Hartwig Fischer © Benedict Johnson.

The Committee for Cultural Policy and Cultural Property News present for public access an important essay by Hartwig Fischer, Director of the British Museum. The essay sets forth new goals for the British Museum and outlines frameworks for dialogue and collaboration between the Museum and the peoples of many different cultural backgrounds that have contributed to its collections. Our thanks to the British Museum and to the authors of its initial publication: Kunst & Recht 2019 / Art & Law 2019: Referate zur gleichnamigen Veranstaltung der Juristischen Fakultät der Universität Basel vom 14. Juni 2019 (Schriftenreihe Kultur & Recht Book 11), by Peter Mosimann and Beat Schönenberger. Copyright Hartwig Fischer, Director, The British Museum.

Collections entail responsibilities. Notes on a global institution.

1. Cultural resources

In his essay ‘There is no cultural identity’, published in 2016,[1] the French philosopher and sinologist François Jullien reexamines the concept of the universal––as developed and advanced by the West. Jullien considers the challenges the concept increasingly faces as new centres of power and thinking emerge, Western controls mutate or wane, globalisation diversifies or fractures, nationalisms thrive, and reclamations abound. Without reducing universalism to a mere tool of domination––its roots and development over 2500 years are diverse and complex––Jullien states that any claims to a (totalising) universal, on the part of the West, are no longer sustainable. In its place he advocates a ‘rebellious universal’ which, as an unattainable horizon, an unachievable ideal, keeps us searching, keeps peoples from retreating into their ‘cultural differences’, from indulging in their ‘essence’; instead it pushes them to continue facing and reaching out towards each other, and to continue developing and transforming, an attitude which alone keeps them alive.

Opposing the concept of difference defining identity through exclusion, Jullien strengthens the notion of écarts, a distance, or inbetween that connects. Jullien insists that cultures are interrelated through an inbetween that keeps them en regard, in sight of each other, each remaining dependent on the other, challenged by the other. Through the inbetween that keeps them linked, each culture activates the other as a resource, pushing each beyond the boundaries of its ‘identity’ and opening them up to the impact of the other. We should conceive of culture here as a set of thought systems, beliefs, and interactions growing out of history, a people’s or group’s practice, knowledge and conceptions that develop over time, through the accumulation of individual and collective actions and interactions.

What bridges the distance between cultures and enables us to use them as a resource is dialogue, a dialogue that respects the otherness of the other and enables us to comprehend ourselves, and the other, in our interconnectedness.

Jullien’s ‘dialogue’ combines dia, meaning distance as well as moving across the distance, and logos, meaning the possibility of understanding, the shared common ground of intelligibility.

Jullien fears that the West has put its ability to dialogue at risk. With the overpowering strength of its ‘global’ values it has tried to impose its universalism on other peoples, colonising their cultural practices through triumphant rationality, which in turn is now provoking identity claims whose virulence mirrors the uniformity formerly imposed by the West.

A true dialogue can only take place in the language of both cultures, Jullien claims, between languages: translation is the basic, practical implementation of dialogue, it reveals the discomfort, the permanent disquiet, the nondefinitive nature of any authentic dialogue, moving forward through neverending reiterations. It also reveals its strength: moving between cultures and bridging the écart generates energy and engagement, leading to mutual understanding.

Jullien’s thinking addresses important aspects of what the British Museum as one of the great comprehensive institutions of human cultural achievements aspires to: a selfcritical but confident universalism constantly engaged in dialogue to activate its collection as a beneficial cultural resource for millions of people. This resource should be available physically both in London and abroad, and digitally across the world, working with specialists and communities from all continents to bring out the many stories the objects in its care encapsulate, rendering them meaningful and accessible for a most diverse global public. The Museum itself has the capability to constitute a ‘shared common ground of intelligibility’––each object in its collection has the potential to generate dialogue.

All human societies create material circumstances within which people live and attempt to thrive. Such material circumstances are embodied in the artefacts in the British Museum, which are concrete instances of the logics, emotions, aesthetics, successes and failures of all human ways of life. Living in a multicultural world involves bringing one’s own logic into contact with other logics and exploring areas of congruence and disjuncture. The Museum is the very place of hospitality to allow this to happen, to acknowledge areas of similarity, and also of radical difference in engaging with the cultures of the world.

But isn’t the Museum’s claim to universal relevance being challenged by movements in many parts of the world that reject cosmopolitan approaches in favour of nationalist and populist ideologies, denounce universalism as self-interested subterfuge and endorse the renationalisation of cultural politics? What is the Museum’s position in the current debate ‘about possession of objects and sites, about who is entitled to produce knowledge and narratives about them, about the contexts in which they are most appropriately understood and accessed, and about who is responsible for their conservation and preservation’, to borrow Professor Sunil Khilnani’s succinct formulation during a recent conversation.

2. A collection belonging to the world

The British Museum Court and Glass Dome, Photo Eric Pouhier.

