On September 21, 2021, The Cultural Heritage Canter at the U.S. Department of State announced that the Cultural Property Advisory Committee would hear a request for a Memorandum of Understanding from “the Former Islamic Republic of Afghanistan” for a blockade on U.S. entry to goods from Afghanistan. The request came from a government that no longer existed. The request wasn’t identified as a bilateral or an emergency agreement – although different law applies to the two types. It didn’t state what types of art would be embargoed or from what period. (Some recent agreements with foreign nations have covered objects from over a million years old up to 1923.)

The law under which the request was made, the Cultural Property Implementation Act (CPIA), would require that embargoed objects be seized and returned to the “State Party.” Afghanistan is now held by the Taliban, who destroyed the Bamiyan Buddhas and the contents of the National Museum in Kabul in 2001.

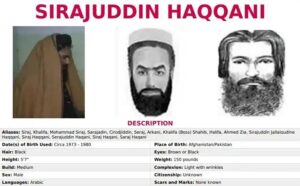

Such a request raised serious ethical as well as legal questions. The person now heading Afghanistan’s Interior Ministry and in charge of cultural heritage is Sirajuddin Haqqani, a terrorist whose organization still holds a Navy veteran hostage and who has a $10 million bounty on his head from the FBI.

Our ‘public comment’[1] on the request was lengthy. Restated and in parts expanded into four articles, it shows how

- a blockade under the CPIA would be both illegal and unworkable,

- one of the most serious threats to Afghanistan’s archaeological heritage is the expansion of the Taliban’s mining industry, which earned the Taliban some $400 million per year even BEFORE they captured Kabul,

- Afghanistan’s cultural heritage laws enabled the export of antiquities from the 50’s until 1980, and

- that an Afghanistan blockade will capture identical artworks from cross-border empires in Iran, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Pakistan.

Part 1: A Blockade on Afghanistan’s Art Under the CPIA is Illegal and Unworkable

Kabul Museum, Bodhisatva sculpture from Fondukistan, photo by Françoise Foliot, 1974-1975, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license

Since the Bamiyan Buddhas were blown to pieces and the storerooms and exhibits of the Kabul museum were smashed with sledgehammers twenty years ago, it has been obvious that a nationalist rather than an internationalist perspective on cultural policy has failed Afghanistan and other nations fraught by war and internal unrest.

More than any other crisis in culture, the Afghanistan situation demonstrates that the responsibility for preserving culture must be global. It makes clear the dark and dangerous side to cultural nationalism and ‘identity’ politics tied to exclusive ownership of the remains of ancient civilizations within modern geopolitical borders. The cultural policy pendulum has swung too far toward the nationalist perspective. It is time to restore the balance by recognizing an international, global interest.

The world has seen the brutal destruction of ‘national’ heritage by non-state actors in the last decade in the Mideast, and shuddered at the prospect of violent militants coming very close to taking power there. We have watched helplessly as ‘nationalist’ policies are used by supposedly respectable governments to advance political agendas by promoting distorted, self-serving versions of history to raise the status of one ethnic or religious group and denigrate another.

Cultural nationalism has become a useful political tool for authoritarian governments of all stripes. In excess, it does not encourage preservation of monuments or encourage archaeological excavation. It is not about patriotism or love of country either. Cultural nationalism is inherently divisive and hierarchical, a way of thinking that allows people to view themselves and their perspective as the best.

Cover, A Guide to the Kabul Museum by Nancy Hatch Dupree.

Cultural nationalism as defined by authoritarian regimes is used today to justify the falsification of history and destruction of ancient and living cultures, religions, and even entire peoples. It has raged over the last half-century over parts of the Middle East. It manifests itself in the worst violations of human and cultural rights in Egypt, Turkey, and Azerbaijan. It is the force behind the Chinese government’s destruction of Uyghur culture and the incarceration of a million people simply for being who they are in Xinjiang.

