the Monument Protection Department of Armenia. My female colleagues wanted very much to visit Nakhichevan and asked me if I could arrange a trip. So I asked the head of our department, who gave us his consent to go for a business trip to Meghri, in south Armenia. At that time, the road from Yerevan to Meghri passed through the territory of Nakhichevan. But he warned us to be careful, as the Karabakh movement[1] was already emerging at that time. We took our department’s van. We visited the city of Nakhichevan, where we saw the magnificent Seljuq tomb of Momine Khatun[2] and the Armenian Church of St. George. Then we went to Abrakunis, where we took photos at St. Karapet Monastery[3] and continued to Tsghna, a famous settlement of Goght’n region[4]. We arrived there in the late afternoon and by chance we met one of my old friends, Martin, who lived in Yerevan, and he wouldn’t let us go. In an hour, Martin set up a sumptuous table on the large balcony of his father’s 18th century two-story house. He hosted us with barbecue, village crops, homemade spirits… Ten other people from Tsghna gathered around the table and our party went on until 3 o’clock in the morning.

Did you ever get to Meghri [in Armenia] then?

Yes, we reached Meghri at dawn. After staying there for two days, we planned to visit the town of Agulis on the way back. As we entered Agulis[5] and parked the car at one of the Armenian cemeteries, I was completely stunned. The cemetery, which had held about 300 tombstones, was gone. A building had already been built in its place.

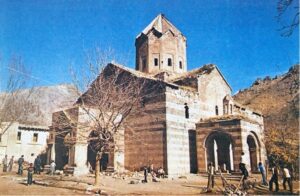

St. Thomas church, 4th-17th C., Upper Agulis (Yuxarı Əylis). Photo by Zaven Sargsyan, 1985. Courtesy Argam Ayvazyan.

In less than five minutes, twenty or thirty [Azerbaijani] people gathered around us and started asking questions. Of course, they did not believe my explanations and I could hear them telling each other “Let’s go get gas and burn the car.” I ordered the girls to get in the car. They said, “How come? Why can’t we see the wonderful place and go later?” At my urging, we all got in the van and drove off. The mob started throwing stones and sticks at us and followed us with their cars all the way to the highway. I explained in the car what the people who surrounded us were saying and what could have happened to us. We might not have got out of the village alive.

I also planned to visit Julfa on the way back to retake pictures of 200 khachkars that I had photographed a year before, but the KGB had confiscated the films. In Julfa we visited the house of my old acquaintance, Mrs. Mariam, an elderly Armenian who lived there alone. By the time we set up the table to eat, the autumn weather changed; fog-like clouds accumulated and that’s why I didn’t try to enter the Julfa cemetery. I thought I would come and take the pictures next spring, when the weather would be better. Unfortunately, it was a fatal mistake. After the Karabakh movement started in February 1988, it became clear that it would no longer be possible to return there.

YOUTHFUL PASSION: IDENTITY AND BELONGING

Detail of a Julfa khachkar. Courtesy Argam Ayvazyan.

For more than 50 years, you have been studying Armenian culture of your native Nakhichevan. After graduating from school, you moved to Yerevan, where you were admitted to the Faculty of Journalism, and then you became interested in this topic. How did it come about?

In 1964, when I was a first year student at the university, my classmates and I were once sitting around a table and enjoying wine at a restaurant in Yerevan. One of the boys said that we, as future journalists, might get an assignment to write an article about our birthplace. What would we write about then? I was thinking about what I knew about Nakhichevan and I only knew one or two names: Komitas’ grandparents lived there [the great Armenian composer Soghomon Soghomonian, who was ordained as Komitas], Aram Khachaturian [a major Soviet composer whose peasant parents were from Nakhichevan] and almost nothing else. That day, under the influence of wine, I did not go home and wandered through the streets of Yerevan all night, wondering how someone could know so little about his birthplace or history in general.

Argam Ayvazyan in 1973, at the 13th C. St. Trinity church in Nors (Nursu), where he was arrested for the first time in 1965. Courtesy Argam Ayvazyan.