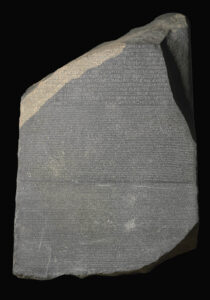

The British Museum is a unique place of translation, placing cultures in sight of each other, bridging the écart and making them freely accessible. It is no coincidence that the most visited object of the Museum is the Rosetta stone, the one object that, discovered and transferred from Egypt in a context of imperial competition, allowed Champollion and his contemporaries to decipher the hieroglyphs and thus rediscover and open up the history and culture of ancient Egypt.

The British Museum was founded in 1753 when Britain was already a significant power with colonial possessions across the world. This context is obviously important to the history and character of the collection of the British Museum. But the Museum was not established as an arm of the state to celebrate British imperial power. It was founded at the height of the European Enlightenment by the British Parliament as an independent charitable trust. Its collection had to represent the world; it had to be kept together forever, for the benefit of present and future generations; it had to be openly accessible for everybody, for people from all nations, not only the British; the collection had to be explored through innovative research bringing together different disciplines to compare cultures across the millennia and to understand our common humanity; and the knowledge thus generated had to be widely shared to benefit the public. In other words, the Museum was meant to be not only about objects and the knowledge and stories they preserve but just as much about relationships and exchange between human beings.

In order to deliver these objectives, Parliament vested responsibility for the institution in the Trustees. The Trustees have fiduciary ownership of the collection, but they are owners only inasmuch as they act on behalf of the entirety of its beneficiaries, and these beneficiaries, or owners, are the citizens of this world, and future generations.

This is a unique setup: It has created an exceptional tool to study and explore the history of humankind through significant objects, from first beginnings until today.[2]

3. Colonialism, Imperialism

The term colonialism’ refers to nations or powers or elites extending their authority over territories and peoples, primarily for the purposes of expanding trade and accessing and using resources, mostly to the benefit of some parts of the population, and to the disadvantage of others. There are evidently great differences between the basic types of colonialism that variegate into a great range of forms impacting on the identities of all involved whatever their role and position within these constellations.

There are vast differences, also, between the loose network of Greek or Phoenician cities across the Mediterranean and centralised, industrialised states that carve up an entire continent, Africa, into different areas of rule and exploitation, or between the Empires of the Aztecs and the Empire of Han China.

Broadly speaking, however, we might say that colonialism and its specific form of government, Empire, have marked the last 5000 years of history, and have for a great number of people provided the basic political and social framework of their lives: ‘An empire is thought to exist where there is some overarching political control over subject colonies. Imperialism is a special case of colonialism where there are colonies tied together into one political structure, which has a series of ideological, economic and cultural implications’, Chris Gosden writes in Archaeology and Colonialism.[3]

Empires and colonialism themselves are part of the global history of power, inequality, and exploitation, the history of amassing resources for major innovations and developments that have shaped the world, its societies, and individuals and their notions of both society and identity profoundly. The emergence of the modern world and of globalisation as a world system are marked by colonialism. ‘Colonialism is the major cultural and historical fact of the last 500 years and to some extent the last 5000 years’, Gosden writes.[4]

‘Colonialism is a process by which things shape people, rather than the reverse. Colonialism exists where material culture moves people, both culturally and physically, leading them to expand geographically, to accept new material forms and to set up power structures around a desire for material culture.’[5] We understand the experience of people living under the conditions of colonialism through the items they made, exchanged, used, had to give up or left behind. A considerable number of objects in the collection of the Museum are themselves documents of forms of imperial rule and colonisation dating back over 5000 years, through many different forms of Empire across the world. They allow us to situate colonialism within the long history of empires as a political and cultural phenomenon and their crucial role in the diffusion and displacement of people, ideas, cultural practices and things on the one hand, of exploitation, oppression and destruction on the other, with slavery as its most horrendous and pernicious practice.

However, the imperialism and colonialism that the current debate on restitution focuses on is the more recent form of this type of rule. It is still close to us, it marks the lives of people up to the present, and it is part of our own past even though we were not directly involved in it or not even born when it ended. It is a shared difficult past. Acts of violence were perpetrated during the period of imperial conquest and during colonial rule with effects that echo into the present. Institutions like the British Museum have a responsibility to address and respond to these challenges.

4. Restitution

The report on the return of objects to Africa commissioned by President Macron, written by Felwine Sarr and Bénédicte Savoy and published in November 2018[6] advances two areas of action: restitution, and collaboration, following the President’s earlier statements on colonialism as crime against humanity (in February 2017 while campaigning in Algiers) and on the temporary or permanent return of African objects in French public collections (in a speech in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, in November 2017).

