As part of our special Afghanistan issue, we are covering aspects of traditional ethnographic, historical, and ancient art that are little known outside of the region. This year, U.S. activists successfully advocated for radically over-broad bans on imports of Turkish goods entering the U.S. The banned Turkish goods cover objects from over a million years old to 1923. They include Turkish carpets and textiles, which despite hundreds of years of commercial production for a global market, are now deemed ‘cultural heritage’ whose ownership should be controlled by Turkey’s government. A similar ban applied to Afghanistan would seriously impact its people and in the end, fail to protect its cultural heritage.

Tent bag, torba, pile woven wool,

Turkoman, Amu Darya region, northern Afghanistan. Photo by Kate Fitz Gibbon, private collection.

We thought our readers might want to know more about textile production by women in Afghanistan, for whom textiles and carpets are commodities as well as objects for home and adornment. Weaving and embroidery skills are sometimes the only economically viable talents that rural Afghan women possess. Their personal property, passed on through generations, is the family bank account.

Moreover, because the Taliban hold to one version of Islam, and many other Afghans embrace a less rigid and narrow perspective, it may be helpful to place Afghanistan’s traditional culture where it belongs, in a deeply felt Muslim identity that is fundamentally resistant to extremism. Articles like this one – about an intensely creative yet traditional activity in the women’s sphere – will broaden our readers’ understanding and appreciation for Afghanistan’s amazing craft traditions. There are dozens of books on Turkoman carpets available to the curious reader, but very little on other Turkoman textiles. We hope this will help to fill that gap.

Introduction

The textile arts of the Turkoman, who are best known for weaving luxurious pile carpets, also include beautiful and technically sophisticated embroidered garments and accessories. These embroidered objects are made by the women of the family primarily for members of their own households, but some are also sold in town markets.

Carpet weaving, Jowzjan 1977, Anneliese Stucki, “Horses and Women: Some Thoughts on the Life Cycle of Ersari Turkmen Women,” Afghanistan Journal 5:4 (1978): 140, 148.

For women living in villages and smaller settlements in the north of Afghanistan, traditional costumes are more than luxury garments and accessories. Women’s costume is always an important marker of ethnic identity in Central Asia; it tends to remain fixed long after men’s garments have adapted to modern, European styles.

For Turkoman women, rites of passage related to adolescence, marriage, and childbirth each required a major alteration in daily dress, ornament, and hairstyle. These close ties between women’s costume and major life transitions helped to preserve traditional modes of dress. While men and boy’s clothing changes little from youth to old age, a woman’s garments are specific to periods in a woman’s life, denoting her status from child to matriarch.

Many embroidered textiles that were worn as or decorated garments have symbolic significance. These function as talismans or incorporate talismanic or protective forms within a textile’s design. While a simple triangular shaped embroidered pendant is the most common textile decoration, other embroidered textiles are decorated with patterns or appliques that reference powerful attributes of certain animals. Protective textile ornaments and garments are virtually universally used – a person, male or female, simply wouldn’t feel right without them.

Turkoman family arriving at Aqcha weekly market, circa 1975, photo Kate Fitz Gibbon. Note the leather triangular talisman worn by the horse.

Soviet researchers – who as proponents of atheism had an obvious axe to grind against Islam – have often claimed that this sort of women’s textile magic is the unconscious remnant of long-forgotten shamanic traditions. The official Soviet anthropological line was that Central Asian Islam was a syncretic phenomenon saturated with ancient local elements and therefore, not very Islamic at its core.

That was and is nonsense. Talismans and talismanic images are created by people throughout Afghanistan whose Islamic identity is deeply rooted and whose Islamic practices are an intrinsic and inseparable part of daily life. It is because the Turkoman are so sure of who they are and so comfortable in their Islamic identity that they can continue practices that are traditional within their own communities without worrying that they are straying from someone else’s more narrow definition of acceptable Muslim behavior.

Turkoman women make embroidered textiles, together with carpets and weavings whose designs may also reference these protective qualities, for many reasons. They do so in order to renew their identity within a family and a tribe, to strengthen tradition, and to reinforce the Turkoman-ness of everything they do. Turkoman women’s textiles are practical, decorative, and magical all at the same time.