I didn’t go to the lectures the next day. The National Library, the library of the Academy of Sciences and the Matenadaran [the Mesrop Mashtots Institute of Ancient Manuscripts[6]] became my university instead. During the years of Soviet rule, almost not a single line was written about the history and culture of Nakhichevan. Most of the Nakhichevan-related literature was limited to late 19th century works. Because I didn’t know exactly what to look for in the libraries, I ordered all the Armenian-related literature and went through it from top to bottom for about two years. This enriched my knowledge and only after that I started going to Nakhichevan and doing my research on the ground.

So, it was basically your private, personal project. Wasn’t there any official collaboration between Armenian and Azerbaijani scholars?

No, there wasn’t. Some researchers from the Armenian Academy of Sciences wanted to establish an official collaboration, but they never succeeded. Azerbaijan created various obstacles every time it was tried. Only once did Armenian and Azerbaijani scientists work together, in researching stone carved inscriptions in Nagorno-Karabakh.

MEETING THE FUTURE PRESIDENT OF AZERBAIJAN

When did you first realize that your job would not be so easy?

It was in 1965. I bought a very cheap camera and went from my native village of Arinj to the nearby village of Nors. Alone, with the camera hanging on my shoulder, I was openly photographing the church, the inscriptions, and the khachkars. The [Azerbaijani] villagers gathered and started asking who I was, what I was doing there and so on. I told them I was from a nearby village and was taking pictures just for my own interest. Coincidentally, there were two policemen in the village that day. They were immediately informed and I was arrested and taken to the regional police station.

We were waiting in the corridor and some time later, the chief officer went out of his office with a tall man in civilian clothes. The latter immediately asked the policemen, “What did this boy do? Did he steal something?” They said, “No, comrade Aliyev, we brought him from the Nors village, he was taking pictures of the church.” “Then bring him in.” I was taken inside, we sat down, they brought tea… He started asking questions about why I was taking the pictures (we spoke in Azerbaijani). The man took the camera, removed the film, threw it aside and said:

“This was the first time. Go and don’t do such a thing again. Forget there are any Armenian monuments or Armenians in Nakhichevan.”

That was Heydar Aliyev, the head of the KGB in Nakhichevan, of whom, of course, I didn’t know at the time. [Heydar Aliev became first secretary of the Azerbaijani Soviet Republic, then president of independent Azerbaijan. He is the father of today’s president of Azerbaijan, Ilham Aliyev]. This was my first encounter with the law. After that I realized that what I was going to do would not be easy; it turned out to be really quite difficult.

INTO FORBIDDEN NAKHICHEVAN

Map of Nakhichevan autonomous republic (Azerbaijan) with Soviet Administrative borders.

What kind of obstacles did you encounter?

The first obstacle was getting entry to Nakhichevan, which was possible only with special permission. During the Soviet era, the whole territory of Nakhichevan was declared a border zone. You had to have an invitation letter from there, saying that you are invited to visit your relatives or attend an occasion like a wedding, a funeral, and so on. Permission was granted only for three to five days, ten days at most. Basically, it was a visa system and it had very strict rules. The passport was granted only for a visit to a single place. If for any reason you wanted to go somewhere else, you had to inform the local authorities where you were going, for how many hours and when you would return. If they allowed it, you could go. If not, then you couldn’t leave your original destination for another place.

What did you have to be aware of after getting the permission?

If you hung around a monument for only three or four minutes, the locals would immediately gather, make inquiries, call the police. Then there could be arrests, interrogations, and fines. Camera confiscations would happen. After the first incident in Nors, I always hid my camera in handbags. At each monument, I decided the angle of the photograph, took a few quick pictures and then left. If there was another monument in the neighboring village, I wouldn’t go there. If they saw me in the first village, I’d say I had come just to go there. Had they seen me in the next village, they would immediately suspect that it was not a coincidence, but a planned visit. So after visiting a village, I would go to another region.

I suppose you did not inform the local authorities that you were going to another region.

Of course not. I also worked mainly on weekends when government offices were closed. True, the police worked, but the KGB didn’t. This helped so that I wouldn’t be reported right away.

You were already publishing your books during the Soviet years. You must have been a well-known person to the KGB in Nakhichevan. How did you bypass them?

