The cases Ancient Coin Collectors Guild v. U.S. Customs and Border Protection and U.S. v. 3 Knife-Shaped Coins etc., involving fifteen coins from China and Cyprus, none very beautiful or valuable, began as a test case in 2009, and has been hard-fought at every step by the nonprofit Ancient Coin Collectors Guild (ACCG). An important goal of the test case was to challenge the U.S. State Department’s actions in going far beyond the definitions and requirements set by Congress for import restrictions under the U.S.’s only deliberately crafted and comprehensive international cultural property legislation, the Convention on Cultural Property Implementation Act (CPIA).

Peter K. Tompa, of Bailey & Ehrenberg PLLC, Washington, D.C., lead attorney in the ACCG test case.

The lengthy legal battle has been possible only through the ACCG Board’s commitment to requiring adherence to law in the administration of U.S. cultural property policy. ACCG lead attorney Peter K. Tompa has shown unflagging determination to preserve Congress’s intent in the express language in the statute and to renew the integrity of the review process under the CPIA. The Guild has been equally tireless in pursuit of the public’s interest in due process under the Constitution. A host of amici added their voices (the Committee for Cultural Policy, the publisher of Cultural Property News, was one). Amici included the American Numismatic Association, Professional Numismatists Guild, International Association of Professional Numismatists, Association of Dealers and Collectors of Ancient and Ethnographic Art, and Global Heritage Alliance.

The result, after years of litigation, is that the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit has affirmed U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s original seizure of the coins, and also re-interpreted the plain language of the CPIA, by promoting ease of enforcement over due process and the legal requirements in the original legislation. In so doing, the Court did not criticize misrepresentations by the State Department to Congress, or its failure to follow the statute’s fundamental principles of balanced review. Finally, the ruling effectively lessens the government’s burden of proof to show that objects were unlawfully imported, a consequence Congress sought to avoid in the original legislation.

The remaining option for the ACCG will be to file a Petition for Writ of Certiorari asking the Supreme Court to review the decision of the lower court. Wayne Sayles, the Ancient Coin Collectors Guild’s founder, explained the reasons for ACCG’s added efforts. “When Congress enacted CCPIA in 1983 they mandated the criteria for imposition of import restrictions on cultural property. The Court needs to confirm that clear mandate and serve the cause of justice through rule of law. We hope to give them that opportunity.” Peter Tompa, the ACCG’s executive director (and a CCP Board Member), added, “Fighting to keep the burden of proof on the government where it belongs under the Statute and our Constitutional notions of a presumption of innocence are worth the effort, even if the Court only decides to conduct a review of 1-2% of the petitions put before it.”

The decision in the case

Image of a Cypriotic coin from the reign of Caracalla (2nd/3rd century A.D). Depicting the temple of Aphrodite at Paphos. The legend reads “KOINON CYPRION” (confederation of cypriots). An illustration from the Encyclopaedia Biblica, 1903 publication, public domain.

In the litigation, the Guild had argued that under the CPIA, import restrictions may only be applied prospectively to illicit exports of objects “found in” and subject to export controls in a particular country after they have been “designated” for restrictions.

The lawsuit also provided information that called into question whether the original decision to impose import restrictions on historical coins was made in good faith. In particular, in reaching its decision, the Fourth Circuit simply ignored statements under oath by two Cultural Property Advisory Committee Members, past Chairman Jay Kislak and Robert Korver, a trade representative. Their declarations stated that the State Department rejected CPAC’s recommendations on coins and then misled the public and Congress about it in official government reports. Korver added that after CPAC failed to go along with import restrictions on Cypriot coins, CPAC was precluded from deliberating on whether there should be import restrictions on Chinese ones.

Instead of questioning what actually happened inside the Committee’s secret deliberations, or how the State Department altered its recommendations and avoided Congressional reporting requirements, the Court emphasized how, at least on paper, the criteria in the law ensured balanced investigations, and that the Designated Lists created through this process would provide adequate notice and guidance to importers. The Court indicated that if changes were needed to the MOUs or to the Designated Lists, or to how the designated lists are implemented in forfeiture proceedings, then the ACCG should address them to Congress.

The Court was not disturbed that the Department of State had arrogated extraordinary authority to itself to overwrite the limitations of the law, even when it could also be shown that the administration had disregarded not only specific timeframes, place of finding, and other criteria to be met, but also ignored the recommendations of the Cultural Property Advisory Committee.