For the Turkoman, as for many others in Afghanistan, ascribing a protective function to an embroidered triangle of cloth is no different from visiting a saint’s grave to pray for children or good health or tying ribbons to revered, ancient trees while saying prayers beneath them. These are all culturally reinforcing actions. The Turkomans’ strong sense of identity extends throughout Turkoman culture – there is no conscious distinction between traditional community practices and the practice of Islam.

A Short History of the Turkoman

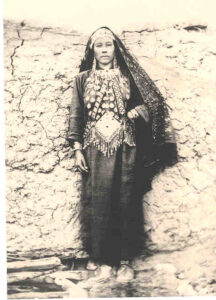

Turkoman woman in festive garb wearing chyrpy, circa 1880s, Photo by Henri Moser, private collection.

The ancestors of today’s Turkomans began to arrive in Central Asia about the 5th century CE, inhabiting the southern steppe region in what is today Turkmenistan, northern Afghanistan, northern Iran and eastern Turkey. Some of these Turkic language-speaking peoples took Constantinople and formed the foundation of the Ottoman state. Other waves of Turkic migration followed; the largest group arrived with the armies of Chengiz Khan. The relatively easy mobility of the Turkoman’s nomadic lifestyle as steppe pastoralists and the frequent warfare in the region brought the Turkoman tribes into different areas over time. Later tribal organizations grew from political coalitions that formed under powerful leaders and took control of the various regions of delta, steppe and oasis lands.

While Turkoman populations extend far into Anatolia, a distinctively Central Asian Turkoman cultural identity evolved through centuries of living in close proximity on the steppe. A well-defined ethnicity also separated the Turkoman from other Turkic language groups in the same geographical area such as the Uzbek, the Kirgiz and the Kazakh. By the mid-nineteenth century, sub-tribes known as the Tekke, Chador, Yomud, and Ersari were among the largest Turkoman tribes in the region, and sub-tribes of these groups along with dozens of smaller groupings were found in different locations in the steppe.

Today, the Turkoman tribes are widely distributed across Central Asia. Turkomans inhabit the eastern shores of the Caspian Sea and the borders of the Kopet Dagh range from Ashkhabad to Mary (ancient Merv). Various sub-tribes of Turkomans are found living on both banks of the Amu Darya from where it flows from the Pamir Mountains of northern Afghanistan, in scattered areas along its length and at its end in the delta region of the Aral Sea.

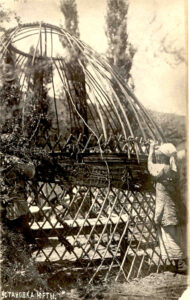

Turkoman woman assembling a yurt, circa 1920s-1930s, Photographer unknown, private collection.

These regions at the edges of desert lands were considered uninhabitable, dangerous wastelands by others, but they were admirably suited to the Turkomans’ semi-settled, herding economy. The Turkoman turned their inaccessibility to advantage, using the deserts to flee from attack or escape with captured booty. Until the beginning of the twentieth century, the Turkoman tribes’ pastoral economy was supplemented by mercenary activities for nearby Uzbek rulers, slave raiding from the adjacent Persian regions to the south and pillage of traveling caravans. These warlike activities made the Turkoman undesirable neighbors and for the most part, other ethnic groups and political organizations avoided the Turkoman regions.

Most pastoralist Turkomans lived in latticework wood and felt tents (yurts), in groups ranging from a few families to tented communities of several thousand persons. They raised horses, camels and goats and bred karakul sheep. Although many Turkoman were forced to move from pastoralism to agriculture in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many have retained close ties to nomadism and still identify culturally with an idealized steppe life, using both mudbrick buildings and yurts for different times and purposes within a household, and even placing yurts in the courtyards of fixed dwellings in cities.

The continuation of many steppe traditions is most prevalent among the Turkoman of Afghanistan. While parts of Afghanistan adjacent to the Amu Darya and proximate to what is now Turkmenistan have long held diverse Turkoman communities, large numbers of Turkomans emigrated to Afghanistan in order to avoid military aggression, repression and seizure of goods under Czarist Russian imperial expansion, and then forced collectivization and starvation under the Bolsheviks.

A Textile Economy

Camel bag, juval, pile woven, wool, Turkoman, northern Afghanistan. Photo by Kate Fitz Gibbon, private collection.