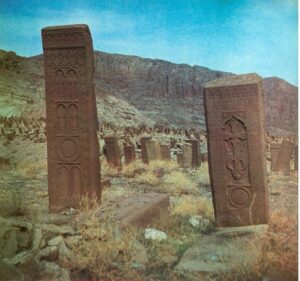

View of the Old Julfa cemetery, prior to its complete destruction. Courtesy Argam Ayvazyan.

They already knew my name in 1978-1981, when I had published my first books. They even distributed my photo and instructed local authorities to arrest me if they found me on a visit. I had to make fake documents with different names. Of course, I showed those only to ordinary villagers. I couldn’t show them to government officials, because they could easily find out that they were false.

There were also other ways to enter Nakhichevan. Nakhichevan Armenians who lived in Armenia sometimes went on a pilgrimage, or they just visited their native villages without any permission. A group of them would hire a bus and bypass the checkpoint at night. I often went with these groups as a pilgrim or as a fellow villager. I mentioned in one of my books that my work in Nakhichevan could have been compared to a spy’s job.

DOCUMENTING JULFA’S THOUSANDS OF KHACHKARS

View of the Old Julfa cemetery, prior to its complete destruction. Courtesy Argam Ayvazyan.

At some places, it was possible to photograph the monuments during a short visit, without causing much suspicion. But there were other places where you had to return repeatedly in order to document them, namely the Old Julfa cemetery. There were more than 2700 khachkars (4500 including the churchyards in Old Julfa) and moreover, it was located right on the Iran-USSR state border. How did you manage to get there?

Access to Julfa was forbidden even for the locals. I managed to find ‘common ground’ with the Russian military border guards and their chiefs, by giving them bribes for instance. Each time I was there, I was accompanied by two or three border guards and was permitted to enter the place only for two or two and a half hours. I visited the ancient Julfa cemetery sixteen or seventeen times in order to document it.

How did you remember where you had finished your work the last time?

I had a 50-60 meter long thin thread with me. I tied it along a row of khachkars so that I wouldn’t confuse them; they were very close to each other. And I also made a special mark on some of them with white paint. It happened that I photographed some khachkars over again. It is very likely that I missed some. Anything is possible, because having just two hours to take all those pictures was not an easy task. I used several cameras, with black and white film, slides, large format, narrow format. Naturally, 36 shots would be used up immediately. I had to often change the film. Once, the KGB arrested me on the spot and confiscated six canisters of negatives.

How did they find out you were there?

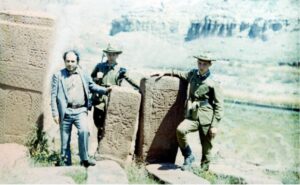

Argam Ayvazyan with Russian border guards at Old Julfa cemetery. Courtesy Argam Ayvazyan.

A small freight train passed by. I suppose the train drivers noticed that I was taking pictures and they informed the police in Julfa, which was only four kilometers away. They came and caught me in ten minutes. They took me to the regional KGB office in Julfa, interrogated me, kept in a dirty basement for a day or two… If an official record was made, I wouldn’t be able to get permission to visit Nakhichevan anymore. Finally, I was able to ‘find a common ground’ with them, bribed them and freed myself from the threatened ‘accountability’.

ON PILGRIMAGE WITH A ROOSTER

Apart from Julfa, one of Nakhichevan’s richest villages in terms of Armenian monuments was Agulis with its twelve churches. In one of your books there is a photo of the 4th – 17th century St. Thomas church in the Upper Agulis. We can see quite a lot of people around it. How did you work in such populous places?

Frescoes in St. Thomas church, Upper Agulis (Yuxarı Əylis), created by the Armenian poet and painter Naghash Hovnatan in the 1680s. Courtesy Argam Ayvazyan.

St. Thomas church stood right inside the village. It was impossible to take photos there without getting noticed. Therefore I used a trick during one of my seven or eight visits to Agulis. I knew some women from the village of Der. One of them was an elderly lady named Marus whom I had visited several times. So I went to Agulis with Marus, another local woman and her granddaughter. I took a rooster with me and pretended to be mentally ill. We approached the St. Thomas’ church. Marus explained to the women, men, and children, who had gathered around us, that this guy had been told to walk three times around the church with that rooster, then go inside and pray alone in order to get healed. We managed to convince them, they brought the key, opened the door, and I entered. I had told Marus in advance not to let anyone in. That’s how I was able to photograph the frescoes created by Naghash Hovnatan and measure the plan of the church.