In assessing how objects have entered collections in France, the authors make the basic assumption––following Macron’s assertion––that colonialism constitutes a crime against humanity and that therefore any transfer of objects under the conditions of colonialism was inherently illegal, unless the present owner can prove that an object was acquired with the full and documented consent of the previous owner, and that an adequate price was paid. They suggest that the major part of African holdings in France (and by implication in Europe) should be returned, or rather that they are still the property of nations, communities, institutions or individuals in Africa, and that it was France’s duty to acknowledge this fact, and the African states’ only task is to decide at which moment over the next decades they would take back the objects or leave them as loans in European museums. Nations, communities, institutions or individuals are here being subsumed by and represented through the state, and not acting on their own behalf––a legal and political assumption with farreaching implications. The authors of the report consider other forms of collaboration as inadequate and basically unacceptable unless the objects have been returned at least in principle. The return alone corroborates the acknowledgement of past wrongs and the intention to engage in a process that would heal the wounds inflicted by European colonialism.

Sarr and Savoy argue that return is an indispensable prerequisite of more beneficial, more equitable relations between Africa and Europe, in a crucial moment of economic and intellectual transformation that will lead African nations to decide for themselves what kind of society they want to build, what kind of economy they want to develop, how to interpret and come to terms with their own complex past, and how to engage with the rest of the world.[7]

5. Engaging with the world

While convinced that the foundational value of the British Museum’s collection––and its global significance––resides in its breadth, depth, complexity and unity, the Museum has been working with communities and institutions across the globe, entering into difficult conversations about the past, and charting together a course that provides access to objects, tells their stories, makes different voices audible and uses them to reconnect with the past and derive from that connection new energies to shape the future.

The research conducted by the British Museum in partnership with others frequently reveals how layered, differentiated, entangled a historical situation can be when it comes to agency in trade and transfer under the conditions of colonialism in the British Empire, but equally across continents and millennia. This too needs to be acknowledged, and so indeed should the role of power, inequality and exploitation on all continents throughout history. There is no obvious reason for limiting this debate to any specific region, and the British Museum never has. Nor is there a reason to limit it to the late 19th and early 20th century or solely to European empires. The same arguments can apply to all countries formerly under colonial rule or simply under the rule of someone else. Colonialism and imperial expansion have been practised on most continents, and long before European states rose to global power.

When does a region (or community) cease to be independent and turn into an integral part of a bigger whole, and inversely when does it gain independence and turn into an entity in its own right? Obviously, identities are multiple at all moments, and they are constantly in flux. Objects do not necessarily have a national identity inscribed into them and aligned with present-day nations and territories. In what sense can modern nation states lay claim to historical objects that predate contemporary national delineations and sentiment? Objects frequently carry intricate legacies of transfer and acquisition, involving violence, conflict and inequality long before they enter a museum.[8]

In addressing these questions and in trying to chart an answer the British Museum must be aware of the persistence or recalibration of colonial structures today and their political, economic, social, and cultural dimensions in regional, national and transnational contexts. The shifting centres of power and of power constellations reshape the way we negotiate the specific relationship between the individual and local on the one hand, and the pervasive nature of global connections on the other. There are few places that allow us to engage in these processes like the British Museum, within the reference frame of two million years of human development in its diversity, complexity and unity. ‘To understand the present in its unique form, and its historical lineages, we need to understand the past shapes that colonialism and power have taken through material culture. The past histories of colonialism are no infallible guides to grasping the present, but they can open up our minds to the range of possible shapes power takes, which will provide inspiration in understanding our present situation and for seeking a more human dimension to global structures.’[9]

The British Museum has made great efforts in seeking to contribute to ‘a more human dimension to global structures’ by making the collection ever more accessible as a means of learning and knowledge. Its curators work with communities from around the world every day, and conduct research on the history of its collection and the provenance of its objects. Together they organise exhibitions addressing many of the complex issues of world history, and the many ways objects were acquired and have entered the collection; they also encourage curators in other countries to present their narratives of the objects from the British Museum. They welcome museum colleagues and heritage specialists from across the globe for training and skill sharing that enables all sides to learn from each other; they partner with institutions on all continents to build up cultural infrastructure; preserve cultural heritage; assist in the return of stolen or illicitly exported objects; and enhance experience and expertise, building up a global network of professionals.

The Museum is one of the most significant lenders of objects across the world and keeps circulating them through exhibitions and long-term loans. It has built up a comprehensive, publicly accessible database of the objects in the collection, and has accelerated the use of digital technologies to enable and facilitate exploration of the collection from anywhere in the world. Its inventories and archives are freely accessible, inviting independent research on the objects, the collections, and the history of the institution.[10] With continued investment in digitisation, information will progressively become available online to those who cannot physically visit the Museum and its archives.

There are myriads of ways of working together, using the collections, researching their history and provenance, or to open up a new understanding of a region’s culture. Exhibitions are among those tools. One example of how this can be done was India and the world, presented in 2017/18 at the CSMVS Museum in Mumbai and the National Museum in Delhi. Preceded by ten years of collaboration, training, smaller shows and research projects, this major exhibition was developed by a team of curators and scholars from Mumbai, Delhi and London to showcase 5500 years of Indian history in a global context, with all works pertaining to South Asia coming from Indian collections, and all works highlighting the global connections of South Asia coming from the British Museum. The show attracted far over 200,000 visitors in Mumbai alone, and involved hundreds of schools who seized the opportunity to have their pupils engage with a much wider perspective on Indian and global history than their institutions would normally offer, stressing among other aspects the grand multicultural, multi-faith traditions of India. It also offered digital introductions and presentations for those who could not attend or desired to deepen their experience following their visit. The exhibition has created a template, both as a method of collaboration and as a means to show the interconnectedness of a country and its various cultures.[11]

6. Object Journeys

The paths which objects have taken through time and space before entering the collection of the British Museum are numerous. The following paragraphs give an impression of just how varied these journeys have been and hint at the many complex stories of these objects. The final example, though not of one specific object, demonstrates the additional dimensions digital innovations offer for people from across the world to access the collection, engage with it and use it creatively.