The term ‘cultural nationalism’ was unknown in the 1890s, during the reign of Afghanistan’s “Iron Amir” Abdur Rahman, but he used its arguments – that his tribe’s non-Pashtun neighbors were culturally and religiously inferior – in order to legitimize the rape, plunder and enslavement of the Shi’a Hazara peoples of Central Afghanistan.[2] One hundred years later, in 1998, the Taliban massacred an estimated 8,000 Hazaras in Mazar-i-Sharif. They have mounted attacks too numerous to count against civilians, schools, and hospitals in Afghanistan and against Hazara refugees in Pakistan.[3]

The Afghanistan situation today is, as they say, “déjà vu all over again.” Before we even get to a discussion of whether an MOU or emergency restrictions should be implemented, we must admit that there is no such thing as a “former government of Afghanistan,” that the request does not meet the foundational premises of the Cultural Property Implementation Act, and that the Taliban, with whom some relationship must be established to implement emergency restrictions or return objects, have no reason to abide by the State Department’s expectations and no track record of keeping promises made to anyone, ever. Yet the Taliban, whose Minister of Interior is a wanted terrorist, is the UNESCO State Party the U.S. must deal with to establish either an Emergency or a Bilateral agreement with Afghanistan.

Afghanistan’s Art and a Place for Exile.

What does the State Department expect this MOU to do? What will happen to Afghanistan’s cultural heritage if it cannot be safeguarded outside of Afghanistan?

Kabul Museum, Seated Buddha sculpture, photo by Françoise Foliot, 1974-1975, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license

In November 2002, in an Afghanistan Study Day at the British Museum, Paul Bucherer-Dietschi, Director of the Bibliotheca Afghanica, the Swiss Afghanistan Museum in Exile, stood on the stage incandescent with rage. He flourished a letter issued by UNESCO that reluctantly authorized the removal of boxes of packed artifacts from the National Museum at Kabul.[4] UNESCO issued the letter in the face of universal international outcry, including protests by a number of Muslim nations.[5] However, the letter authorizing the removal of Afghanistan’s most important historical and artistic heritage came too late. The reason Bucherer-Dietschi was so angry was that UNESCO had only issued it months after Taliban militiamen went to the Kabul Museum and smashed these same artifacts.[6] UNESCO had been unwilling to modify its policy that all art should remain in the country of origin, even when Mohammad Omar, Afghanistan’s supreme leader, ruled that all statues were offensive to Islam, on February 26, 2001.[7]

The loss of the Kabul museum’s collections was a disaster, leaving a black hole in Afghanistan’s cultural history, despite the secret storage of smaller, valuable objects by National Museum curators that preserved the Tilla Tepe gold hoard, now in the restored National Museum and even more vulnerable to the Taliban today.

The State Department and Cultural Property Advisory Committee now face a possible repetition of that irreplaceable loss.

Statue, probably of King Kanishka, found at Surkh Kotal, photographed in the Kabul Museum, credit Afghanistan in the Early 1960s. Smashed by the Taliban and now partially reconstructed. Some 300 of the 2,500 smashed statues have been painstakingly restored.

If ever there was a time to reconsider policies that place exclusive control of a nation’s artistic history in the hands of a national government, this is it. We do not know what policies will best serve the future. But what we do know tells us that an MOU will not help to save Afghanistan’s heritage. Such an agreement would represent a deliberate deconstruction of the aims of the governing law, the 1983 Cultural Property Implementation Act. It would absolve no one of responsibility for future acts of destruction by the Taliban, including the destruction or sale of objects returned to them. And issuance of a typical, all-embracing Designated List will only add to the hardships foisted upon the people of Afghanistan – who have already lost so much.

What the State Department and the international community should be doing now is to ensure that whatever exists of Afghanistan’s brilliant 4000 year cultural history outside of Afghanistan that can be saved, preserved, and studied – is saved, preserved and made accessible to the world, including to the people of Afghanistan for the future.

The U.S. and international community need to move immediately to take advantage of any opportunity to safeguard the materials in the National Museum of Afghanistan and archaeological excavation storerooms. Thankfully, these are better documented today and should be easy to identify and impossible to sell in any Western market. I should note that the responsible art market has already committed itself to preventing illegal sales and assisting law enforcement in the recovery of stolen objects. Nonetheless, objects must be preserved – not face the fate of the smashed collections of the Kabul Museum.

The Request of the Former Afghan Government Should be Denied as Moot.

The Afghanistan request ought to be denied as moot from the start, simply because of the lack of relations between the U.S. and whatever government the U.S. is supposed to negotiate with. Whether for a for a bilateral agreement or emergency measures, the circumstances of the request are outside of the scope of the Cultural Property Implementation Act.

- Afghanistan has no identifiable government other than the Taliban. Afghanistan’s former government does not appear to be a State Party under Article 9 of the UNESCO Convention any longer.[8]

- Afghanistan’s Taliban government has no interest whatsoever in preserving its ancient cultural heritage or respecting living cultural traditions that are not entirely in line with Taliban policies and social mores.