Over the centuries, each Turkoman group had developed distinctive, sophisticated textile arts that were suited to a nomadic lifestyle. Rugs, kilims, tent bands, camel trappings, storage bags and other utilitarian weavings made up almost all the furniture of the home. A family’s household goods could simply be folded up and loaded onto a camel and taken to the next camping ground. In part because family wealth needed to be easily transportable, the Turkoman also created a variety of styles of extraordinarily refined and elaborate silver jewelry.

The Turkoman woman’s contribution to the economic well-being of her family as weaver and textile maker is another reason that brides and young married women wear an extraordinary amount of gold-washed, carnelian-studded silver jewelry. It is not uncommon for a bride, a kelin, to wear five to ten pounds of traditional silver ornaments. The groom is responsible for paying for much of this bride-wealth – which stays with the woman after marriage. It is a very expensive business to marry a woman who will contribute significantly to the family economy. Certainly, this economic role contributes to the fact that, while there are clearly demarcated spheres of influence for men and women, women are generally more openly recognized as decision makers in Turkoman communities.

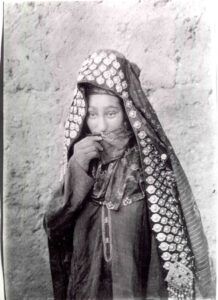

Turkoman woman wearing silver ornamented chyrpy, 1920s, unknown photographer, private collection.

A Turkoman woman is not just a woman today, she is a carpet factory in her own right. Turkomans have been renowned for centuries as the premier carpet weavers of Central Asia. Great value was placed on a woman’s skill and artistic ability to create unique combinations of traditional motifs and colors.

In the second half of the 19th century, Turkoman women became even greater economic contributors to the family as carpet weavers. A rapid expansion in commercial weaving took place when traditional sources of income such as mercenary service and slave trading were disrupted. While the skill of a family’s weavers is still an important measure of family pride, carpet patterns and styles have been radically affected by the demands of the commercial market. Made-to-order carpets are often overly precise and repetitive in pattern and no longer express a unique tribal or family identity.

In contrast, embroidery never became a truly commercial activity. It has remained primarily an internal pursuit, a luxury production in which beautiful work enhances the status of the maker in her family and community.

Headdresses and Robes

Turkoman women embroider the edges of their robes, dresses, trousers and headdresses. They make embroidered bags for tools, mirrors and ceremonial breads, children’s garments and a wide variety of caps. All of these are prestige items, all are decorative – they make the wearer more handsome or add to the beauty of the home – and all carry patterns that are drawn from the same reservoir of traditional designs.

Turkoman woman in festive gear, Jowzjan 1977, Anneliese Stucki, “Horses and Women: Some Thoughts on the Life Cycle of Ersari Turkmen Women,” Afghanistan Journal 5:4 (1978): 140, 143.

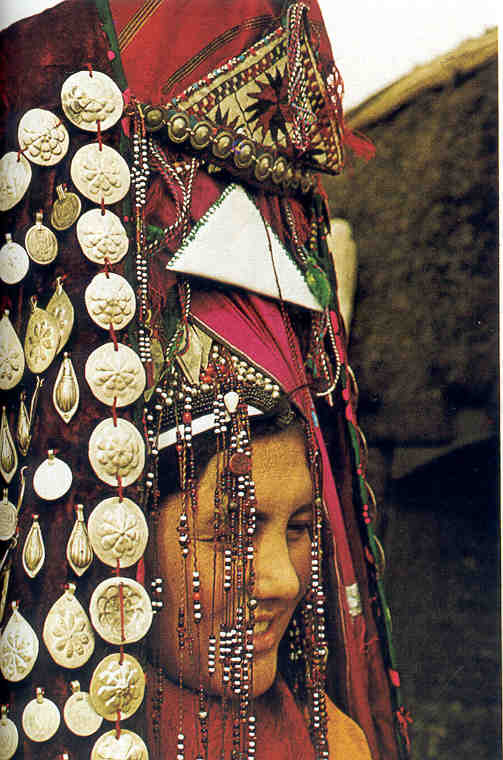

Until the birth of her first child, a newly wedded girl wore an elaborate costume and much jewelry even while doing daily housework. Like virtually all Central Asian traditional women’s costume, a Turkoman outfit consists of a tunic or dress worn over wide trousers, topped with an open-front robe. The Turkoman headdress is unique. Several silk scarves are wound around a frame to form the base. In the case of young, married women, the headdress can be quite tall, over 30 cm in height, and is decorated with silver frontlets, plaques, silver and glass beads, and numerous pendants. On formal occasions an outer-robe hangs over the top of the headdress at a rakish angle, and may be pulled over the face if a woman feels shy. The outermost robe is the most highly decorated garment in the repertoire of Turkoman costume; it may be embellished with silver jewelry or coins. Most robes worn by Turkoman women were decorated with embroidery only at collar, cuffs and hem, often with patterns based on ram’s horns, gochak.