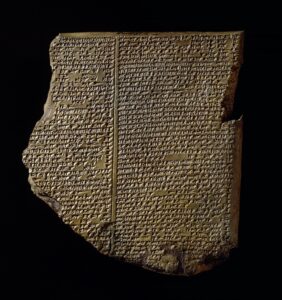

Stele of Ashurbanipal

Fig. 1, Stele of Ashurbanipal, 668-655 BCE, The Trustees of The British Museum.

This monument, dated to 668-655 BC was excavated in Babylon and has been part of the Museum’s collection since 1881. It shows Ashurbanipal, king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire that had been controlling formerly independent Babylon for centuries, lifting a large basket of earth for the ritual moulding of the first brick of the Temple of Marduk. The cuneiform inscription records Ashurbanipal’s restoration of a shrine in Babylon as example of his kingly might, the divine favour he was enjoying, and his many good acts as imperial overlord.

Under Ashurbanipal’s rule, from 669-631 BC, the Assyrian empire reached its maximum expansion through conquest and annexation, stretching from today’s Western Iran to the Eastern Mediterranean, from Turkey to the Persian Gulf and to Egypt. At its administrative and political centre, the royal city of Nineveh (present day Mosul, Iraq), a literary and visual court culture developed, based on the influx of riches from all over the empire, which produced highly sophisticated architecture and works of art, and the greatest library of the ancient world.

Assyria, however, soon fell victim to destruction by previously oppressed peoples, especially the Medes and Babylonians, and after 612 BC it sank into oblivion. Excavations by Paul-Emile Botta, and especially by Austen Henry Layard and Hormuzd Rassam from 1845-47 around Mosul, then part of the Ottoman Empire, brought to light the extraordinary reliefs that had adorned the walls of the royal palaces, extolling the prowess and success of the ruler (Fig. 2). On their second expedition from 1849-51, they uncovered the library of Ashurbanipal, which allowed cuneiform script to be deciphered by Henry Rawlinson, and which in turn opened up the entire literary heritage of ancient Mesopotamia (Fig. 3). Typically for those times, Rawlinson was a British East India Company army officer, a politician and a leading Orientalist, some calling him the Father of Assyriology.

Fig. 2, Relief caving, Assyian Soldiers demolish and loot the city of Hamanu. The Trustees of The British Museum.

With the permission of the Ottoman government, many of the finds were transferred to London and Paris, and triggered research into the ancient Middle East on an unprecedented scale, allowing for the rediscovery of the first states and empires in the region and their associated political, religious and administrative structures. After the fall of the Ottoman Empire, France and Great Britain carved up the Middle East along the lines of the Sykes-Picot agreement in order to secure access to the newly relevant natural resource oil. The creation of the Kingdom of Iraq under the Hashemite dynasty was one of the consequences of these developments, which has influenced the development of the region up to the present day.

British writer, political officer, administrator and archaeologist, Gertrude Bell, who played an important role in these developments, would also become instrumental in founding the National Library of Iraq, and in 1926 the Iraq Museum in Baghdad which quickly grew into a major institution to preserve and showcase Iraq’s cultural heritage, receiving the major finds from all over the country. Bell was also a key in introducing legislation on the protection of cultural heritage in Iraq in 1926-27.

Despite this promising start, a nearly unbroken series of conflicts driven by far-reaching power struggles, colonial demarcations, the scramble for raw materials and denominational and religious enmities has led to entire communities being attacked, killed or forced into exile. In the process, some of the most important historical sites, museums and objects, have been destroyed by war, subsequent looting and vandalism and, most recently by a short-lived radical regime, Daesh (the so-called ‘Islamic State’). In response to this systematic destruction of cultural heritage, some of the great museums and research institutes of the world, with the financial support of foundations and governments of numerous countries, have started, in collaboration with Iraqi colleagues, to help protect and preserve cultural heritage sites, monuments and museums in Iraq for present and future generations.

Fig. 3, The Flood Tablet, also known as The Gilgamesh Tablet from the Library of Ashurbanipal. The Trustees of the British Museum.

