This story was updated Dec 1, 2020 to include new information on a second deceptive ad campaign produced by UNESCO.

“There is a popular idea that we should have evidence-based policy. The rejoinder is that you often get policy-based evidence. People have decided that something would be a good idea, but then they go running around looking for anecdotes and numbers that back up the policy. If you think that right is on your side, then you are not going to be too careful in scrutinizing claims that fit in with your preconceptions. This is confirmation bias.”

Tim Harford interview, BBC, Zombie Statistics program on cultural heritage and other areas where false statistics dominate, https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/w3cswh1c

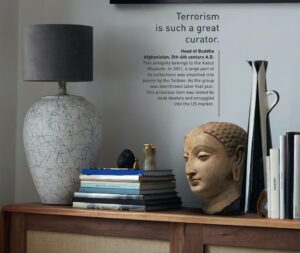

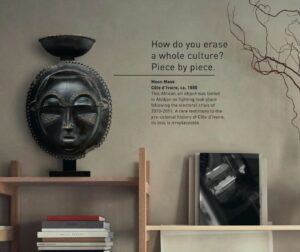

UNESCO celebrated the 50th anniversary of the signing of the 1970 Convention with a public relations campaign alleging that collecting antiquities is a primary cause of heritage loss in recent conflicts, funds terrorism, and promotes the theft of artifacts from museums. UNESCO’s The Real Price of Art campaign showed purportedly looted and stolen antiquities decorating affluent homes. According to UNESCO, the campaign tells the ‘hidden’ story of these objects in order to “reveal the dark truth behind certain works… The other side of the décor… terrorism, illegal excavation, theft from a museum destroyed by war.” The campaign was created by the Paris-based DDB agency and publicized on the internet and UNESCO’s website. The objects used for the campaign were a Palmyran bust of a woman, a ‘moon mask’ from the Ivory Coast, a Gandharan Buddhist head from Afghanistan, a pre-Columbian pot, and a panel from the Ghent Altarpiece by Hubert and Jan van Eyck.

However, except for the van Eyck altarpiece, which was taken from a Belgian museum in 1934, UNESCO’s ‘looted’ objects were not looted or stolen, and the text that accompanied them was a fabrication. The objects photoshopped into these privileged, private settings were actually legally owned artworks belonging to New York’s Metropolitan Museum. They had been acquired in 1901, 1930, and 2015 (this object was in another collection from 1954). The pre-Columbian pot was an Alamy stock image with an equally erroneous text. The last poster depicted a panel from the Ghent Altarpiece by Hubert and Jan van Eyck which actually had been stolen from a museum in Belgium in 1934.

“Terrorism is such a great curator.” On a Buddha head from Afghanistan, in the Met since 1930.

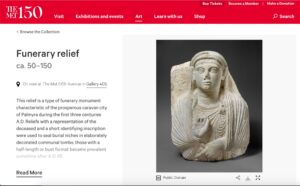

“Supporting an armed conflict has never been so decorative.” On a Palmyran funerary relief, in the Met since 1901.

“How do you erase a whole culture? Piece by piece.” On a Cote d’Ivoire moon mask, provenanced to 1954.

A Buddhist head from the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in NY, photo-shopped into the UNESCO campaign poster with the slogan, “Terrorism is such a great curator.” Stated to have been stolen from the Kabul Museum after 2001. In the Met since 1930.

The campaign text made false claims about terrorist connections to the art market and stated that there is a multi-billion dollar organized criminal trade in illicit artifacts. These accusations do not stand up to even a second of scrutiny. The economic data on which the campaign is based is invented[1] (and the quoted sources actually tell a different story[2]). In fact, all of UNESCO’s claims are contrary to data documented in a major analysis by the RAND Corporation[3] and are belied by World Customs Organization data[4] and other law enforcement reports. The RAND report shows that antiquities crime is actually for the most part ad hoc, opportunistic, and poorly organized, and notes that many, even most objects marketed in the Middle East are likely fakes.