In reaching its decision, the Court also gave no weight to prior statements of State Department and Department of Justice attorneys that the government would have the burden of proof to show if a forfeiture was warranted on import.

How will this decision impact the future ability of collectors to import archaeological and ethnological objects?

The answer depends largely upon the integrity of the review process under the CPIA, both in the recommendations of the Cultural Property Advisory Committee and on ensuring that the State Department’s officials at the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs do not overstep their authority under the law. The decision curtails, at least for the moment, the ability of collectors and dealers to seek a correction to overbroad and unjustified import restrictions and unwarranted seizures by pointing out that the Designated Lists do not comport with the requirements under the CPIA, or that the process creating the existing lists was fundamentally flawed.

It means that until a future correction is made, neither Congressional intent, nor the criteria in the actual law, can set the limits of import restrictions, if the Department of State and the Cultural Property Advisory Committee fail to follow the Cultural Property Implementation Act as it is written.

How did this Court decision happen?

The 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property (the UNESCO Convention for short) contemplates that the nations that sign it will assist each other in enforcing export controls on cultural goods. The UNESCO Convention covers archaeological objects found on national territory, not archaeological objects that traveled in ancient times and are found on other nations’ lands. Further, the UNESCO Convention is not self-executing. Simply signing it does not create a domestic law or put in place import restrictions in each signatory nation.

The U.S. is one of the few nations that have actually implemented the UNESCO Convention into a domestic law, the CPIA. The CPIA enacted the UNESCO Convention subject to US independent making judgments about scope and need for import controls. The U.S. Congress was not willing to give foreign nations a blank check to determine what would be illegal to import into the U.S., especially those nations that did not respect private property rights as the U.S. does.

A foreign nation that is a signatory to the 1970 UNESCO Convention may request the U.S. to impose import restrictions on specific types or periods of objects forming part of its cultural property if these objects are in immediate jeopardy of looting, if the requesting country has taken self- help measures and if other nations which have signed UNESCO join the U.S. in a concerted international response.

The Cultural Property Advisory Committee is an advisory body under the aegis of the State Department that is supposed to represent the interests of different constituencies in the circulation of cultural property in the U.S. The Cultural Property Advisory Committee was set up to provide useful advice on whether to enter into cultural property agreements and what they would cover. The scope of import restrictions should reflect a balance between the need to halt looting, and recognition of both the benefits of an international circulation of art, and the fact that most objects in circulation were not unlawfully acquired.

Consistent with UNESCO, the CPIA only allows import restrictions on archaeological objects first discovered within and subject to the export control of a specific UNESCO State party. The statute is also prospective. Congress could have, but did not embargo entry of items found on a designated list that were imported before the effective date of regulations imposing import restrictions. Instead, the restrictions only apply to objects that are illicitly removed after the effective date of the regulations from the State Party.

A Designated List of objects subject to import restrictions is supposed to be created based upon the criteria in the law and the recommendations from the Cultural Property Advisory Committee. Actually, the final, detailed Designated Lists are now virtual laundry lists, compiled behind the scenes in discussions between the foreign nations, the State Department and U.S. Customs.

The CPIA in Practice

Mark B. Feldman, State Department negotiator during passage of the Cultural Property Implementation Act. His commentary, Reform of U.S. Cultural Property Policy, provides extraordinary insight into the original intent of the Act.

When the CPIA was being discussed, Mark Feldman, then a Department of State Deputy Legal Adviser, was the point person with Congress. In response to a question from a Trade Subcommittee chair, Feldman stated that it would be hard to imagine a case where there would be import restrictions on coins.

Separately, he also indicated this about the burden of proof:

“Now, if I may pass for a moment to the question of procedures and burdens of proof, which is the area of one of the great improvements in the bill…. The Government must show both that it [the artifact] fits in the proscribed category and that it comes from the country making the agreement. So the burden of proof of provenance is on the Government…. This means in a significant number of cases it will not be possible to require an object’s return. . . . .The only country that would have the right to claim such an object under the bill is the country where it was first discovered. It would have to be established that the object was removed from the country of origin after the date of the regulation.”

Statement of Deputy State Department Legal Adviser, Mark Feldman in Proceedings of the Panel on the U.S. Enabling Legislation of the UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property, 4 Syracuse J. Int’l L. & Com. 97 1976-1977 at 129-130.

Placing the burden of proof on the government gave importers the ability to contest seizures in court, and to require the government to prove that the objects were unlawfully exported.