In 2015 the British Museum developed a scheme which, in the face of destruction, could offer something positive and constructive. The ‘Iraq Emergency Heritage Management Training Scheme’, or simply ‘Iraq Scheme’, which is supported by the UK government, builds capacity in the Iraq State Board of Antiquities and Heritage by training fifty of its staff in a wide variety of advanced techniques of retrieval and rescue archaeology. The programme, undertaken first in the UK and then on two specially selected archaeological sites in safe areas of Iraq, delivers state of the art training in all aspects of archaeological fieldwork, from geophysical and geomatic surveying and documentation, to complex excavation methodology. The training provides the participants with the expertise and skills they need to face the challenges of documenting and stabilising severely disrupted and damaged heritage sites in preparation for potential reconstruction. These two fieldwork projects are not ‘training excavations’ as such, but rather fully developed scientific excavations at which participants are offered instruction in the detailed techniques of field archaeology. Both excavation projects provide a wealth of experience for the participants.

Fig. 4, Installation of Lamassu by British Museum, Factum Arte and Iraqi colleagues at the University of Mosul, Mosul, Iraq.

On 24 October 2019, Factum Arte and the British Museum set up, in collaboration with colleagues in Iraq, high-resolution 3D copies of two Lamassu in the British Museum’s collection produced by Factum Arte (Lamassu are winged bulls, or as in this instance winged lions with crowned human heads, that flanked the entrances to Assyrian royal palaces). They were placed in front of the newly rebuilt Student Centre (Fig. 4), near the library building of Mosul University, one of the most important libraries of the Middle East that was destroyed by Islamic State. It is a statement about sharing, and about the importance of culture, at a time when digital can have an extraordinary impact in both the virtual and physical worlds. The event was celebrated by students and inhabitants of Mosul as an important step in the recovery of their cultural heritage.

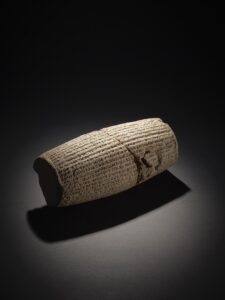

The Cyrus Cylinder

Fig. 5, The Cyrus Cylinder, The Trustees of The British Museum.

Territorial expansion, consolidation and assimilation of language, religion and culture have a long history as a political and social phenomenon. Numerous objects now in the British Museum show that the movement of people, ideas and things, both voluntarily and by force, has roots in deep human history and in the ancient world. The Cyrus Cylinder is one such example.

Named for its shape, the Cyrus Cylinder is an account written in the Babylonian language that documents the conquest of the great city of Babylon by Cyrus the Great, in 539 BC, which resulted in the assimilation of the Babylonian Empire into the growing Persian Empire. The cylinder was deposited in the city walls of Babylon around that date. Found at the site during a British Museum sponsored dig in 1879, it has been displayed more or less continually ever since.

The text, probably written on the orders of Cyrus, records the awfulness of Nabonidus, last King of Babylon, who is claimed to have perverted the cults of gods including Marduk, the presiding deity of Babylon. Marduk, we are told, selected Cyrus as his champion to restore the old ways and made him King of the World. Cyrus then marched on Babylon where the Babylonians welcomed him as their new king and delivered Nabonidus to him. Cyrus presents himself as a worshipper of Marduk who strives for peace, abolishes a labour service imposed on its free citizens, restores temples, religious cults, and previously deported gods and people. The cylinder also appears to support biblical evidence in the Book of Ezra, which tells us that Cyrus liberated the Jews and allowed them to return home. This has led to the assumption that Cyrus was a champion of humanitarian values, but although it is often described as a ‘first bill of human rights’, the surviving text on the cylinder contains no guarantee of human rights. In any case, such a concept would not have existed in Cyrus’ time. This is rather an official text justifying the annexation of Babylon by Persia and depicting an act of conquest as an act of salvation and restoration.

Adopted as an official emblem during the 2500th anniversary celebrations held by the last Shah for the founding of the Persian Empire, the cylinder was loaned to Iran in 1971 where it formed part of the festivities. Having acquired special reverence among Iranians, the cylinder was loaned again in 2010-11 to the National Museum in Tehran to figure in an exhibition curated by the museum’s staff. At a time of tense political relations this second loan of the cylinder was a moment of great significance both within Iran itself and for British-Iranian relations demonstrating how objects can act as agents of cultural dialogue. Today copies of the cylinder are omnipresent across Iran speaking of the country’s grand history, beneficial impact, and the clemency of the ruler granting rights and allowing peoples to return to their ancient lands.

The Meroë Head

The Meroë Head. The Trustees of The British Museum.

Empires result in the movement of people, ideas and things. Through their diffusion, objects not only acquire new meanings, but their survival may sometimes even result from having been removed from their original context. The Meroë Head, which is an over-life-sized bronze portrait bust of the first Roman emperor, Augustus (27 BC-AD 14), is an example of this, and a rare survival of a bronze statue from antiquity. It is believed to have been part of a statue erected early in the reign of Augustus in a Roman garrison town in Egypt, newly annexed by the Roman empire. Intended to project the power and omnipotence of the emperor, it served such a purpose for only a short period. Within a couple of years, it had been torn down by an invading enemy, the neighbouring Kushite Kingdom to the south of Egypt. They raided the Roman garrisons and looted the statues, transporting them hundreds of miles south to the Kushite capital at Meroë in present-day Sudan.