Contrary to UNESCO’s oft-repeated claims that antiquities trafficking comes third or fourth in criminal trafficking, after drugs, weapons, and human trafficking, the World Customs Organization reports that the illegal trade in antiquities represents only a tiny sliver of all criminal trafficking – about 0.2% of the total.

When the Metropolitan Museum became aware of the deceptive use of its images it immediately asked that they be removed from the campaign. The Met makes professional quality photographs of objects in its collections available to the public – but requires that they be correctly credited. Instead, UNESCO framed them within false stories that harm the museum’s image.

The art dealers’ association CINOA filed a formal complaint with UNESCO on November 13, stating that the campaign, “is particularly iniquitous because it sets out to damage the legitimate international art market, not by using evidence to show that it is at fault, as claimed, but by deception. The fact that such deception was deemed necessary or even desirable could be interpreted as another demonstration UNESCO lacks the evidence and examples to support its claims.”

CINOA which represents over 5000 art dealers from professional organizations around the world, has been active for years in building a responsible art market, providing accurate data on the trade, and challenging false information circulating among European and US legislators. It has worked for years, despite repeated denial of access to meaningful discussions, to give the art trade a voice within UNESCO, the European Commission, and national and EU legislatures and cultural ministries. Regarding UNESCO’s The Real Price of Art campaign, CINOA’s president Clinton Howell issued a letter on November 10, 2020, in part congratulating UNESCO for its positive work to preserve heritage, but asking,

“Why does UNESCO continue to cite inflated and unfounded claims regarding the size of the illicit trade in cultural property and keep the legitimate trade at arms-length? This comportment damages the interests of the art trade and collectors. It also risks the credibility of UNESCO’s authority in this crucial area of activity, especially when the inaccuracy of these figures is so easy to show. For example, it takes only a few minutes to demonstrate that the $10 billion headline figure UNESCO is using for its anniversary campaign, The Real Price of Art, is bogus. What’s worse, UNESCO was warned of this issue three weeks ago, yet still holds to the figure publicly. Of equal concern is that such claims are being made by senior UNESCO officials.”

CINOA urged the establishment of an international forum under UNESCO and UNIDROIT bringing together the art market, law enforcement and collectors to work together to use accurate data and factual information in the fight against the illicit trade. See the full November 10, 2020 letter here.

And here, the November 13, LINK TO CINOA’S FORMAL LETTER OF COMPLAINT REGARDING UNESCO CAMPAIGN

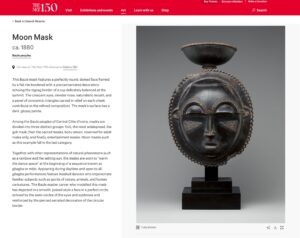

A moon mask from the Ivory Coast whose provenance dates back to 1954 and was acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2015. Unesco erroneously describes it in an advertising campaign as having been looted in Abidjan after an electoral crisis in 2010-11.

UNESCO has since deleted the pages showing the Metropolitan Museum images from its website. Its publicists have photo-shopped different objects into each “collector” home to create new posters, but UNESCO’s statement only expresses regret for its use of the museum’s artworks, not for the false statements it made regarding their origin. Nor does UNESCO admit anywhere that its numbers are unsubstantiated and its claims that the art market is funding terrorists are not supported by any evidence and have long since been dismissed by reputable analysts.

The UNESCO publicists’ disdain for the interests of museums is clear in the fact that they felt free to portray artworks long in museums and legitimately acquired as looted. (ICOM, the International Council of Museums likewise creates its Red List of ‘typically looted objects’ using images of artworks in museum collections although it at least acknowledges the source of the objects.) Such maneuvers are not an honest attempt by UNESCO to come clean, much less to defend the accuracy of its evidence-free claims about the art market.

When it was caught, UNESCO backed off.

When news of the faked publicity campaign became public, UNESCO published a statement half-apologizing for telling a false story using Metropolitan Museum images:

“In an initial version of UNESCO’s campaign, the ‘Real Price of Art’, some posters displayed items from the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MET) database, which is in the public domain. UNESCO’s intention was to alert the general public by depicting objects of high cultural value, which should be on display in museums, presented in luxurious private interiors. UNESCO had no intention of questioning the provenance of items in the MET collection… UNESCO regrets the use of MET images that caused any misunderstanding.”

