A major change to the regulation of art businesses buried in a general bill modifying the Bank Secrecy Act passed in the U.S. House of Representatives on October 22 and is now pending in the Senate. A provision in the bill, HR 2514, Section 213, would add

‘persons trading or acting as an intermediary in the trade of antiquities, including an advisor, consultant or any other person who engages as a business in the solicitation of the sale of antiquities’

to the banking, casino, bullion and fine jewelry businesses already subject to FinCEN regulations. There has been no evidence presented that the U.S. antiquities trade is engaged in money laundering or of the involvement of any U.S. art dealer in the purchase of goods from ISIS – or any other actions financing terrorist activities. Nonetheless, claims that the art trade is ripe for abuse, and vulnerable to criminal exploitation, money laundering and terrorist financing form the arguments for proactively expanding FinCen rules to the antiquities trade.

Secret Service Asset Forfeiture and Money Laundering Task Force, photo by U.S. Secret Service, 10 October 2017. Public domain.

The Act is the “Coordinating Oversight, Upgrading and Innovating Technology, and Examiner Reform Act of 2019” or the “COUNTER Act of 2019”.

The Antiquities Coalition, an influential Washington organization, is urging that the bill cover all art businesses:

“Unless H.R. 2513 is further amended in the Senate to include art dealers, it will be a major missed opportunity, as antiquities are just one part of a much larger art market.”

FinCEN is the Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network. FinCEN regulations typically (for example in the case of jewelry or bullion traders) require reporting that discloses clients’ identities and personal financial information, requires dealers ascertain the source of clients’ funds, and ends client confidentiality, since FinCen shares the information in business’ files with law enforcement in the U.S. and 90 other nations, and with the IRS and tax authorities in 70 other nations. The bill does not contain the levels at which reporting must be made – but it applies to all transactions, not just cash. The threshold for required reporting will probably be similar to that in the jewelry and bullion trade. Reporting in these industries applies to virtually all businesses because there is a low $50,000 threshold in total transactions in regulated goods per year.

The bill was introduced by Congresswoman Carolyn Maloney (D-NY), whose constituency includes many galleries and small businesses that will be subject to the provision imposing financial regulation on antiques and antiquities trade. Passage of HR 2514’s Section 213 was urged by the Antiquities Coalition, a group that has repeatedly alleged that there is a multi-billion-dollar illicit art trade linked to terrorism and organized crime. U.S. law enforcement has not identified a single U.S. transaction in antiquities tied either to money-laundering or terrorism.

The Antiquities Coalition has ties to the government of Egypt and promotes national ownership of art. It argues against an art trade that it says deals in “blood antiquities.” It has promoted restrictive laws at conferences and venues along with representatives of the anti-money laundering (AML) compliance industry, which would gain a significant market for its services if the bill becomes law. Together, the groups have launched a Financial Crimes Task Force that the Antiquities Coalition describes as a “multi-stakeholder initiative aimed to protect the $26.6 billion U.S. art market from criminals and violent extremists.” The Antiquities Coalition and the Association of Certified Anti-Money Laundering Specialists (ACAMS) have argued the need for antiquities dealers to be subject to FinCEN regulations, apparently based upon a theoretical link between the estimated 3–5 percent of the global Gross Domestic Product said to be laundered funds, and the existence of a total global art market of $63.7 billion in 2017.

Art and antiquities businesses don’t believe they need this kind of “protection.” They already operate in a banking environment which require their transactions be recorded by financial institutions subject to FinCEN regulations making new laws both redundant and onerous. Section 213 of the bill was strongly opposed by industry groups including the art dealer international umbrella organization CINOA, the Art Dealers Association of America, the Authentic Tribal Art Dealers Association (ATADA), and organizations representing thousands of U.S. small businesses that sell collectible coins. Industry groups argued that the bill is a solution in search of a problem. No U.S. art dealer has been accused of any dealing in materials looted from the Middle East in the ISIS conflict and there is no evidence whatsoever of any connection between the art trade and terrorism. Industry representatives have noted the severe regulatory burden and high costs that will fall on the small businesses that make up almost all the antiquities and collectible coin trade. The regulations are likely to take days to fulfill and the estimated costs of compliance are estimated to be $5,000 or more each year, even for small businesses. Trade representatives pointed out that the trade currently utilizes banking methods and financial transfers already subject to strict FinCEN scrutiny.

Members of the House Financial Services Committee appear not to have considered art industry representatives’ evidence that the provision was not necessary. Arguments attempting to tie the art trade to ISIS are often long on moral outrage and noticeably short on facts. In addition, very few antiquities are either high value or liquid commodities, necessary prerequisites for money laundering activities.