At first, the U.S. placed import restrictions only on a limited universe of artifacts from mostly poor countries without well-funded customs services. Starting with a MOU with Italy in 2000, restrictions became far broader, covering almost all artifacts of a given culture. MOUs were also given to wealthy countries that could afford well-trained customs forces to police their borders. Gradually, more and more countries were granted import restrictions in the U.S. under the CPIA process. The restrictions not only became virtually all-encompassing; these “temporary” 5-year fixes to a looting problem were renewed again and again, so that some countries now have 30-year-long import restrictions.

In 2007, import restrictions were extended to Cypriot coins. This was done contrary to the recommendation of the CPAC and despite the well-known facts that such coins traveled widely, by the many thousands in the ancient world, and are found today in many countries. Before that, CPAC had previously rejected import restrictions on both Cypriot and Italian coins, and the State Department had honored CPAC’s recommendations.

The Ancient Coin Collectors Guild (ACCG) is an advocacy group for ancient coin collectors formed in 2004. Based on Freedom of Information Act releases and consultations with CPAC members, ACCG learned that the State Department had rejected CPAC’s recommendations against including coins and then misled Congress and the public about it in official government reports. That prompted ACCG to seek judicial review of the decision to impose import restrictions.

Initial Litigation

Cypriot and Chinese coins. Courtesy ACCG.

Federal courts will only address live cases or controversies. So, the ACCG had to import coins in order to have a court undertake a judicial review of the decision to impose import restrictions on coins.

By the time ACCG was ready to do so, the “Cypriot precedent” of including coins on a Designated List was used as a basis to impose import restrictions on Chinese coins, including incredibly common “cash coins” that circulated widely not only in China, but all over the Far East and parts of Africa. So the ACCG also decided to import Chinese coins for purposes of its test case.

Spink, a well-known UK numismatic firm that dates back to 1666, kindly agreed to help ACCG to locate coins for the test case. The Cypriot coins that were to be imported evidently had been stored in boxes at Spink for some time. As Spink did not have any Chinese coins, these were sourced from a Canadian dealer.

Although the ACCG’s attorney’s firm was located in Washington, DC, the coins could not be imported there as there is no “port” for customs purposes. This was unfortunate as the DC Circuit Court has handled many cases involving reviews of agency action, and is considered the premier judicial circuit in that regard. As an alternative, the coins were imported into Baltimore, through BWI International Airport.

The Cypriot and Chinese coins had no solid provenance, a traceable history of ownership or place of origin, which is typical of coins on the market. The commercial invoice that accompanied the coins reflected the seller’s lack of knowledge about the coins’ provenance. While the invoice identified the coins as being minted in either Cyprus or China, it also indicated that each had “No recorded provenance. Find spot unknown.”

On their arrival in Baltimore in April 2009, the coins were first detained and seized, but then the government sat on them. Ultimately, after waiting almost a year for the government to act, the ACCG decided to bring its own action in U.S. District Court in Baltimore. The case was assigned to the Hon. Catherine Blake, who had formally been the acting head of the U.S. Attorney’s office, which was given the job of defending the case.

The ACCG sought judicial review under the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) and the doctrine of “ultra vires” review. (“Ultra vires” is a Latin phrase meaning “beyond the power.” If an act requires legal authority and it is done with such authority, it is characterized in law as intra vires, “within the powers.” If it is done without such authority, it is ultra vires.) Thus, the ACCG alleged that the Department of State and U.S. Customs and Border Protection had acted beyond their legal authority to place import restrictions on the coins through Designated Lists.

The ACCG asked the Court to consider whether it was proper to impose import restrictions based on where coins were manufactured as opposed to where they were found. The criteria required for their listing under the CPIA is where they were found.

The ACCG also asked the Court to consider whether there was a concerted international response creating similar import restrictions in other countries, also as required under the CPIA.

This is necessary for restrictions under the CPIA, and is especially relevant given the fact that such coins are widely collected, including inside China and Cyprus. The Guild also pointed out procedural irregularities with the decision to impose import restrictions, most notably that CPAC recommended against restrictions on Cypriot coins, but the State Department then misled the Congress and public about these recommendations in official government reports.

While the District Court agreed with the Guild that import restrictions can only apply to archaeological objects first discovered within Cyprus and China and hence be subject to their export controls, the District Court refused to undertake the judicial review the Guild wanted and instead dismissed the Guild’s case.