Location of St. Thomas church in Agulis indicated by a cross on a Soviet military map and a satellite image showing the new mosque built in its place. Courtesy Argam Ayvazyan.

After we had already visited and photographed several monuments in Agulis, we were heading to St. John’s Church and noticed a police car approaching. The Azerbaijanis actually hadn’t really believed us and had called the regional police station in Ordubad. To be sure they weren’t found, I had already given all the negatives to the women. The police car indeed stopped us. They came and asked questions. Marus told them we went on a pilgrimage, for I was ill. Meanwhile, I was doing weird movements with my head and my hands. Seeing me, the two officers said, “Yes, this boy seems to be ill,” and they left.

The late researcher Samvel Karapetyan, who photographed and documented many Armenian monuments (not only) in Azerbaijan, told that he always got acquainted with the Armenian inhabitants in the villages, who accompanied him, provided a place to sleep, etc. Was your method the same?

Argam Ayvazyan with a group of pilgrims at the ruins of the 14the-17th C. St. Stephen monastery in Poradasht near Shurut. Courtesy Argam Ayvazyan.

Yes, it was similar. But it was a little different compared to other regions in Azerbaijan. Nakhichevan was being emptied of Armenians and local authorities tried to ensure that nothing was published about their history, monuments or culture. Even in Turkey, it was easier to approach Armenian monuments than in Nakhichevan. The local Armenian population was told not to help people coming from Armenia, specialists or not, and to report those who came and what they did.

There were cases that after my visit to a village, Azerbaijanis summoned the Armenians for interrogation, put pressure on them and so on. They even interrogated the Russian border guards and commanders in Julfa. I knew that if the Azerbaijanis found out that an Armenian from Yerevan had come to someone’s house, they would have bothered the people. So I told very little information to the Armenian families I met. I was saying things like “my grandparents came from that village, I’d like to see the cemetery, the monuments…” People often didn’t know who I was and why I really came there.

FACTORS DRIVING THE ARMENIAN POPULATION OUT OF NAKHICHEVAN

Many villages had already lost their Armenian population by the late 1980s. What were the reasons for this decline?

The Holy Mother of God church in Tsghna (Çənnəb) in the 1980s and the same view in 2014. Courtesy Argam Ayvazyan.

After the twenties, when Nakhichevan became part of Soviet Azerbaijan, ties with the Armenian state and its culture were severed. After WWII and along with the repatriation of Armenians from the diaspora in 1947, a significant part of Nakhichevan Armenians moved to Armenia too and Armenian authorities did nothing at that time to prevent them from doing so.

Then there was a matter of language. The state language was Azerbaijani, so Armenians who had graduated from an Armenian-language school couldn’t get a state job. They would have to work as laborers or collective farmers. After graduating from school, the youth moved to Armenia and the elders remained. Armenian schools were being gradually closed and when the elders died, the villages slowly perished.

In the Soviet Union, there was also the system of appointing young graduates to a job. In an Armenian village, the chairman of the collective farm, or the livestock specialist, the agronomist and others did not have [Azerbaijani] higher education. An Azerbaijani graduate would then be appointed to work there as an agronomist, for instance. He would move in with his family. Then their relatives would come. Armenians were dismissed from their posts and the village would slowly become half-Azerbaijani. The government was deliberately pursuing this policy. In general, the Armenians in Nakhichevan were cut off from Armenian social and cultural life during the Soviet era, so it was very difficult.

Do you think the population of Armenians in Nakhichevan would have dropped so much if they had known the Azerbaijani language?

No, I don’t think it was a key factor. There were Armenians who knew Azerbaijani. Some of them were even state officials, for example the Deputy Chairman of the Nakhichevan Council of Ministers, and the second or third secretaries of the Regional Committee, but they were always under pressure. They had to do what they were told. My father worked at the regional Statistics Department and, as an Armenian, was subjected to pressure and disregard.

Could you give an example?

For example, compared to his Azerbaijani colleagues, his pay was never raised or he was given the lowest quarterly bonus. He compiled the official statistical documents on the activities of Azerbaijani villages and collective farms. They forced him not to mention the existing shortcomings. There were various kinds of pressures. After more than twenty years of being a top specialist in his field, he was finally fired under the pretext of reduction.

