Searching for antiquities is legal with landowners’ permission. It is illegal to metal-detect on (or

remove items from) protected sites. Treasure belongs to the Crown. Courtesy Michael Lewis.

A June 6, 2024 international webinar, ‘A Closer Look at the Portable Antiquities Scheme’ organized by the Antique Coin Collectors Guild (ACCG) presented on the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) and the operation of the Treasure Act; the PAS operates throughout England and Wales, through the Treasure Act, and covers Northern Ireland as well. Operated by the British Museum in England, the Portable Antiquities Scheme is widely known as the world’s most successful program to encourage the reporting of archaeological finds made by the public and secure finds of ‘treasure.’ The main aim of the PAS is to document all finds to advance knowledge and encourage public and academic research on all levels. The Treasure Act offers museums the opportunity to acquire the most important finds with rewards made to both landowners and finders for following best practice. Besides recording finds, the PAS supports the excavation of items found in situ (like coin hoards), so they can be properly understood.

The Treasure Act 1996 has resulted in huge increases in the number of found artifacts being reported – fifteen to twenty times more than before. The Portable Antiquities Scheme was introduced at the same time to encourage the voluntary reporting of all archaeological finds. By following the reporting rules, the finders and landowners are either compensated, or if museums do not wish to acquire the found objects, they are returned to the finders for their own use, including sale.

In just a few decades, the PAS has not only vastly increased the number of reported finds of treasure and archaeological and historic objects, but it has also dramatically altered the relations between metal detectorists, archaeologists, scholars, and cultural institutions in England and Wales, making them all partners in preserving heritage.

The speakers at the webinar were Professor Michael Lewis of the British Museum and Head of the Portable Antiquities Scheme, Angie Bolton, Curator of Archeology, Oxfordshire Museum Service, and Randolph Myers, a Board Member of the Ancient Coin Collectors Guild.

6,000+ Treasure finds acquired by 250 museums. Courtesy Michael Lewis.

Professor Lewis’ presentation provided details on the operation of both the Portable Antiquities Scheme and the Treasure Act 1996, and how the PAS process has enriched the documentation of archaeology in England and Wales, recording over 1.7 million objects in less than three decades in a publicly accessible database. This database is currently being used for almost 900 research projects.

Ms. Bolton discussed how objects discovered through the PAS were chosen in order to fill gaps in her museum’s collections and serve local and national research interests, and to tell particular stories to the Oxfordshire public: how objects were accessioned and how she and her staff prepared, stored, and exhibited the finds obtained from the PAS, many of which were ancient coins.

Randolph Myers explained how U.S. laws impacted the collecting of ancient coins, pointing out how ethical, responsible collecting was encouraged by the PAS’s voluntary reporting and reward scheme, and discussed how the U.K. approach could be adopted to benefit archaeology, research, and the independent study characteristic of coin research in the U.S. and around the world. He concluded with a case study of a hoard uncovered in Somerset in 2013 that was processed through the PAS and which eventually became in large part available to international collectors including in the U.S., with no loss of archaeological or scientific value.

Each presenter has made their complete slides available on the ACCG website and additional background and each lecture presentation follows.

Professor Michael Lewis of the British Museum, Head of the Portable Antiquities Scheme

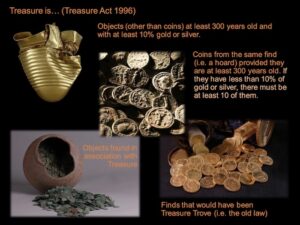

Treasure Act 1996. Objects (other than coins) at least 300 years old and with at least 10% gold or silver. Coins from the same find (i.e. a hoard) provided they are at least 300 years old. Objects found in association with Treasure. Courtesy Michael Lewis.