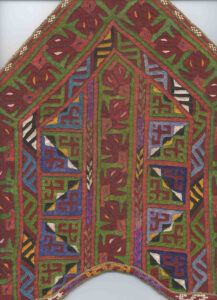

The most famous examples of Turkoman embroidered costume are the false-sleeved chyrpy robes worn atop the head by married women of the Tekke Turkoman tribe. Traditionally, the chyrpy had almost a cape form, with empty, flat, closed sleeves that hung down the back and were tied together with black and white twisted strings or a rectangular cloth panel. From the 1940s- 1950s onward, Tekke tribe chyrpy robes had actual sleeves in which the arms could be placed but which nevertheless were not used when worn atop a headdress.

Embroidered chyrpy, back, Turkoman, collected Afghanistan. Photo by Kate Fitz Gibbon, private collection.

Embroidered chyrpy, back, 19th c. Turkoman, collected Afghanistan. Photo by Kate Fitz Gibbon, private collection.

The Tekke Turkoman chyrpy was not decorated with silver; it was covered with virtuoso embroidery-work instead. Tekke Turkoman girls were not thereby deprived of silver jewelry. A well-to-do Tekke Turkoman bride could also wear up to ten or twelve pounds of beads, bracelets, crown, pectorals and other massive silver ornaments.

Black, very dark blue or very dark green silk was the background material for robes embroidered by young brides-to-be. The main embroidered field patterns for chyrpy were always tulips, flowers glowing with life and fertility and the joys of springtime. These pit-da patterns were arranged in tightly packed rows or in a variety of branching patterns. Every year on the steppe – right at the solstice – the green pastures turn suddenly a brilliant red, as millions of small species tulips burst into bloom. They are the perfect image for the marriage robe.

Embroidery on chyrpy always included other pattern elements such as rhombus or geometric patterns on the collar and multiple small border patterns on the cuffs and edges of the robes. The pishme pattern was very popular for borders; it was named after the little square cakes eaten at the celebration after a birth.

Pair of embroidered doga, talismans, Turkoman, Amu Darya region, northern Afghanistan. Photo by Kate Fitz Gibbon, private collection.

There are far fewer yellow silk chyrpy than dark blue or black ones. The yellow-ground chyrpy are thought to be made by mature women of middle age; some yellow-ground robes display the highest technical quality of needlework made by the Turkoman. The most rare Turkoman robes are chyrpy with a white ground; these are often said to be reserved for elderly women. Most white-ground chyrpy have rather spare, even sketchy, embroidered patterns.

While Turkoman women in the former-Soviet state of Turkmenistan adopted European-influenced shift-dresses under pressure from the government, and some abandoned traditional trousers, they continue to embellish the edges of their garments with embroidery and to make elaborately embroidered robes for weddings and other festive occasions. On the Afghanistan side of the Amu Darya, many Turkoman women retain full traditional costume, identical to that of the nineteenth century, even today.

The ubiquitous triangle-shaped doga is found throughout Central Asia, widely distributed among people of different ethnic and linguistic groups. These small talismanic triangles are worn by people of all ages, attached to horse’s harness, tied to cradles, or hung in houses or yurts.

Doga often contain some material that enhances their power as amulets; a scrap of paper on which verses from the Koran have been written, a bit of salt or coal, a rag from the clothing of a powerful person, a stick of dagdan wood, or a bit dried herbs. The triangular form of doga is also found in a great many items of silver jewelry worn by Turkoman children and young women.

Childbearing and Women’s Magic

Among the Turkoman, children and women of childbearing age are considered vulnerable to evil influences from human and spirit contacts. The most dangerous of these are the evil eye, which causes sickness and death to small children, and the albasty, an evil female spirit who appears sometimes as a goat but most often as a woman with hair to her heels and an open wound on her back, through which her entrails are always spilling.

