When Ottoman Turks breached the walls of Constantinople on 29 May 1453, the first Christian shrine to fall was not Hagia Sophia but the Chora Monastery, which lay close to the Adrianople Gate. Entering the church, soldiers found the venerated icon of the Virgin Mary, which was once paraded along the walls to provide spiritual protection for the city. They cut the icon to pieces. But they were not interested in diffusing its miraculous powers (as we might imagine), they were simply dividing up its silver cover as booty. They seem to have completely ignored the rich program of mosaics and frescoes that decorated the church.

In this, they were not alone. Long after the church was converted to a mosque – sometime before 1511, and subsequently known as the Kariye Camii – its rich interior decoration was left intact. Stefan Gerlach, a German ambassador, visited the mosque in the late 16th century and described the painted decoration in detail, noting only that a few faces, close to the viewer, had been scratched away.

Out of the city center and well off the beaten track, the building and its rich Byzantine decorations survived the Ottoman centuries in obscurity. Rediscovered with the advent of Western tourism, the Kariye became known as the “Mosaic Mosque” for its rich program of mosaics still uncovered – a must-see stop on the touristic itinerary, before visiting the dancing dervishes.

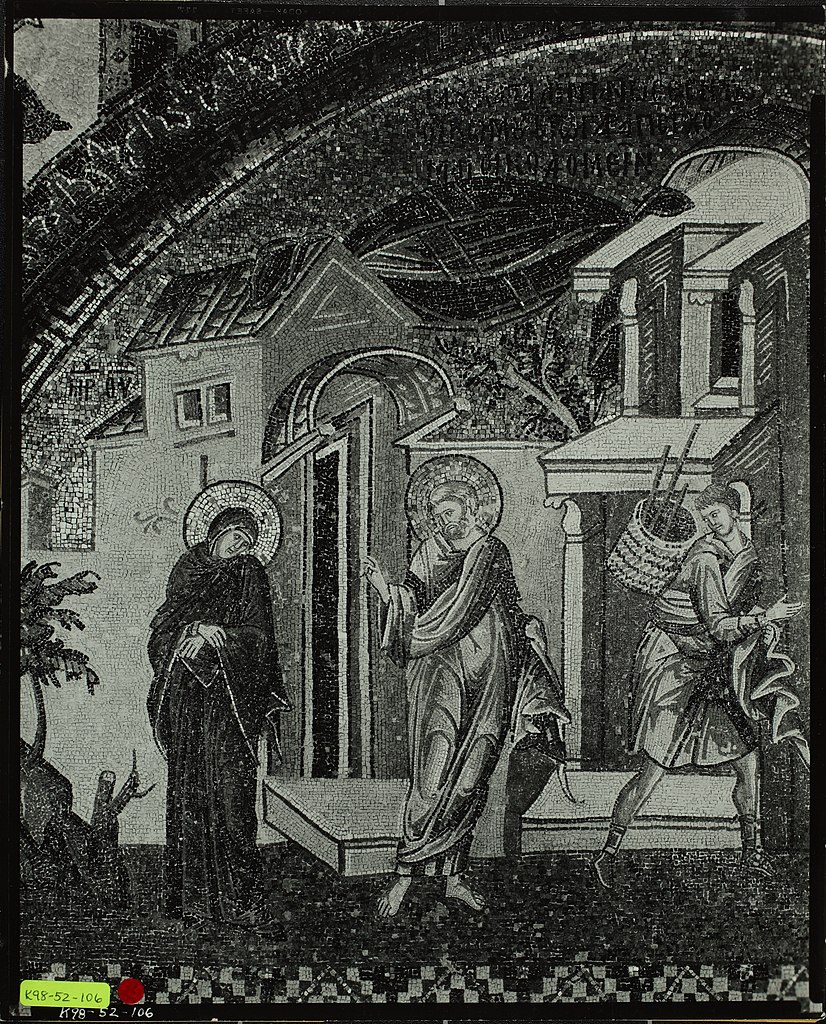

By the mid 20th century, the mosque was virtually abandoned and falling to pieces. Converted to a museum in 1945, the building and its abundant decorations were lovingly restored by the Byzantine Institute of America and the Dumbarton Oaks Field Committee, 1948-58. Today the museum is one of the most popular in Istanbul. Its mosaics bristle with beauty and elegance – all thanks to its knowledgeable and involved patron, Theodore Metochites, prime minister of the Byzantine Empire in the early decades of the 14th century and the greatest intellectual of his age. He provided both “hothouse conditions” for the artisans, as well as an unlimited budget. The surviving mosaics are complemented by extensive cladding in colored marbles and a brilliantly frescoed funeral chapel – the latter uncovered in pristine condition in the 1950s. Not only is the art of the highest quality, it represents the most extensive Byzantine decorative program to survive in Istanbul – justly compared to the contemporary artistry of Giotto or Duccio in Italy.

Unlike the Hagia Sophia, which has been very much in the news because of its conversion from a museum to a mosque last month, the Kariye never held a significant political role during the Ottoman period – it survived in obscurity. No important events took place there; no one important was buried there.

Thus, it confounded everyone when on 21 August, President Erdogan announced that the Kariye Museum would be reopened as a mosque. There is no historical rationale for this, and no call to conversion. Its transformation makes no sense at all – except that it represents the last of the Byzantine churches converted to mosques and subsequently to museums in the city. Rather than reclaiming an important historical artifact of the Ottoman period – as one might argue with Hagia Sophia, the re-conversion of the Kariye represents no less than a blatant attempt to erase Istanbul’s rich Byzantine heritage.

It is worth remembering that the Byzantine Empire no longer exists. 1453 marked the end of it. One wonders why Mr. Erdogan continues to fight a battle the Ottoman Turks won more than half a millennium ago, rather than address the more crucial problems his country now faces.

Robert G. Ousterhout is Professor Emeritus at the University of Pennsylvania and a specialist in Byzantine architecture. He is author of Eastern Medieval Architecture: The Building Traditions of Byzantium and Neighboring Lands (Oxford 2019).

Kariye Camii, Joseph Taking Leave of the Virgin and Joseph Reproaching the Virgin Mosaic, Istanbul, Turkey - Entire view of both scenes and partial view of surrounding scenes, photo 1952, Byzantine Institute and Dumbarton Oaks fieldwork records and papers, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, DC Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

Kariye Camii, Joseph Taking Leave of the Virgin and Joseph Reproaching the Virgin Mosaic, Istanbul, Turkey - Entire view of both scenes and partial view of surrounding scenes, photo 1952, Byzantine Institute and Dumbarton Oaks fieldwork records and papers, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, DC Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.