- The Taliban government of Afghanistan meets not one of the last three criteria for a bilateral agreement, all four of which must be met under the statute, and obviously, a “former government” cannot meet them.[9]

- Section 19 U.S.C. § 2603, Emergency Implementation of Import Restrictions applies to the following:

Chart of members of the Taliban interim government. Created by Kianosh kashefi, 9 September 2021. Wikimedia Commons, CCA-SA 4.0 International License.

(1) a newly discovered type of material which is of importance for the understanding of the history of mankind and is in jeopardy from pillage, dismantling, dispersal, or fragmentation;

(2) identifiable as coming from any site recognized to be of high cultural significance if such site is in jeopardy from pillage, dismantling, dispersal, or fragmentation which is, or threatens to be, of crisis proportions; or

(3) a part of the remains of a particular culture or civilization, the record of which is in jeopardy from pillage, dismantling, dispersal, or fragmentation which is, or threatens to be, of crisis proportions; and application of the import restrictions set forth in section 2606 of this title on a temporary basis would, in whole or in part, reduce the incentive for such pillage, dismantling, dispersal or fragmentation. (my emphasis)

Further, “(1) The President may not implement this section with respect to the archaeological or ethnological materials of any State Party unless the State Party has made a request described in section 2602(a) of this title to the United States and has supplied information which supports a determination that an emergency condition exists.

The application of Emergency Restrictions on Afghanistan material in general would not meet the statutory requirements of the law. Emergency Restrictions apply to specific types of objects, each of which would have to be shown to meet the emergency criteria above.

- Finally, there is no safe place in Afghanistan to return objects from Afghanistan. Under 19 U.S.C. § 2609, any archaeological material seized and forfeited to the U.S. must be returned to the State Party: in the case of Afghanistan, given to the Taliban.[10]

Note: A statement on behalf of the Archaeological Institute of America referenced Section 1216 of the 2021 National Defense Authorization Act (Public Law 116-283) as a safe harbor provision that could be used to hold objects from Afghanistan. However this Act does not create a legal basis for safe harbor in museums for seized objects. It would apply only to objects sent under an agreement with Afghanistan’s government and accompanied by an Afghan Government export certificate.

Afghanistan’s Ministry of the Interior/Sub-ministry of Culture is Headed by a Wanted Terrorist.

The Taliban have made promises regarding cultural heritage in the past and broken them, not so much for strategic and financial advantage but because the Taliban have never acknowledged any authority except for their own peculiar interpretation of Sharia.

FBI Wanted Poster for Sirajuddin Haqqani, Miniter of Interior (which controls the Culture Ministry) in Taliban government of Afghanistan.

In one of the first official announcements made by the Taliban government, Taliban Supreme Leader Mawlawi Hibatullah Akhundzada told his government to uphold Sharia law, and announced that Afghanistan would respect international laws and treaties “that are not in conflict with Islamic law and the country’s national values“.[11]

Afghanistan signed a number of UN human rights treaties during the 1979-1989 period of the Soviet war and under subsequent puppet governments. After taking control of the country in 1995, the Taliban violated all of these conventions.

After establishment of the interim Karzai government in Kabul, Afghanistan signed the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women in 2003, and the Optional Protocol on Convention on the Rights of the Child in 2003. It signed the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment in 2018.

Video screengrab recorded by RAWA in Kabul showing Taliban from department of Amr bil Ma-roof (Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice, Taliban religious police) beating a woman in public because she removed her chador in public. 26 August 2001, RAWA.

The former U.S.-backed government signed the 1970 UNESCO Convention in 2005, but that has no meaning for the Taliban. The Taliban Minister of the Interior, which includes the Cultural Ministry, is Sirajuddin Haqqani, on whose head the FBI has placed a $10 million bounty. The Haqqani network is behind some of the deadliest attacks against civilians, is designated a foreign terrorist organization and still holds an American Navy veteran hostage.

The new Taliban regime has made multiple statements already that, with respect to treatment of women[12] and brutal punishments and torture[13] for what the Taliban perceive as crimes, that they will honor only their own interpretation of Sharia. This allows stoning to death for infidelity, collapsing a wall and crushing a person accused of homosexuality, and cutting off hands for theft.

It is more than likely that after a brief period to lull international fears and induce the West to resume humanitarian aid, the Taliban will continue to target cultural heritage associated with other religions or otherwise contrary to its perception of Islamic norms.

For these reasons and more (outlined in Parts Two, Three and Four), the Committee for Cultural Property (“CCP”)[14] and the Global Heritage Alliance (“GHA”)[15] declined to support a proposed Memorandum of Understanding (“MOU”) with the “former government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan.”