Treasure legislation goes back a long time – essentially, there has been treasure law ever since medieval times; there are aspects of it that are quite antiquated. In medieval times the king could claim all the gold and silver in the ground that didn’t appear to belong to anyone else. To illustrate this point, one of the biggest treasure finds in the British Museum – although legally it’s not ‘treasure’ at all – is the Sutton Hoo treasure found in 1939. It was an Anglo-Saxon burial ship that contained lots of precious objects. Under the old legislation we had , things had to be buried with the intention of recovery, and a coroner had the role of determining whether that was the case. Now, in the instance of the Sutton Hoo burial the Anglo Saxons who buried it hadn’t really intended ever to come back for it, so it was declared not to be treasure. Thankfully for the British Museum, Edith Pretty, the landowner, donated the whole find to the British Museum. In 1996, the government decided to review the legislation. The definition is now quite complex but in a nutshell treasure is basically gold and silver objects over 300 years old. If it consists of coins and they’re made of gold or silver, there must be two or more of them in the same place. Items found with treasure are also treasure: a good example is a coin hoard where the pot would be treasure because it’s the container for the coins which are treasure. Also, finds that would have previously been treasure trove (under the old legislation) can be under the newer legislative processes, capturing hoard less than 300 years old. The Act also allows the Secretary of State to define new types of things as treasure. In 2003 it was decided that prehistoric base metal assemblages could be treasure as well. Very recently, in June 2023, it was decided that objects that provide an outstanding insight into an aspect of archaeology and cultural history can be treasure. This is a very new definition, but it’s got a very high threshold. It’s not designed to capture many objects, only those that are absolutely amazing.

What normally happens is if the finder makes a discovery, they have a legal obligation to report it to the coroner in the district in which it was found within 14 days. In the United Kingdom coroners normally deal with death inquests so their treasure work is a leftover from medieval times. In practice the finder normally deposits the objects with the local Finds Liaisons officer.

A report then is produced for the coroner outlining why the expert, the archaeologist thinks that the object is treasure. Normally the finder agrees with us and then it’s offered to a museum to see whether they want it. If the museum wants it then it goes through the next part of the process. If they don’t it’s disclaimed, returned to the finder and then finder can do what they like with it – sometimes these items are sold. If a museum wants it, then the object is valued by an independent committee called the Treasure Valuation Committee and a reward then is payable that’s equal to the value of the find, which the finder and the landowner share 50/50 normally.

Amendments to Treasure Act. Prehistoric base-metal assemblages, and any prehistoric gold object. Items (over 200 years old) that provide an ‘outstanding insight’ into any aspect of archaeological, or cultural history. Courtesy Michael Lewis.

That’s what normally happens. If somebody’s done something wrong – failed to report or tried to hide a sale – then the reward might be reduced. We’ve had a massive increase in treasure cases over the years, especially since the beginning of 2003 when the Portable Antiquities Scheme was expanded to the whole of England and Wales. The number of cases is increasing year on year – going up exponentially. When the treasure legislation came into force, archaeologists wanted it to capture new sorts of objects. Then there was a big concern that lots of people were finding archaeological objects and there was no mechanism for these to be captured so that the objects and their information could be used for archaeological purposes. It was decided to set up pilot schemes for the recording of archaeological finds outside of the Treasure Act and to facilitate the reporting of these finds.

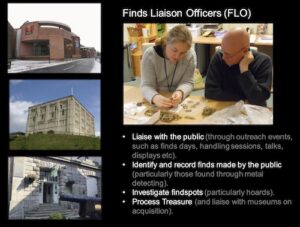

Archaeologists, known as Finds Liaison Officers (FLOs), based at local museums have the job to liaise with the public through various outreach events such as Finds Days, handling sessions, public talks and creating displays. The main part of their job is to identify and record archaeological finds and add those to our database. They also investigate findspots if necessary, so if people find a hoard in situ it can be archaeologically excavated.

The FLOs are the main connection between the finder community, mostly consisting of detectorists and museums and the wider heritage establishment. On the PAS database, which anyone can log on to if you go to finds.org.uk, you will see the records of all the objects that have been recorded whether they’re treasure or not. Now there’s over 1.7 million objects recorded.

Finds Liaison Officers (FLOs) Liaise with the public (through outreach events, such as finds days, handling sessions, talks, displays etc). Identify and record finds. Investigate findspots. Process Treasure. Courtesy Michael Lewis.