UNESCO continued to justify the publicity campaign as, “encouraging [the public] to exercise due diligence when purchasing cultural property.” UNESCO also failed to completely remove the campaign from the Internet, still seen here on December 1.

Then UNESCO lied again, replacing the MET images with MORE false stories.

A new ad was produced using a tribal mask that UNESCO states was stolen in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire during internal fighting after an elections crisis. An investigation by the International Association of Dealers in Ancient Art and CINOA discovered that this was also false, after the Director of the museum from which it was supposedly taken confirmed in an email that the museum still possessed it.

A second replacement ad showed an alabaster figure of a woman wearing a polos. The ad claimed it was a “priceless antiquity taken from the National Museum of Aleppo” in 2014 and smuggled into the European market. In fact, it was an image available in stock photo archives. For purposes of the ad the statuette was made to look larger and its image was reversed.

The statuette is still in the National Museum of Aleppo. It can be seen in a video celebrating the reopening of the Aleppo Museum in late 2019 (seen at the far end of a case at 1.24 minutes ). IADAA also found contradictory statements in another video regarding claims it had been stolen.

In this video, the Director of Aleppo Museums and Antiquities, Khaled Al-Masri, states that

“During the crisis the museums was under a fierce attack of armed gangs which directly targeted the museum with different types of mortars and missiles… nevertheless, its entire antiquities were saved thanks to the Syrian Arab Army efforts along with the museum’s employees who kept such antiquities safe.”

There are fundamental flaws in UNESCO’s focus on blaming the art trade for looting and archeological loss.

Why does UNESCO continue to lie? Instead of focusing on larger causes of heritage loss such as urbanization, building of roads, dams and infrastructure development, UNESCO has placed blame for heritage destruction almost exclusively on illegal art trafficking.

It is true that in 1970, when the UNESCO Convention was opened for signature, archaeological looting was rampant – both by subsistence diggers and professionals. The 1970s and 1980s saw hundreds of archaeological sites across the world pilfered and many thousands of objects exported from source countries without permission – albeit with the connivance of local officials.

However, together with the rest of the public, Western museums, art dealers, and collectors have learned from this appalling destruction and changed their buying habits. Most art dealers have long since adopted due diligence practices to weed out looted materials and refuse offers of suspect goods. Dealer organizations such as ATADA in the US prohibit members from trading in illegally sourced or sacred objects. The IADAA and others have imposed self-regulatory standards that prohibit dealing in objects from conflict zones. The Responsible Art Market initiative has established scaled standards for large and small art businesses.

Moon Mask, acquired by the Met in 2015 from a collection extant since 1954, Screenshot of catalog of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY.

Unfortunately, archaeological destruction continues apace, but now the culprit is often a corporate entity seeking land use or a government project for infrastructure development. Peruvian archaeologist and former Minister of Culture Dr. Luis Jaime Castillo lamented in a recent presentation that it is harder to fight lawyers than looters. While noting that archaeologists are ill equipped to fight with organized crime, and arguing for additional efforts to curtail sales to end consumers, he also said:

“For people in the Americas and many parts of the developing world, looting is not anymore the issue. It might have been in the 19th century, or in the early 20th century. Today, the biggest problem we have is land encroachment and land trafficking. The development of cities and the new technologies used for agriculture are finally stepping into territories and sites that have never been affected before. That is 99% of our issues regarding archaeological heritage. One percent is looting. Because now, rather than destroying one burial, or two or ten or twenty, we are destroying entire sites. A bulldozer is coming in and bulldozing tens of hectares and developing that into agricultural land or developing that into cities…”

“Those are the real issues. Of course, one of the ways to blockade the land is to loot it and then pass in the bulldozers. In the past, when we had to face looters, we had to face basically a peasant with a shovel. Today we have to face lawyers – a bunch of lawyers that are going to protect with all the legal schemes that you can imagine the people that encroach and take over the land…”

“If you have one hectare of land, that is ten thousand square meters. If each meter is worth $10, we have $100,000 there in wealth. If it is $100 per square meter, that is one million dollars. And here in Peru, for one million dollars, people kill you. Those are the issues we are facing… because things are changing, we have to adapt to different settings and different motives.”[5]

Despite its contemplation in the 1970 Convention, UNESCO has never promoted permitting systems.