Most of the statues were returned following negotiations between the Meroitic Queen Amanirenas and the Roman general Petronius. However, this bust remained at Meroë where it was buried under the threshold of a temple dedicated to Victory. It appears to have been deliberately placed so that the Meroites could trample over it. This act of humiliation ultimately ensured its survival. It was discovered in 1910 by archaeologists led by John Garstang, having spent most of its history below ground and, therefore, out of sight. We do not know the name of the local workers who found the statue that day (as is so often the case). Garstang’s project, on behalf of the Institute of Archaeology at the University of Liverpool, worked under the recently established (1905) Antiquities Ordinance, created by the British administrators of the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium of Sudan (1899-1956). While this banned illicit export of antiquities from Sudan, it did allow for a partage system. This ensured sponsoring institutions in the UK and beyond could receive a share of the finds; through this route, the Augustus head arrived at the British Museum. The phenomenon of partage sits alongside other methods of acquisitions of this time, including diplomatic gifts from governments, acquisition of older collections, and purchases by individuals subsequently donated to the Museum.

The Rosetta Stone

Fig. 7, The Rosetta Stone, The Trustees of The British Museum.

The Rosetta Stone, one of the most famous objects in the British Museum collection, is inscribed with three versions of a decree issued at Memphis in 196 BC on behalf of King Ptolemy V Epiphanes, roughly 140 years after Alexander of Macedon had conquered Egypt. The Greek dynasty of the Ptolemies was installed after his death and ruled the country until it was conquered and incorporated into the Roman Empire.

The top and middle texts are in Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic and demotic scripts, while the bottom is in Ancient Greek. It is believed to have originally been displayed within a temple, possibly at Sais, and was probably moved in late antiquity or during the Mameluk period (1250-1517) where it was eventually used as building material for the foundation of fort Qaitbey near the town of Rashid (Rosetta) in the Nile Delta.

The Stone was discovered by a French soldier during Napoleon’s attempt to conquer Egypt from the Ottoman Empire which aimed to weaken British access to India. Transferred to the Institut d’Egypte in Cairo, copies were made for French scholars to work on. With the defeat of Napoleon’s armies by Britain, the Treaty of Alexandria set the terms of capitulation in 1801. This included thirteen antiquities, which despite French protests, were deemed state property, not the holdings of individual French soldiers or scholars. King George III subsequently donated the Rosetta Stone and the other twelve objects to the British Museum in 1802, and it has been on public display at the British Museum almost continuously ever since.

The Museum pioneered new printing and reproduction techniques and distributed copies and casts in the UK, France, Germany and the US immediately after the Rosetta Stone entered the collection.[12] This helped with the decipherment of hieroglyphs, finally cracked by Jean-François Champollion in 1822. Three more fragmentary copies of the same decree were discovered later, and a number of similar Egyptian bilingual or trilingual inscriptions are known today. The Rosetta Stone, though no longer unique, was the essential key to our modern understanding of ancient Egyptian literature and civilisation. Today, the term Rosetta Stone is being used metaphorically to refer to the essential clue to a new field of knowledge.

The British Museum currently collaborates closely with Egyptian colleagues on research, skill-sharing and documentation projects. Fieldwork at Naukratis in the Nile Delta explores the cosmopolitan port city with its Greek sanctuaries and harbour facilities, while at Shutb near Southern Egypt, there is work with the local community to explore continuities with the past. The ‘Circulating Artefacts’ project tracks and researches the movement of pharaonic antiquities beyond Egypt, helping combat illicit trade. A major project funded by the EU brings together the British Museum with four other major European institutions to provide technical assistance towards the redevelopment of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

The costume of the Chief Mourner, Tahiti

Fig. 8, The costume of the Chief Mourner, Tahiti, 18th C. The Trustees of the British Museum.

Museums cannot ignore difficult colonial legacies; objects collected by European explorers often present complex narratives regarding conquest, trade and ownership. However, there is often agency on both sides, which the British Museum seeks to explore through the research, conservation and display of objects. One such example, from a time preceding the colonisation of Tahiti, a Chief Mourner’s costume, was one of the star objects in the recent Reimagining Captain Cook: Pacific Perspectives exhibition that familiarised visitors with the appraisal of Cook’s voyages and their aftermath by today’s descendants of the people that inhabited the regions he explored, some of which would ultimately be incorporated into the British Empire.

In traditional Tahitian society the death of an important chief or high ranking individual was followed by a period of mourning. It was a fraught and uncertain time, and to manage the transition of power to a new chief or leader, a series of ceremonies were held known as Heva Tupapa’u, or ‘mourning for the corpse’. The Chief Mourner’s costume was carefully designed and painstakingly constructed from beaten bark cloth and plaited coconut fibre decorated with feathers, coconut shells and hundreds of pearl shells which shimmer when it is worn. It would strike awe into those who encountered it, including the crew who arrived with James Cook’s first voyage to the Pacific in 1769. The voyage botanist, Joseph Banks, described seeing a man wearing a ‘dress so extraordinary that I question whether words can give a tolerable idea of it’.