It’s been terrific in terms of recording data. The reason we’re doing that, of course, is to advance archaeological knowledge, not just for the fun of it as it were! But anyone can get on that database and see images of those objects. A great many of them are coins. The public cannot see specifically where objects have been found – that’s restricted on the online version of the database. However, all kinds of researchers can have in-depth access to see exactly where those objects were discovered for archaeological purposes and serious research.

We’ve already recorded 35,000 objects this year. You can see from this graph that it seems like the Romans were throwing everything away all the time! About 50% of the data seems to be from the Roman period. It’s important to note that when it comes to the post medieval period, we are quite selective in what we record from about 1550 onward. It’s a resource issue. Certainly after 1700, when things get industrialized, we don’t have the resources to record everything that is found.

Most of these finds are made through metal detecting, but we also record finds found by someone digging in their garden or going out for a walk and spotting something in the ground. Metal detectorists are going out looking for archaeological finds, so it’s no surprise that they’re the people that find most of these objects. Importantly, from an archaeological perspective, most of these finds are made on cultivated land. Most of the time, finders aren’t digging into archaeological contexts. Objects are often brought to the surface by plough damage and then the finders recover these objects. These objects then provide clues about what’s going on beneath the ploughed soil.

Lots of research has been taking place using the PAS. Over 200 PhD researchers have used PAS data as a principal source. So have major archaeological research projects. My slide lists only researchers asking for very specific high-level access to the database. There are lots of people researching these objects in a more superficial way as well.

Entirely new sites have come to light through the PAS, like one in Suffolk Rendlesham where amazing archaeological features have been discovered as a result initially of metal detecting and then afterwards through archaeological field work.

Rendelsham revealed. Anglo-Saxon Life in South East Suffolk. Courtesy Michael Lewis.

I did a study with a colleague of mine where we were looking at the relationship between PAS data from the medieval period and medieval market sites. You can use this data to understand the economic viability of these different sites. Many of these market sites were formed as status symbols but their economic viability varied quite considerably. The PAS data has enabled us to understand better why one site succeeds and another doesn’t and the relationship between these different places. I’m also involved with a project where we’re examining how everyday people expressed their religious beliefs in the Middle Ages.

In England and Wales we have a Code of Practice for Responsible Metal Detecting to tell people how to do what they do in a better way than they might otherwise, and we also provide advice to landowners, promoting the recording of all finds.

I was just going to talk very briefly about the funding – the Portable Antiquities Scheme is funded principally through government through the Department of Culture, Media and Sport. A grant is made to the British Museum and then the museum gives money to local partners. As Angie knows, that money doesn’t completely pay for everything. It’s a partnership project. From the British Museum perspective, to enable local partners to have archaeologists within their staff adds a wider dimension to what they’re doing. We cover most but not all of the costs and indeed there’s a significant local partner in kind contribution as well in terms of office space and resources etcetera.

The staff time of people like Angie contributes to the work of the Finds Liaison Officers as well. It’s a team effort. We’ve got about 100 partners across England and Wales. Really, we’ve been lucky in recent years that the government has supported the Portable Antiquities Scheme with more money. They’ve also given more money in the last Spending Review for the administration of the Treasure Act so that’s welcome news.

Recording finds for the Portable Antiquities Scheme. Courtesy Michael Lewis.

To look at a few things going forward in the future – there are some exciting things happening. The first one is that there’s an All Party Parliamentary Archaeological Group inquiry that is looking to foster more the relationship between archaeologists and metal detectorists. What’s really important about this is not only that it recognizes the real importance of the Portable Antiquities Scheme but also the pressures that it’s under as well. In the UK there are probably about 40,000 metal detectorists and there are only about 40 Finds Liaison Officers so they’re up against it in terms of recording the information that detectorists record. Obviously, it’s a one off opportunity – if a finder doesn’t tell you about the things that he or she has discovered then that opportunity to learn has evaporated. It’s really important that we are as efficient as we can be in recording as much material as we can but also to have the Finder community on our side as well. We don’t know who the Prime Minister’s going to be in a month’s time and that will have an impact on how our history and heritage will be addressed. Like a lot of countries in Europe, we’ve faced a period of limited funding. A new government whatever it might be will have certain priorities – and we all know heritage and culture generally come a little bit lower down the list than most things. We’ll have to wait and see what happens but we’ve generally been treated quite well by successive governments so we’re optimistic.