Giving birth was perilous for mother and baby in rural villages and on the steppe; and young children suffered a very high infant mortality in Afghanistan. Many families were completely without access to doctors and limited educational opportunities meant women had little knowledge of disease or practical hygiene. Traditional avoidance and purification rituals involved seclusion of young mothers and their babies and ritual immersions in special baths during chile, the first forty days after birth. Tiny children were swaddled and wrapped with specially decorated appliquéd and embroidered baby bands in their cradles.

Turkoman child’s protective garment, elek, detail, silk embroidery on cotton. Afghanistan, Amu Darya region. Photo Kate Fitz Gibbon.

Turkoman child’s protective garment, elek, silk embroidery and patchwork on cotton. Afghanistan, Amu Darya region. Private collection. Photo Kate Fitz Gibbon.

Slightly older Turkoman children were dressed in tiny versions of adult clothing and embroidered caps with triangular doga, owl feathers and other amuletic devices. Between the ages of about one and a half and five years, when children were first getting up and about on their own, they also wore an especially protective garment called elek, aga elek, kyurte, olfak or gyrama among the various Turkoman tribes.

These garments are of two types. One form, the size of a large double bib, has a lozenge shape and sometimes has triangular additions at the shoulder. Beautifully embroidered examples of this type of elek are found particularly among the Turkoman living along the Amu Darya in and near Afghanistan.

The other type of elek is shaped more like a poncho or shirt open at the sides and is found primarily in the Turkmenistan region. The poncho-like garments often have appliqué work and sparse embroidered decoration on the breast, shoulder and upper back, where small coins and jewelry elements are sewn on. The poncho form is often unfinished at the bottom ends. Sometimes a child wears both bib and the poncho forms at the same time.

Part of the elek’s function was to protect the child from the evil eye, which could be cast quite unwittingly by anyone outside of the family. But sayings collected from Turkoman about the garment infer that it also developed emotional and intellectual qualities in the child who wore it. “A person who doesn’t wear the elek, thinks too much of himself,” and “Without an elek, the head is full of wind, everyone knows that.”

Turkoman child’s protective garment, elek, detail, embroidery with with appliqued snake detail. Private collection. Photo Kate Fitz Gibbon.

Turkoman elek, protective garment for child, pile woven. Photo Kate Fitz Gibbon. Private collection.

Specifically male ornaments might be placed on the center of the back of a young boy’s elek when he was between two and seven years of age; a miniature sword or dagger, or the aq ai, a stylized bow and arrow of silver which encouraged him to grow brave and sturdy. For a child of either sex, the mother might add a wriggling, multicolored snake to the elek in appliqué or embroidery raised slightly above the embroidered background. Soviet researchers have written often that stylized snake and frog patterns are used especially on elek, and that both snake and frog are endowed with powerful sacral qualities. According to Soviet sources, the pattern called “scorpion’s maw” occurs often with the “snake’s head” pattern, but both are highly abstracted, sometimes appearing as simple lines set at right angles to one another. Several flower motifs are described as having significant protective power to breastfeeding mothers, such as the gul-i-badam or almond-flower, a familiar border pattern in carpets, which is a common motif in the embroidery of Turkoman in Afghanistan. Other talismanic elements include a lock of hair from a healthy child’s first haircut or a tuft of camel’s fur. The predominant motif of embroidered elek, however, is the triangle, which echoes the shape of the doga talismans.

All Turkoman wear hats or headdresses. There are dozens of sayings prevalent in Central Asia expressing the belief that “A man’s soul lies in his hat.” The best-known Turkoman style of headgear is the tall sheepskin hat, under which Turkoman men wore a lighter skullcap embroidered by women of the family.

Young woman’s hat, Turkoman, Amu Darya region, northern Afghanistan. Photo by Kate Fitz Gibbon, private collection.

Children of both sexes wore hats at all times. Their heads were shaved until reaching puberty; the boys were left a lock at the back, and the girls kept only their bangs, temple-locks and sometimes a little tail at the back. A slim skullcap was perfect for covering the shaved areas, and no child was without one.