Cook and Banks attempted to procure a costume, but they were rebuffed, having been unable to offer the Tahitians anything they would consider worth exchanging. Instead, they made drawings. Cook’s disappointment at not being able to acquire a costume stayed with him and when he returned to Tahiti on his second voyage in 1774, he arrived prepared. This time, he brought red feathers from small parrots and lorikeets he had obtained on the islands of Tonga, having learned how much Tahitians valued them. Of the exchange, Cook wrote that during a visit from ‘the Royal Family’, Tu’s father ‘made me a present of a complete Mourning dress, curiosities we most valued, in return I gave him whatever he desired and distributed red feathers to all the others’. Cook purchased a number of complete mourner’s costumes, perhaps as many as ten, which he brought back to Britain aboard the HMS Resolution.

Cook’s interest in the costumes and persistence in acquiring them was, it transpires, crucial to their preservation. Another consequence of the arrival of early Europeans such as missionaries and the introduction of firearms was the disruption of traditional ceremonies, and the Heva Tupapa’u was soon abandoned. Other existing mourner’s costumes did not survive on the islands, and some were traded out to Europeans in various circumstances. Today, six complete examples survive in various institutions around the world.

Close interaction between the Museum’s curatorial, conservation and science teams, working with Tahitian specialists in preparation for the 2018 exhibition, revealed much new information about the costume, including the source of its feathers, as well as the emergence of two garments rolled into it, which had been previously thought to be padding. These collaborative discoveries have deepened understanding of this object, its role in traditional Tahitian culture, and of European contact with the people of Tahiti in the eighteenth century.

Benin Bronzes

Fig. 9, Benin plaque depicting the Oba flanked by two assistants with Portuguese figures in the background. 16th-17th C. CE. The Trustees of the British Museum.

The Kingdom of Benin was one of the most important precolonial states of West Africa and is known around the world for its sophisticated bronzes, many of which display narratives from the early life of the kingdom. Known to the Portuguese from the 15th century, since the earliest European voyages to West Africa, the kingdom became a major trading partner with Europeans. At this moment of European ‘contact’ Benin was already an important political formation and major trading state, situated within a regional network which connected it to trans-Saharan trade routes supplying gold, ivory and other products to the North African Islamic world and beyond. Benin’s place within history is equally known for its conquest by British forces in the late 19th century, an expedition which led to the sacking and looting of its capital and the scattering of the majority of Benin’s iconic bronzes around the world.

Today, Benin and its bronzes are the focus of international debates regarding cultural property and restitution. It is against this background that the Benin Dialogue Group has developed, a partnership of Nigerian and European museums and heritage institutions focused on realising the vision of a world-class permanent display of Benin Kingdom objects in Benin City, composed both of bronzes and other objects currently in Nigeria, and of international loans. The new Benin Royal Museum planned to house these objects, to be built by the commissioned architect Sir David Adjaye, will probably be one of the most significant African museum statements of the coming decade.

In the course of visits to Benin City by British Museum staff in both 2018 and 2019, the architect and a range of people across the city communicated the desire for new ways of thinking and learning about Benin’s past, and archaeology is seen as a central means of undertaking this new exploration. The British Museum intends to partner on such projects working together with Nigerian colleagues to explore Benin’s early history and in so doing to engage in new dialogues concerning the African and global past.

The archaeology of West Africa promises to shed new light on the histories of its precolonial empires and states and their global links via trans-Saharan trade routes from the medieval period. As demonstrated through the recent Caravans of Gold exhibition in North America, archaeology not only has the potential to dramatically improve understanding of these lesser-known aspects of Africa’s history, but also to help bring these to life and communicate them to a wide range of audiences within Nigeria and across the world.

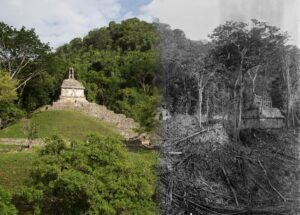

Exploring the Maya World[13]

Fig. 10, Exploring the Maya World Project, 2018-2019, Palenque then and now, incorporating an original photo by Alfred Maudslay from 1890-91. The Trustees of the British Museum.

A founding principle of the British Museum was, and remains that the collection and the information contained within it must be shared to the greatest possible extent. In collaboration with Google Arts and Culture, the British Museum has harnessed the power of new technology to capture and communicate stories of the collection, bringing them to a global audience through the Exploring the Maya World project.

Exploring the Maya World has digitised a remarkable collection testifying to the achievements of ancient Maya art and architecture gathered by Alfred Maudslay in the late 19th century. Maudslay used the latest technology of his time to capture and record the stories of ancient Maya cities in Mexico, Guatemala and Honduras: He created the first dry glass plate photographs of iconic sites like Palenque, Chichen Itza and Tikal, spending years living and working throughout the region. He also created more than 400 large plaster cast replicas of building facades and monuments, which have been stored in the British Museum for more than a century.