In so doing, the Court said that there could be no Administrative Procedure Act review of Agency Action because the decision to impose import restrictions was delegated from the President, who is not an Agency. The Court also rejected the Guild’s argument that the “final agency action” for which review was sought was not the decision made by the person who was delegated the President’s decision-making authority in the State Department, but the decisions made by U.S. Customs, which was responsible for drafting import restrictions.

The Court also said the government acted properly under a very narrow version of ultra vires review which looks at whether the government exceeded its delegated authority. The Guild had wanted the Court to apply a version of ultra vires review where the Court would construe the CPIA as a contract, whose terms and requirements would have to be met for objects to be added to a Designated List.

Although the Appeals Court also recognized that the Government was only entitled to restrict articles of “archaeological interest” “first discovered within” and “subject to export control” by the specific UNESCO State party, the Court held that anything but the most cursory review of the State Department’s procedural compliance with the CPIA, based largely on the Government’s own recitation of that process found in the Federal Register, “would draw the judicial system too heavily and intimately into negotiations between the Department of State and foreign countries.” The Appeals Court then affirmed the District Court’s decision, but only predicated on the assumption that “the basics of due process require that the Guild be given a chance to contest the Government’s detention of its property” in a timely forfeiture action.

The Forfeiture Action and Present Appeal

On April 22, 2013, the Government finally brought a forfeiture action. The Government never contended the Guild’s coins were “looted” or “smuggled.” The ACCG then filed a verified claim of interest in the property and an answer to the forfeiture complaint. Instead of requiring the government to respond to written discovery, the Court allowed the government to file a motion to strike the Guild’s Answer and Affirmative Defenses. Relying heavily on ACCG v. CBP, the District Court held that the Government made out its prima facie case in its forfeiture complaint. (When a cause of action or defense is sufficiently established by a party’s evidence to justify a verdict in his or her favor, provided such evidence is not rebutted by the other party, that is called making a prima facie case.)

The Court then struck the Guild’s entire Amended Answer on its own initiative, and precluded any meaningful discovery of information between the parties before forfeiting fifteen of the Guild’s coins to the Government.

An appeal followed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. The Guild’s appeal focused on 5th Amendment Due Process issues arising out of the Government’s burden of proof in CPIA forfeiture actions as well as the Guild’s required showing on rebuttal. Those issues relating to the Government’s burden of proof were the most important.

The Guild has consistently maintained that the Government must establish for its prima facie case that an archaeological object: (1) is of a type that appears on the designated list; (2) that was first discovered within and hence was subject to the export control of the UNESCO State Party for which restrictions were granted; and (3) that it was illegally removed from the State Party after those restrictions were granted.

The Guild based its analysis on the rules of statutory construction (including the “rule of lenity”), CPIA and other civil forfeiture case law, a statement about the burden of proof Mr. Feldman made as State’s CPIA point person, and Government admissions about the burden of proof and use of expert testimony made in the Declaratory Judgment action.

The Guild also argued that the District Court could not assume that the Government made out the second and third elements of its prima facie case solely based on the presumption these determinations were made as part of the process of “designating” like types of archaeological objects for restrictions.

- First, Fifth Amendment due process precludes altering the burden of proof Congress assigned to the Government to the Guild’s detriment.

- Second, due process also precludes seizure and forfeiture based on regulations and guidance that contradict the CPIA.

- Finally, the Guild argued that ACCG v. CBP was dicta for purposes of construing the burden of proof in a CPIA forfeiture action under 19 U.S.C. § 2610, and, in any case, the constitutional claims at issue also meant that the decision was not binding.

Given this constitutional context, the Guild argued the District Court should have considered sworn testimony from former CPAC members and additional information that demonstrated that the Appeals Court in the Declaratory Judgment action made demonstrably erroneous factual assumptions about Government decision-making that impacted its decision.

Wayne G. Sales, former President of ACCG. “When Congress enacted CCPIA in 1983 they mandated the criteria for imposition of import restrictions on cultural property. The Court needs to confirm that clear mandate and serve the cause of justice through rule of law. We hope to give them that opportunity.”

The Guild provided evidence including declarations from CPAC members that CPAC had not approved import restrictions on Cypriot coins, and that the Committee was not allowed to make any recommendation on Chinese coins. The Guild also developed evidence that the decision maker for Cypriot import restrictions, Ms. Dina Powell, had at least an appearance of conflict of interest when she approved import restrictions on Cypriot coins. At the time she approved the restrictions, she had already accepted a high paying job at Goldman Sachs, where she was recruited by and worked directly for the spouse of an Archaeological Institute of America Trustee who has been vocal in seeking expansive import restrictions on cultural goods, including coins.