An important and interesting thing is that we’re redeveloping the PAS database at the moment. It’s on end-of-life technology and could be a lot more user-friendly. It could do things in a way that not only makes it easier for us to record archaeological finds but also for people to get information out of the data. We hope to have a new database by the end of next year. Upgrading the website will help people report treasure and go through that treasure process. We’ve also had some really promising developments in training people, particularly detectorists, in recording their own archaeological finds on the PAS database. It’s really important to us that the quality of the data is as high as possible but we also want to record as many finds as possible. Technology is changing at such a rapid rate that there’s a good possibility for us to make much more use of technology with the new database to make it easier for the public including finders to help record more archaeological objects and we’re also looking at the strategies for how we record objects.

Angie Bolton, Curator of Archeology, Oxfordshire Museum Service

Oxfordshire Museums locations. Courtesy Angie Bolton.

I’m the curator for archaeology for the Oxfordshire Museum Service and really I’m caring for the archaeology collection. Anything made or shaped by a person with mud on it, if it’s been in the ground, is my area. The oldest objects that I’m caring for are about 200,000 years old and they go through to quite recent times.

The Oxfordshire Museum Service has a museum in Woodstock, Oxfordshire. Our museum service covers the whole county of Oxfordshire and the city of Oxford as well. The museum has got galleries covering the dinosaurs, the Roman period, the Anglo Saxons, even the Victorian period. We also have a good cafe as every museum should. If objects aren’t on display, they’re stored at the Oxfordshire Museums Resource Centre. We have conservation labs with conservators helping us look after our objects. Another building that we care for is a place called Swalcliffe Barn, a medieval barn in the north part of the county, where we store our wagons. We have a YouTube channel, Oxfordshire Museum Service, with a tour of the stores.

I come into the treasure process in the middle, where the report has been written on the items of treasure and we are asked whether we would like these objects for our collections or not. We have certain criteria that we want to meet. My heart says I’d like to acquire everything but in reality we can’t do that.

Oxfordshire Museums facilities and storage and conservation services. Courtesy Angie Bolton.

For example, we need the objects to tell a good story. My slide shows a 5th century silver brooch with gilding on that looks a bit like a butterfly. These are quite rare types of brooches and it’s only the second one that has been found; they are found in female burials. These straddle the Roman and early medieval period – a place that joins schools’ history periods.

It was found by metal detector, not in a known site, and we don’t have evidence of any early medieval activity in the area so there is also research potential. For those reasons it was an object that we really wanted to enhance our collection. On another slide there is a 17th century posy ring which is a gold finger ring inscribed ‘let love endure’ on the inside. That doesn’t have as good or strong a story. We don’t know who owned that ring. There were no initials to give us clues. There’s no makers mark to say where it was made. There’s not as much to say and we see such finger rings quite often coming through the Treasure Act. Although it’s a wonderful object there’s no story behind it so we turned down the object.

The object that’s all wrapped up is in fact a Roman coin hoard found in a parish called Stoke Lyne. It’s the third Roman coin hoard found in this parish, so it’s called Stoke Lyne III. This hoard is still going through the Treasure Act. The finder, a metal detector user, contacted the local archaeologist. It’s been wrapped in bandages but within there is a pot with coins in it that was taken to the British Museum where it was X-rayed. You can see the X-ray with the density of coins at the bottom of the clump and some of the coins going back further. The laboratory then actually excavated or took apart the hoard so they could see where the coins have come from in the different layers. So, we’ve got the research potential, we’ve got a good story because it’s a late 3rd century coin hoard and at the time there was a lot of disquiet on the continent, and you find a lot of coin hoards as a result of that. There’s also research potential because Stoke Lyne doesn’t really have any Roman archaeology otherwise – so why do we now have three hoards being found in this parish?

What Treasure will enhance our collection? Courtesy Angie Bolton.

We consider the condition of the objects too because we are putting these objects on display. There is potential for people to come and look at them and learn their stories, so they need to be in relatively good condition.