ERASING ARMENIAN HERITAGE IN NAKHICHEVAN

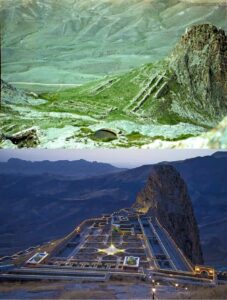

Julfa cemetery before its destruction in the 1990s and its cleared site turned into a shooting range in 2006. Courtesy Argam Ayvazyan.

How did the local Azerbaijanis treat the Armenian monuments?

It must be said that the ordinary, common people didn’t really destroy them. They had quite a respectful attitude to God-related monuments. Of course, there were some cases of damage done by treasure hunters, for instance. Some old Armenian valuables were also destroyed during the development of villages or towns, but basically 90% remained unattended and without repairs. However, in 1997-98, a state program was launched across the territory of Nakhichevan to destroy the whole of Armenian heritage there.

As a result, about 27,000 objects of cultural heritage – churches, khachkars, monuments, gravestones etc., were completely annihilated between 1998 and 2006. Especially during the last decade, mosques have been built on the sites of churches, and secular monuments, such as fortresses and bridges, have been carelessly ‘restored’, being given a distorted new appearance and turned into Azeri shrines and monuments. This is a huge loss, a cultural genocide. Sadly, no Armenian monuments exist in the Nakhichevan area today. All of them remain only in the pages of my books.

Wasn’t there an effort to prevent it?

The Julfa cemetery was an unparalleled repository of Armenian khachkar art. The footage of the destruction of the Julfa cemetery, which frequently circulates on the Internet, shows the last stage of the destruction. The first stage, which started in 1998, was held up after Armenia raised some complaints. Then they restarted it two years later, Armenia complained again, they stopped again, and this repeated three or four times. So we basically didn’t manage to go beyond complaints to do what we could to save even the famous Julfa cemetery. It was utterly erased in December 2005․ They smashed the 13th -17th centuries khachkars into rubble and dumped the pieces into the Arax river. The vast area of the cemetery was flattened and turned into a military shooting range in 2006.

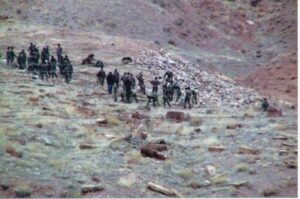

Azerbaijani servicemen destroying the Julfa cemetery in December 2005. Courtesy Argam Ayvazyan.

Unfortunately, neither Armenia nor leading humanitarian or scientific organizations in the world were able to stop this vandalism by Azerbaijan. Now, after destroying all the examples of Armenian heritage, Azerbaijan has repeatedly stated to the world that there were never any Armenian monuments in the territory of Nakhichevan whatsoever.

After all this, about thirty khachkars and ram-shaped tombstones from the Julfa cemetery have survived. They were moved to Armenia and other countries at various times during the 20th century. Six tombstones are also located in Nor Kharberd, Yerevan. How did they get there?

A ram-shaped tombstone from Old Julfa at Hazaraprkich sanctuary in Nor Kharberd, Yerevan. Courtesy Andran Abramian.

They are at the ‘Hazaraprkich’ [Savior of the Thousands] sanctuary founded by Nakhichevan Armenians (also under my active leadership). We gather there in large numbers every year on the second Sunday of October, on the Day of the Savior, and celebrate the feast. During the Soviet years, the Armenians from Julfa had contacts with the Russian border guards, who gave them permission to take those tombstones. Therefore, in 1996, I suggested displaying these Julfa valuables there. I also brought one of the tombstones to the State Museum of History of Armenia. It is now on permanent display.

Foundations of the 7th century Yernjak (Əlincə) fortress in 1970s and its ‘brand new’ look today. Courtesy Argam Ayvazyan.

FUTURE OF ARMENIAN HERITAGE IN NAGORNO-KARABAKH?

After the recent war, there arose many concerns about the fate of Armenian monuments in Nagorno-Karabakh. The case of Nakhichevan is often mentioned in this context. What do you think are the future scenarios for the Armenian monuments in Karabakh? What lesson can Armenia learn from the Nakhichevan case this time?