The Guild also argued that the Court should have considered Mr. Feldman’s contemporaneous statement about the burden of proof in a CPIA forfeiture action as well as statements the Government made in the Declaratory Judgement action about the burden of proof.

The Panel rejected all the Guild’s arguments without fully addressing the Guild’s constitutional claims, prompting ACCG to request a rehearing. ACCG submitted that the ruling in ACCG v. CBP must be considered dicta, not binding precedent, for purposes of ruling on the burden of proof in a forfeiture proceeding where 5th Amendment due process rights are at stake. The ACCG wrote:

“In counsel’s judgment, (1) material factual and legal matters were overlooked; (2) the opinion conflicts with a decision of the U.S. Supreme Court, this court and other court of appeals, and the conflict was not addressed; and (3) the case involves questions of exceptional importance. The Panel’s decision collapses any meaningful distinctions among detentions, seizures and forfeitures and between ultra vires and constitutional review. Furthermore, it has effectively rewritten prospective, targeted CPIA import restrictions into embargoes on all archaeological objects of types found on designated lists. Amicus support attests to the public importance of these issues. Rehearing is warranted.”

U.S. v. Ancient Coin Collectors Guild, 17-1625, Claimant-Appellant’s Petition for Rehearing and Rehearing En Banc, 3

On October 5, 2018, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit denied the ACCG’s Motion for rehearing and rehearing en banc.

What does this all mean in practice?

Since the 4th District rejected rehearing the case, the decision—which is only binding in the 4th Circuit (Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia, South Carolina, North Carolina) will likely be cited elsewhere by the Government for the proposition that all it has to do is show that an item is of a type on a designated list for it to be seized and forfeited under the CPIA.

This should be particularly troubling because the increasing numbers and scope of MOUs to cover virtually everything, means that nothing will be importable unless it has proper documentation showing it was out of the country at the date of restrictions—something often hard to come by in practice, particularly for items of limited value like ancient coins.

It should also alarm all U.S. stakeholders in cultural property matters, from collectors to art dealers to museums, archaeologists, and academics, that the courts were so willing to gloss over the State Department’s failure to honor the careful balance that Congress built into the Cultural Property Implementation Act.

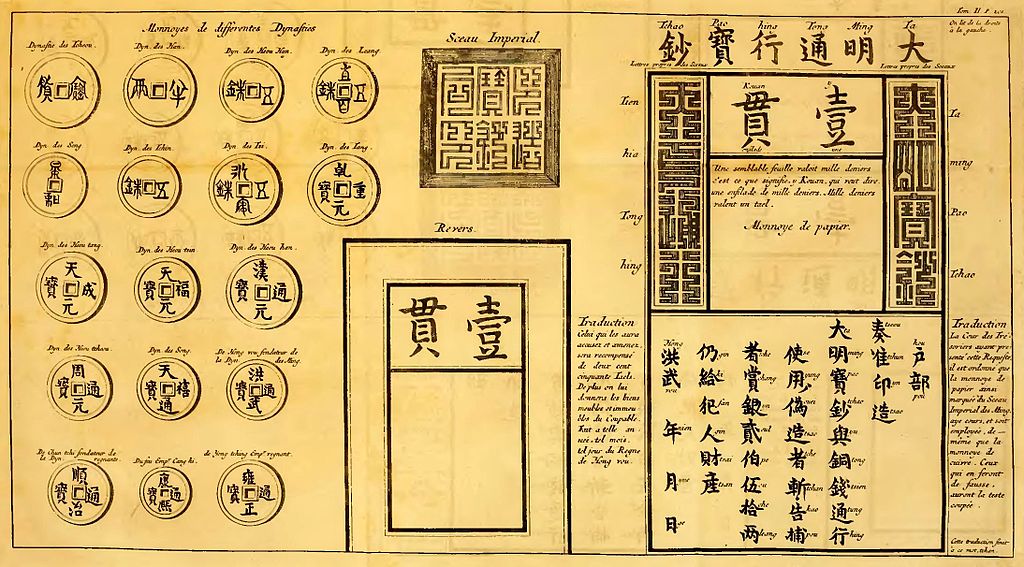

EngravingDescription de la Chine, édition de La Haye 1736. Volume 2. Page 201, Jean-Baptiste Du Halde, via Wikimedia Commons

EngravingDescription de la Chine, édition de La Haye 1736. Volume 2. Page 201, Jean-Baptiste Du Halde, via Wikimedia Commons