At puberty, the girls began growing their hair, plaiting it into at least four braids as soon as they were able. Adolescent girls changed to the cap for girls of marriageable age, a soft, tall-peaked hat in a form reminiscent of a miniature yurt. These caps were sometimes decorated with embroidery, tufts of feathers, beads and coins. A cupola shaped silver ornament was sewn to the top of the cap, and when a girl became engaged, she would add a white owl’s feather to the top of the cupola.

Camel Covers

While a beautiful horse is a Turkoman’s greatest pride, camels are important prestige animals. A camel is a symbol of solid wealth. In Turkoman tradition, camels are also deeply connected to women’s tradition and birth through association with the camel’s lengthy gestational period.

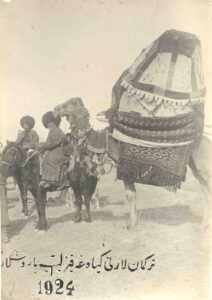

Procession bringing a Turkoman bride to her new family in bedecked camel. Photo by Divanov. 1924. Private collection.

An important element of Turkoman wedding ceremonial is the bringing of the bride to her new home on the back of a specially decorated camel. She sits in an open framework of wood, rather like a yurt in shape, which is covered with textiles. The framework rests on a luxuriously decorated silk camel cover.

The traditional Turkoman camel cover is very large and made of pieced, embroidered and otherwise embellished silk fabrics. The silk patchwork repeats the diamond shapes of jewelry and embroidery emphasizes triangular doga talisman shapes. The bride is seated at the center, surrounded by amulets made of tufts of feathers and locks of hair from the first haircut of healthy babies. The bride is completely surrounded by propitious forms and is the focus of powerful protective forces.

Small Bags Substitute for Pockets

Bag, khalta, Turkoman, Amu Darya region, northern Afghanistan. Photo by Kate Fitz Gibbon, private collection.

Both men and women carried tea and other personal items in small embroidered bags called khalta. Turkoman men rolled khalta into their sashes on trips to market; at the teahouse, the bags were subtly shown off to demonstrate family pride in their wives embroidery skills. These bags show a highly imaginative working of color and patterns. Often, Turkoman khalta bags echo the border patterns of carpets such as the gul-badam, “almond flower” pattern but the color palettes reversed; red is the dominant color in carpet weaving, but green predominates in embroidery.

Embroidery Techniques

Turkoman woman doing embroidery, circa 1900, photographer unknown, private collection.

Turkoman women worked sitting on the floor or ground. They stretched the cloth to be embroidered against the crook of the left knee, attaching the cloth with a needle. They embroidered with a plain needle, not a hook. Turkoman did not draw out embroidery patterns or uses stencils, embroidery canvas or a frame. While they very occasionally used a light stitch to mark out a pattern, almost all embroidery was done simply by eye.

The stitches utilized by Turkoman embroiderers were keshde, a loop stitch; ilme or kodjume, a looped chain stitch; gayma, a point or dot stitch used for embroidery of caps and sleeves; basma, a solid, single-sided fastening stitch; chirazi, a crossed stitch; and garalama, a stem stitch. Turkoman women frequently use appliqué, gurama, especially to attach small triangles of cloth or felt to garments and hangings. A common appliqué technique called germezdonlyk involved attaching a bordering ribbon to decorate hems, cuffs, and side slits.

There are many designs tied to the women’s economy: a “carding comb” pattern and one called “spinning wheel”. There are many patterns named after domestic animals, “camel’s neck”, “cow’s track”, “chicken’s beak” and “dog’s tail”.

The patterns of embroidery, like the embroidered objects themselves, are reflective of and intrinsic to Turkoman women’s daily lives. This interweaving of the artistic into domestic life is a primary characteristic of the Turkoman aesthetic. Although the Turkomans’ possessions are relatively few, they are born connoisseurs and each homemade garment or textile is beautifully adorned by their own hands.

Kelin wearing brenjäk – coat, Jowzjan 1977, Anneliese Stucki, “Horses and Women: Some Thoughts on the Life Cycle of Ersari Turkmen Women,” Afghanistan Journal 5:4 (1978): 140, 143.

Kelin wearing brenjäk – coat, Jowzjan 1977, Anneliese Stucki, “Horses and Women: Some Thoughts on the Life Cycle of Ersari Turkmen Women,” Afghanistan Journal 5:4 (1978): 140, 143.