Just putting objects on display in the museum isn’t enough. In the case of Stoke Lyne I, another late 3rd century coin hoard of 1296 coins, every one of those coins has been photographed. There is also a Stoke Lyne II coin hoard which was found about 6 feet away. All those coins have been photographed too.

As soon as we could, we put Stoke Lyne I on display in the local library that was nearest to Stoke Lyne so the residents were the first people to get to see it. They held heritage days and Roman coin days at the library and made a big event of it.

We’ve also started to make 3D models of some of the coins. This is a pilot project for people that are partially sighted who learn in a tactile manner. We want to 3D print these coins in a larger size so people can feel the emperor’s heads and the designs on the reverses and see them through their fingers by handling these objects.

What do we do with the acquired Treasure? Courtesy Angie Bolton.

We’ve also put these objects and photos about them on our local heritage search website. This is a website that shows you everything that we have in our collections. You will also find them on the Portable Antiquities Scheme website, but we want them to be accessible to as many people as possible. The objects have been in exhibitions in the museum as well. Even when they come back into storage, people can come and access them through appointment. We sit down with people, and they can look at them a bit closer.

In order to get these treasures into our collections we have to do a lot of fundraising. We rely on the donation boxes, so in every museum you visit you will see a donation box. These are crucial – they really do go towards helping us acquire new objects for our collections. We go to grant funding bodies like the Arts Council England Lottery funding, the Victoria and Albert Purchase Grant Fund, the Heritage Trust Fund and the Friends of the Oxfordshire Museum to raise money. I write to local businesses near where the hoards and the treasure items have been found asking for donations. For example, the Lucy Meakin Ltd. Art advisory service donated money for us to acquire a Roman statue. We do specialist events and lectures: there’s a lot of work that goes into fundraising to enable us to tell these stories and have these objects in a public collection where they’ll stay in perpetuity. It is such a privilege to be able to do this. Treasure is important for the opportunities it gives us.

Randolph Myers, Member of the Board of the Ancient Coin Collectors Guild

The UK Treasure Act and Portable Antiquities Scheme has been an effective means to protect the country’s cultural heritage, and is a less restrictive alternative than for the US to impose import restrictions on ancient coins. Randolph Myers presentation.

I am a volunteer here in the U.S. with the Ancient Coin Collectors Guild, where I’m on the board of directors. We all love and appreciate the history and artistry of the coins and we all volunteer to advocate for coin collecting in the United States. We see the Portable Antiquities Scheme as a model of what countries should consider for the regulation of cultural property and heritage. We advocate before the State Department and the Cultural Property Advisory Committee when MOUs [Memoranda of Understanding] to impose import restrictions have been proposed with foreign countries.

I want to briefly discuss some aspect of American law for our international audience. One of the big issues that the Ancient Coin Collectors Guild has when we look U.S. law is the requirement within the 1983 Cultural Property Implementation Act that before we impose import restrictions, we consider whether there are remedies less drastic than import restrictions. This requirement has not been considered sufficiently in cultural property agreements. The Ancient Coin Collectors Guild has always been an advocate and supporter of how the UK has manages ancient art and coins through its Treasure Act and Portable Antiquities Scheme. This is a far better regulatory method by which the cultural heritage of a nation can be preserved, can be documented, and can be shared with its public and with the world.

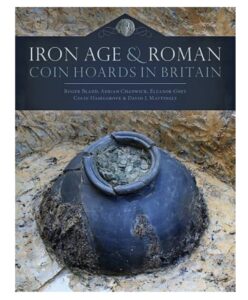

The 2013 UK South Petherton, Somerset, Coin Hoard, “unearthed by a detectorist at South Petherton in November 2013…. and discovered by Mr George Hughes of South Petherton, comprised over 7500 coins. “Mr Hughes and the farmer covered over the area and the farmer stood guard throughout the night until the archaeologist arrived with specialist digging equipment. It took an arduous four days’ work to retrieve it all. The hoard was then taken to London for research and eventually it was released for sale three years later….” Randolph Myers presentation.