Unfortunately, Armenia at the state level, as well as Armenians in general have not learnt any lesson and raised a sufficient protest in the past. In the last few months, different kinds of small monuments have been already smashed in Karabakh settlements that came under Azerbaijani control. Recently, the president of the Union of Architects of Azerbaijan expressed himself that the Armenian churches should be eliminated in the areas under their control.[7] Since Armenia has recently raised more urgent issues and complaints to UNESCO regarding the preservation of the monuments, perhaps they will be able to curb Azerbaijan’s attempts at vandalism to some extent. However, if these territories remain under the control of Azerbaijan, I believe that 90% of the Armenian monuments there will be destroyed during the next decade. The Azerbaijanis will give various reasons for the destruction. Then Azerbaijan will announce that there have never been any such monuments. Some of the churches will be certainly kept as ‘Caucasian Albanian’, as they have been promoting this false, pseudo-scientific notion that the monuments in Karabakh have nothing to do with Armenians.[8]

President of Azerbaijan, Ilham Aliev, during his visit to Nagorno-Karabakh in March 2021. He is

pointing at the Armenian inscription on the tympanum of a 12-17th century church in Tsakuri/Hunerli village and calling it fake. He also calls the church “our ancient historical monument“ and promises to restore the “ancient Albanian temple.” This means erasing the Armenian inscriptions, which has been already done during a number of church “restorations” in Azerbaijan. The oldest inscription from this church is on a khachkar mentioning the year 1198 (ՈԽԷ in Armenian numerals). The inscription on the tympanum says “…I [Vardapet (abbot) Hakob] reconstructed the former church… in 1682.”

[2] The Momine Khatun Mausoleum, an elaborately patterned brick construction of the Seljuk period, stands 36 meters high. The resting place of local Muslim ruler’s wife was built in the west part of Nakhichevan city in 1186.

[3] St. Karapet Monastery (Surb Karapet of Abrakunis) was a medieval Armenian monastic complex that functioned for centuries as a school and a repository for ancient manuscripts. The monastery was demolished by 2005, when a Scottish traveler found a razed ground on its place. A mosque was built on the site in 2013. https://www.djulfa.com/nakhichevan-2005-the-state-of-armenian-monuments/

[4] The easternmost region of Nakhichevan. In the Armenian tradition, Goght’n region was most famous for its rich historical heritage and cultural life as well as fine fruits and wine making.

[5] Agulis, once a local center of Armenian culture, with twelve churches and monasteries. A violent pogrom took place there in December 24-25, 1919, perpetrated by the Turkish army and Azerbaijanis who had been driven from nearby Zangezur. In the attack on the Armenian population of Agulis, some 1400 people were killed. Agulis’ monuments, though neglected, remained intact until about 1988, when Ayvazyan documented the destruction of the cemeteries. Agulis is also the birthplace of Azerbaijani author Akram Aylisli, who has been persecuted by the regime for writing about pogroms and depicting Armenians in sympathetic light.

[6] The Mesrop Mashots Institute of Ancient Manuscripts in Yerevan, Armenia, popularly known as the Matenadaran, holds the world’s largest collection of ancient Armenian manuscripts. https://matenadaran.am/en/matenadaran/home/

[7] A recently built church was proven to be demolished in the territories under Azerbaijani control, which was subsequently denied by the state. https://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-europe-56517835

[8] ‘Albanization’ is the term for a 60-year-old popular distortion of the region’s history that has been promoted by the Azerbaijan government as part of its historical agenda. The claims that Armenians have no ancient history in the region is a means of both bolstering the nationalist propaganda that the region is an ‘ancient Azerbaijani land’ and denying modern Armenians the rights to their ancient cultural monuments.

Ayvazyan at the 12th-17th Century Church of St. Jacob (Hakob Hayrapet) in Paraka (Parağa),

and the location of the now-demolished church in a satellite image. Courtesy Argam Ayvazyan.

Ayvazyan at the 12th-17th Century Church of St. Jacob (Hakob Hayrapet) in Paraka (Parağa),

and the location of the now-demolished church in a satellite image. Courtesy Argam Ayvazyan.