Head of Buddha, Afghanistan, possibly Hadda. Acquired by the Met in 1930. Screenshot of catalog of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY.

UNESCO is not interested in adaptation or new models. UNESCO and other international organizations persist in dividing all art in circulation into ‘legitimate” or ‘illicit’ categories based upon whether it was accompanied by an export permit from its source country. An artwork in a country outside its origin should not be automatically suspect of illegality, nor does owning an artwork from another country indicate wrongdoing.

Since few signatory nations to the 1970 UNESCO Convention ever created permitting system for art exports but instead chose to nationalize all antiques, UNESCO is well-aware that making this a condition for legal trade sets an unreasonable standard. This is especially the case because importation of artworks into Europe and the U.S. without such permits has been and remains legal today in most cases.

Art world organizations have pointed out that the argument that only ‘permitted’ objects should now be deemed legal is a red herring – it results in automatically categorizing the vast majority of artworks in museums and in the market as ‘illicit’. Because of this impossible-to-meet standard, only artworks with documentation prior to 1970 – fifty years ago – are considered relatively ‘safe’ in the market. Because importing did not require those documents, when export documents could be obtained, there was no legal reason to retain them for fifty years or more.

UNESCO has rejected viable regulatory solutions, preferring draconian measures that would end the art trade.

Art organizations argue that in these circumstances, legislation that automatically makes all objects without documentation illegal to trade will eliminate a lawful art market, taking the legitimate art dealers, the ‘good guys,’ out of business and pushing the far smaller illegal market underground.

Instead, realistic documentation programs should be put in place based upon a more sensible threshold to ensure that newly looted objects cannot be sold. If a primary goal is to halt looting, artworks collected before a certain date (for example 2014, when ISIS gained prominence), could be documented with digital data and images. Recently looted artworks could not be traded because they would lack documentation to qualify.

The art market broadly supports the creation of systems that would enable the circulation of documented art and artifacts, but UNESCO has never even engaged in discussions around this solution. Yet such a system is not only viable, given today’s technology, but is likely to be successful. Collectors would gladly pay a premium for documented works and the legal certainty they would provide. To take just one example of how the market has changed, other things being equal, a provenanced work with an ownership history going back to the 1990’s has significantly more value than an artwork that lacks documentation.

Combined with a system like the UK’s Portable Antiquities Scheme, which rewards finders who report discoveries, this could protect heritage sites, disincentive looting, and create a safe space for collectors and museums by enabling a lawful trade in objects already in circulation.

UNESCO’s disinterest in meeting with the actual experts in the art trade – the trade itself – is concerning. It appears that not only does UNESCO’s bureaucracy deny the value of accurate data on criminal activities – it has not bothered to learn basic facts about the legitimate trade.

Why does UNESCO continue to knowingly repeat falsehoods?

What UNESCO is doing in this campaign is estimating the numbers of a crime that has not been reported. The numbers given for the illegal trade are so high that any journalist in search of scandal will gravitate to it despite the lack of evidence. Dr. Fiona Rose-Greenland headed a University of Chicago “Modeling the Antiquities Trade in Iraq and Syria (“MANTIS”) Program[6] that monitored satellite images of Syria and Iraq to track trafficked artifacts, and which found in preliminary reports that ISIS was likely to have only earned around $4 million in profits in total—a “far cry from the $7 billion” initially reported. Why, the difference? According to the MANTIS team leader Dr. Fiona Rose-Greenland, “[i]t’s a lot easier to call for action against a $7 billion crime than a $4 million one.”[7]

Specialists studying how data on crime is perceived have stated that the higher a number is, the more likely it is to be used and repeated, but it is also more likely to be false. When you go back to try to find it, it is also more likely to be taken out of context.[8]

In the case of a large bureaucracy such as UNESCO, which works within long-term partnerships with other large bureaucracies and multi-national organizations, one reason that false claims gain credence is that they reverberate in a sort of echo chamber of inter-organizational repetition. Take, for example, UNESCO’s frequent repetition of a statement that appeared on International Criminal Police Organization’s (INTERPOL’s) website more than a decade ago that the trade in illicit cultural property was the third largest illegal market after drugs and weapons – even though Interpol removed it a decade ago and now says that there is not sufficient data to support an estimate.