As it turns out, I’ve acquired a number of coins which have gone through the UK’s Treasure Act and Portable Antiquities Scheme. I’m showing a coin of probably the shortest reigning Roman emperor whoever existed, an emperor who last whose reign lasted for either days or weeks, by the name of Marius. He reigned in the year 269 and this coin as well as 7500 other coins were found in 2013 at the South Petherton Somerset cohort. In the photograph of that site as it was being professionally excavated, you can see a ring on the top of this coin hoard. You have to wonder, looking back 2000 years, what the people were thinking when they deposited these 7500 coins. Most of these coins of were of this era and slightly beforehand, but one of the coins that was put on top next to that ring was a single coin of the philosopher king Marcus Aurelius. The way in which this hoard was handled demonstrates the type of detailed attention that the UK system provides, in which metal detectorists work with landowners and others to document the discovery of these amazing artifacts. In due course, after the British Museum and local authorities have reviewed a hoard, a number of these coins can be returned to the landowner and finder and thus be available in the market for people who are interested in the history of the period.

The Ancient Coin Collectors Guild has a code of ethics that makes clear that we respect each nation’s cultural heritage and that coins are acquired in the United States in an ethical and legal manner. We not only advocate before the executive and legislative branches, for example giving testimony before the Cultural Property Advisory Committee. I also submit Freedom of Information Act requests about what they’re doing behind the scenes – with different degrees of success.

There are real dangers when source countries claim State ownership of all archaeological objects and penalize finders and collectors. Frankly, this discourages the reporting of finds and stifles the traditional cooperation among academics, dealers and collectors.

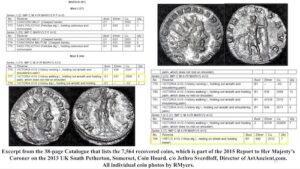

Coin of Marius. Excerpt from the 38-page Catalogue that lists the 7,564 recovered coins, which is part of the 2015 Report to Her Majesty’s Coroner on the 2013 UK South Petherton, Somerset, Coin Hoard. c/o Jethro Sverdloff, Director of ArtAncient.com. All individual coin photos by Randolph Myers.

Among other criteria, the Cultural Property Implementation Act requires that materials restricted from import into the U.S. be of cultural significance and first discovered within and subject to the export control of the State Party, a requirement that can rarely be met in the case of coins.

I want to point out that the Cultural Property Advisory Committee is supposed to be composed of experts in the areas of archaeology, museums, the international sale of cultural property and people representing the interest of the general public. [This committee has to determine whether the country requesting import restriction meets the legal criteria that its cultural heritage is in jeopardy, that the country is doing all it can to halt illicit excavation and trafficking, that it is making efforts to ensure access in the U.S. to its heritage, and that there is no less drastic remedy available than import restrictions.]

We’ve had serious concerns about the composition of the Cultural Property Advisory Committee. It only recently appointed three individuals to fill the seats for members who are supposed to represent the at trade, but for years, the people that were designated as “experts in the trade of art” were no such experts at all. The CPAC committee is supposed to investigate each State Party’s request and seek public comments to ensure that the restrictions comport with American law. We have raised procedural issues because of the lack of adequate notice in order for the public to provide meaningful and timely comments. The most critical failing has to do with whether there are available remedies less drastic than the application of import restrictions – particularly in our case to ancient coinage.

We believe that CPAC should focus in on how well the UK Treasure Act and the Portable Antiquities Scheme work – preserving heritage and at the same time allowing a lawful trade – and recommend the State Parties implement similar legislation.

Finally, I want to highlight the Portable Antiquities Scheme website, where there is an amazing breakdown of all the 7500 coins discovered from this hoard, 81 of which were from that very briefly reigning emperor in 269. The attention to detail that this system in the UK has created is one that we wish other countries would adopt. We at the Ancient Coin Collectors Guild really support your efforts and I hope when the dust settles here we’ll be able to make a significant donation to the Oxfordshire Museum Service so that you can acquire coins from hoards discovered in your region and display them for the benefit of the public.

Sutton Hoo ship burial, donated by landowner to British Museum. Courtesy Michael Lewis.

Sutton Hoo ship burial, donated by landowner to British Museum. Courtesy Michael Lewis.