This is Part 1 of a 4 part series.

Part One Afghanistan’s Heritage: A Former Government, the Taliban, and a Questionable Blockade

Part Three The Evolution of Afghanistan’s Cultural Heritage Law: How Communists Turned a Workable Law Against Archaeologists and Sentenced a British

Museum Curator to Death

Part Four Afghanistan’s 4000 Years of Cross-Border Empires and Trade

[1] Addressed to the Members of the Cultural Property Advisory Committee, Cultural Heritage Center (ECA/P/C), U.S. Department of State, 2200 C Street, NW, Washington, DC 20037, regarding the “Memorandum of Understanding at the Request of the Former Islamic Republic of Afghanistan,” Federal Register announcement Tuesday, September 21, 2021, Federal Register Notice: Volume 86, Number 180 (Page 52543), submitted via docket # DOS-2021-0032, date of meeting: October 5, 2021.

[2] UK Parliament, International Relations and Defence Committee: The UK and Afghanistan, Call for Evidence, submission by Hazara Research Collective, 6 Sep 2020, https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/11165/html/

[3] Id.

[4] See Kristin M. Romey, “The Race to Save Afghan Culture,” Archaeology 55 (May/June 2002): 18-, The Afghanistan museum in exile violated UNESCO and the international community’s “near-sacred policy of keeping objects of archaeological and cultural importance in their country of origin.”

[5] Luke Harding, Taliban blow apart 2,000 years of Buddhist history, 3 Mar 2001, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2001/mar/03/afghanistan.lukeharding, see also Michael Barry, Saving Our Treasures, Afghan Heritage time for exile, UNESCO Courier, March 2001, https://en.unesco.org/courier/march-2001/saving-our-treasures-afghan-heritage-time-exile

[6] Luke Harding, Kabul collection – Taliban unlock museum to show destroyed statues, The Guardian, 22 Mar 2001, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2001/mar/23/lukeharding.

[7] Jean-Christophe Peuch, Afghanistan : Taliban Edict Threatens Central Asian Cultural Heritage, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, March 1, 2001, https://www.rferl.org/a/1095862.html

[8] 19 U.S.C. § 2602(a)(1)

[9] 19 U.S.C. § 2602(a)(1)(A-C)

[10] 19 U.S.C. 2609(b)(1)

[11] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-58479750

[12] News reports from just the last few days provide a sampling of the violations of such conventions by the Taliban: Afghanistan: Taliban Abuses Cause Widespread Fear; Women in City of Heart Describe Loss of Freedoms Overnight, Human Rights Watch, Sep 23, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/09/23/afghanistan-taliban-abuses-cause-widespread-fear, and Former Afghan police women being killed, forced into hiding after Taliban takeover, PBS, Sep 14, 2021, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/former-afghan-police-women-being-killed-forced-into-hiding-after-taliban-takeover

[13] Taliban hang body in public,: signal return to past tactics, PBS, September 25, 2021, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/taliban-hang-body-in-public-signal-return-to-past-tactics

[14] The Committee for Cultural Policy (CCP) is an educational and policy research organization that supports the preservation and public appreciation of the art of ancient and indigenous cultures. CCP supports policies that enable the lawful collection, exhibition, and global circulation of artworks and preserve artifacts and archaeological sites through funding for site protection. CCP deplores the destruction of archaeological sites and monuments and encourage policies enabling safe harbor in international museums for at-risk objects from countries in crisis. CCP defends uncensored academic research and urges funding for museum development around the world. CCP believes that communication through artistic exchange is beneficial for international understanding and that the protection and preservation of art is the responsibility and duty of all humankind. The Committee for Cultural Policy, POB 4881, Santa Fe, NM 87502. www.culturalpropertynews.org, info@culturalpropertynews.org.

[15] Global Heritage Alliance (GHA) advocates for policies that will restore balance in U.S. government policy in order to foster appreciation of ancient and indigenous cultures and the preservation of their artifacts for the education and enjoyment of the American public. GHA supports policies that facilitate lawful trade in cultural artifacts and promotes responsible collecting and stewardship of archaeological and ethnological objects. The Global Heritage Alliance, 5335 Wisconsin Ave., NW Ste 440, Washington, DC 20015. http://global-heritage.org/

The empty niche that once held the Bamiyan Great Buddha. Photo © Don Meyer.

The empty niche that once held the Bamiyan Great Buddha. Photo © Don Meyer.