As the RAND report states,

“no governmental or international body maintains comprehensive statistics on the global antiquities trade…” Despite pressure from Interpol’s Expert Group on Stolen Property for better data gathering and systematic research, “it remains impossible, to this day, to precisely rank illicit traffic in cultural objects so as to measure it to other types of transnational crimes.”[9]

People and organizations hold on hard to their preconceived notions and UNESCO seems unwilling to accept the idea that if you can’t find evidence for something, maybe it isn’t there. UNESCO policies are based on confirmation bias – they want to see crime so badly that they insist that it must be there, just very, very cleverly hidden.

It is a bad choice to rely on unverifiable sources for making policy and to use selective examples that fit your argument to make generalized claims. It is outrageous that a respected institution like UNESCO continues to use wildly exaggerated numbers and phony data to delegitimize museums and the art trade. The art trade and collectors agree that any actually stolen objects should be identified and returned. But no one and no organization has the right to claim that any – or as some say –almost every object is stolen without evidence. The activists leading this effort know the law. They should know better than to throw out such reckless accusations.

Conflict of interest is a key reason why UNESCO cannot come clean.

UNESCO’s exclusive focus on state to state diplomatic and ministerial relations means that criticism of governments that themselves target cultural heritage is muted when it occurs at all.

Money also matters. The most egregious example of this is UNESCO’s complete failure to mount a campaign against one of the greatest human rights and cultural tragedies of our time, the deliberate destruction of Uyghur culture and identity by the government of the Peoples Republic of China, a major funder of UNESCO.

It is targeting art dealers instead.

What UNESCO has done – and not done to meet the goals of the 1970 Convention.

Funerary relief thought to be from Palmyra dated from 50-150 CE. Screenshot of catalog of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY.

The primary result of the 1970 UNESCO Convention has been the enactment of all-encompassing export restrictions and laws making artistic works and historical property, usually including documents, photographs, prints, paintings, sculptures, manuscripts, books, stamps, coins, scientific specimens and “ethnic art” more than 100 – and in some cases only 50 years old – the exclusive property of national governments.

UNESCO has done nothing to encourage member states to establish permitting systems for exports of objects of lesser value or historical importance in order to enable a lawful, documented trade in art and artifacts across the globe, as envisioned by the original document. It has failed to motivate its member nations to fund the protection of sites and preservation of monuments, or to build museums for their own citizens. And while many nations that adopted blanket export prohibitions did create legislative exceptions for export for scientific purposes and museum loans, UNESCO has not exerted itself to insist that members set reasonable rules for museum loans or adopt immunity from seizure laws that would allow U.S. and European museums to make long term loans of objects back to source nations.

This is a far cry from what UNESCO aspired to be.

UNESCO and the Hague Convention had promised to build international acceptance of a higher duty to shield monuments, cultural heritage, scientific and academic knowledge in war and internal conflict. Unfortunately, UNESCO has largely failed in its efforts to mitigate damage in war. Despite decades of international agreements to protect monuments and educational, scientific and cultural institutions, national governments have continued to target civilian cultural institutions and historic sites. Only a few nations have created systems for safe harbor of objects at risk.

UNESCO has failed to apply pressure to national governments to adequately fund preservation of monuments and to build national cultural systems, halt loss of archaeological resources, or to prioritize preservation while developing economic infrastructure.

UNESCO has failed to act effectively to protect the human and cultural rights of citizens from abuse by their own governments; it has been too cowardly to take a stand in defense of religious rights and rights of free expression when its member states abuse them.

UNESCO has failed to address national government policies persecuting minorities – from actual genocidal policies against Uyghurs in China, to anti-Islamic policies in India, anti-Semitic and anti-Christian policies in Turkey.