This collection represents some of the best-preserved records of ancient Maya writing. By working closely with colleagues in Mexico and Guatemala, the entire collection has been made available online for anyone to explore and research. The extraordinary stories that have emerged during this project have also been put online for people to enjoy in Spanish, Portuguese and English anywhere in the world.

The power of this project has been in its exceptionally collaborative approach: it has brought together curators, indigenous communities, scholars and technology specialists from across Mexico, Guatemala, the UK, Denmark, France and the US. Everyone has been united by a common mission to communicate the true value of conserving shared cultural heritage. Exploring the Maya World brings to life the energy and dynamism of culture in a way that can be hard to generate within a physical environment, and the voices in this project are vibrant and full of colour: they tell their own stories and the stories of those that have lived before.

The British Museum has the potential to reach many more people beyond those visiting the collection in London by bringing the Museum to the world virtually. Only a few years ago it would have seemed unrealistic to create a catalogue of 3D objects viewable from anywhere in the world, let alone walk around ancient Maya cities while sitting in your living room. These journeys of discovery are critical to engaging the most varied communities with the value of cultural heritage. Only by taking risks and by pushing the boundaries of what is possible can we begin to expand the reach and role of the 21st century global museum.

7. Future

How can we address the past to forge a better future? We can only do this together, through dialogue and collaboration, by constantly working to establish, in Jullien’s words, a ‘shared common ground of intelligibility’, with relentless disquiet and empathy. The collections of the British Museum come from many different cultural backgrounds, as do its visitors, seventy-five per cent originating from outside the UK. The Museum is committed to working with people from all communities to unlock the stories and meanings which resonate with them and their cultural concerns.

The Museum has embarked on a major campaign to renovate its building and to transform the presentation of the collection: the Rosetta Project. It will set a high priority on showcasing the interconnectedness of cultures in the future display in London. The Museum seeks to show the achievements of humankind and its many communities, and in order to do so it reaches out and invites different cultures to join the staff in planning the new Museum. In working with their representatives, the Museum will reflect their views and convictions and make other systems of knowledge and expertise accessible. Through its many partnerships across the globe, the Museum has created a strong basis on which to build. Together with colleagues and communities from across the world, the Museums’ curators have over the years developed relationships and established trust and openness, prerequisites to move on to ever more comprehensive, more sustainable and more equitable relations. The Museum has the responsibility and the desire to listen and learn, and to engage in difficult conversations in order to rewrite our shared, complicated history together.

Another important task is strengthening existing institutions and collaborating in building up new and additional infrastructure that allows people in all parts of the world to engage with cultural heritage, both their own and that of others. Together we can, and must, create a network of institutions that allows for the circulation of objects, and of the stories, ideas and debates they can trigger. The British Museum will be a passionate partner in making this happen.

One thing seems absolutely clear: the British Museum is a unique global resource for exploring the world in its ever-changing constellations, allowing the development of new perspectives on humanity’s shared pasts and investigating fresh responses to the shifting challenges of the present, as we find our way together, towards a better future.

[1] François Jullien, Il n’y a pas d’identité culturelle, (Paris: L’Herne, 2016)

[2] See Jonathan Williams, “Parliaments, Museums, Trustees, and the Provision of Public Benefit in the EighteenthCentury British Atlantic World”, Huntington Library Quarterly, 76, no. 2 (2013): 195214. The British Museum Act of 1753 was replaced by the British Museum Act of 1963 and enhanced by subsequent legislation, notably the Museums and Galleries Act 1992, the Human Tissue Act of 2004 regulating the return of human remains, and the Holocaust (Return of Cultural Objects) Act 2009 which do not change the basic legal structure of the institution.

[3] Chris Gosden, Archaeology and Colonialism, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 5.

[4] Ibid., 4.

[5] Ibid., 159. See also, Wellington Gahtan, M & Troelenberg, E (eds.), Collecting and Empires, (London: Harvey Miller Publishers, 2019).

[6] Felwine Sarr and Bénédicte Savoy, Rapport sur la restitution du patrimoine culturel africain, (Paris: Philippe Rey, 2018)

[7] These ideas are developed more comprehensively in Felwine Sarr, Afrotopia, (Paris: Philippe Rey, 2016).

[8] I am grateful to Sunil Khilnani for discussing these points in a recent conversation.

[9] Gosden, Archaeology and Colonialism, 259.

[10] See for instance Delbourgo’s critical appraisal of Hans Sloane, whose collection formed the basis of the British Museum. James Delbourgo, Collecting the World: Hans Sloane and the Origins of the British Museum, (London: Allen Lane, 2017)

[11] www.indiaandtheworld.org/

[12] A number of casts and copies were also presented to Egyptian institutions over the last 150 years.

[13] https://artsandculture.google.com/project/exploringthemayaworld.

Benin plaque depicting the Oba flanked by two assistants with Portuguese figures in the background. 16th-17th C. CE. The Trustees of the British Museum.

Benin plaque depicting the Oba flanked by two assistants with Portuguese figures in the background. 16th-17th C. CE. The Trustees of the British Museum.