Instead, UNESCO has focused on the weakest target by discrediting art dealers, collectors and museums with false claims intended to sow distrust and undermine the legitimate circulation of art. What will the consequences be? These destructive accusations may ultimately lead to an end of the legal trade in ethnographic art and antiquities and to fewer people supporting museums. Perhaps that’s ultimately the goal of these baseless claims.

[1] Lazare Eloundou Assomo, Director of Culture and Emergencies for UNESCO’s Culture Sector, was interviewed on “Antiquités du sang”, quand pillage et pandémie font bon ménage!” on Radio France Culture on October 24, 2020, during which he said the value of the global trade in illicit antiquities alone was estimated at $64 billion. The Art Basel Report, the leading world art market report, estimated in 2019 that the value of the entire global art market was $67.4 billion, and the legitimate market in Middle East and North African antiquities is around 0.5% of this. In another interview on BBC World Services’ Business Daily special Zombie Statistics on February 20, 2019, Assomo was challenged regarding UNESCO’s repeated use of inaccurate figures for illegal trade, to which he responded, “I don’t think we should enter into a debate about whether these figures are right or not right,” while at the same time asserting that looting had increased. Interview, BBC, Zombie Statistics program on cultural heritage and other areas where false statistics dominate, https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/w3cswh1c

[2] The IADAA tracked down the supposed source, the 2018 Joint European Commission-UNESCO Project report, Engaging the European Art Market in the fight against the illicit trafficking of cultural property, by Professor Marc-Andre Renold, which gave a lower but equally preposterous number, and cited another article, in which the author simply stated that the numbers were “regularly given,” without supporting evidence.

[3] Matthew Sargent, James V. Marrone, Alexandra Evans, Bilyana Lilly, Erik Nemeth, Stephen Dalzell, Tracking and Disrupting the Illicit Antiquities Trade with Open Source Data, The RAND Corporation, 2020 (hereafter RAND)

[4] Similar false statements have been made repeatedly – and never supported with evidence – for the last 20 years. Interpol, the original source for a statement speculating that antiquities could be third in volume after drugs and arms, withdrew this assertion from its website more than a decade ago, and now makes no such assertion. Despite such claims being widely recognized as completely untenable, an autumn 2020 editorial in The UNESCO Courier by Ernesto Ottone Ramírez, Assistant Director-General for Culture, UNESCO, states it as fact.

[5] Antiquities Coalition debate, Do Archaeologists Have an Ethical Obligation to Report Looting? 22:45-25:25 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E2nwMxkROgk&feature=emb_logo

[6] Modeling the Antiquities Trade in Iraq and Syria (MANTIS), University of Chicago, https://oi.uchicago.edu/research/projects/mantis

[7] Fiona Rose-Greenland, Inside ISIS’ looted antiquities trade, The Conversation, May 30, 2016, http://theconversation.com/inside-isis-looted-antiquities-trade-59287

[8] Kathryn Moeller of Stanford University, interview, BBC, Zombie Statistics program on cultural heritage and other areas where false statistics dominate, https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/w3cswh1c

[9] RAND, at 8-9, quoting Frances Desmarais, “An International Observatory on Illicit Traffic in Cultural Goods,” in Frances Desmarais, ed., Countering Illicit Trade in Cultural Goods, Paris: International Council of Museums, 2015.

Cultural Property News expresses its appreciation to the diligent researchers from CINOA and the IADAA who uncovered this story and generously shared sources and information.

Image from UNESCO's The Real Price of Art campaign, which misrepresented legitimate objects as "stolen." A funerary relief thought to be from Palmyra is photoshopped into a private setting. The ad text says that it was stolen from the National Museum of Palmyra by Islamic State militants, but the Metropolitan Museum of Art reports that it acquired the object in 1901.

Image from UNESCO's The Real Price of Art campaign, which misrepresented legitimate objects as "stolen." A funerary relief thought to be from Palmyra is photoshopped into a private setting. The ad text says that it was stolen from the National Museum of Palmyra by Islamic State militants, but the Metropolitan Museum of Art reports that it acquired the object in 1901.