Art businesses are extremely concerned that the bill’s vague scope and low thresholds for reporting requirements will expand FinCEN’s reach to businesses that will not be able to afford the costs of compliance. They are also concerned that the loss of privacy will deter ordinary art clients from buying.

The bill’s authors failed to include any definition of what ‘antiquities’ means in the text. ‘Antiquities’ is not a term defined under U.S. laws, and FinCEN regulators typically view their authority broadly. Because the term “antiquities” is undefined, it is possible that FinCEN will treat “antiquities” like “antiques” to capture information about sales of items 100 years old – currently 1919, next year 1920.

For example, the U.S. 1979 Archeological Resources Protection Act, does not use the term ‘antiquity’ but defines an ‘archaeological resource’ as anything human-made over 100 years old, regardless of whether it was found in the ground or merely an object in use of that age. The rolling date in the Archaeological Resource Protection Act means that today, an ‘archaeological resource’ can date to as late as 1919. (Some countries, including Russia, most of the former Eastern bloc, and many African nations define an ‘antiquity’ as any object over 50 years old.)

Antiquities businesses that are covered under the bill would have to establish an anti-money laundering (AML) program to:

- File IRS/FinCEN Form 8300, file FinCEN Form TD F 90-22.13, file FinCEN Form 105 to establish an AML program

- Appoint a Compliance Officer responsible for meeting FinCEN AML regulations and rules

- Provide ongoing AML training for employees

- Perform independent testing to monitor AML program and compliance

- File suspicious activity reports (SARS)

Thresholds in other regulated industries are as low as $2,000 for Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) – with only a $1,000 threshold for currency transactions. FinCEN also has the authority to change thresholds at any time. Even minor, technical reporting errors can lead to banks shutting down accounts, making it impossible to do business.

There are concerns that nations with aggressive repatriation policies and restrictive cultural patrimony laws (especially in the Middle East) could then use this information to demand the repatriation of art and artifacts traded in good faith for decades in the US and Europe.

There are typical characteristics of suspect transactions identified with possible money laundering. One characteristic of actual money laundering is that it is generally associated with criminal activity – and that participants in money laundering do so deliberately, knowing that wrongful activity is taking place. When legislation applies to an entire new class of businesses, that legislation is treating the business as if it avoids ordinary ways of doing business – taking checks and credit cards and using banks. This description does not fit the U.S. antiquities trade.

Money laundering implies knowledge by the people transacting business that there is a secret or hidden purpose for moving money or valuables. It usually involves complex transactions with large sums of money, sometimes in cash, or with substitutes for monetary instruments such as gems or bullion. Money laundering is found in transactions where there is no apparent lawful purpose or economic justification for the transaction, for example, when funds are exchanged for something of disproportionate value. The probability of money laundering taking place are increased when the parties to a transaction do not use ordinary banking facilities or live or work in countries identified as ‘high risk,’ for example, the ‘hawala’ system active throughout the Muslim world.[1]Again, this description does not fit the U.S. antiquities trade.

Art businesses and organizations have worked for years to educate themselves and the public about the signs and characteristics of money laundering activities. The Swiss-based international Responsible Art Market (RAM) group has already established widely-used guidelines for identifying and avoiding suspicious transactions. Many of the RAM guidelines have been adopted formally or informally by art trade organizations. ATADA, the Authentic Tribal Art Dealers Association, has established similar guidelines for its members in order to avoid potentially unlawful transactions involving Native American and other tribal art.

Instead of acknowledging that art businesses have come a long way in self-policing and regulation, the House of Representative’s passage of HR 2514, Section 213 perpetuates a dangerously misleading myth about terrorists funding their activities through the sale of art and antiquities. Not only did the Government Accounting Office (GAO) refute claims that antiquities were a significant source of ISIS funding, other studies such as the recent ILLICID report from Germany and the earlier report for the Dutch National Police have shown that despite the terrible destruction of monuments and sites in the Middle East, there has been no measurable increase in the amount of illicit trade, and no evidence of involvement of the antiquities business community in the trafficking of looted objects.

[1] Author Nikos Passas identifies a popular means of transfer of money through the hawala system as invoicing valueless objects as various commodities including ‘antiques’ being sent to India and other destinations, in ‘exchange’ for which worthless objects, cash is transferred to the West, in effect a reversal of what anti-trade activists claim is taking place. Informal Value Transfer Systems, Terrorism and Money Laundering, A Report to the National Institute of Justice. Northeastern University November 2003. Passas notes in that the vast majority of hawala transactions take place in completely legitimate transfers, in large part because the system is more reliable and trusted than government run financial systems. See Passas, Nikos (2006). “Demystifying Hawala: A Look into its Social Organization and Mechanics”. Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention. 7 (suppl 1): 46–62. doi:10.1080/14043850601029083.

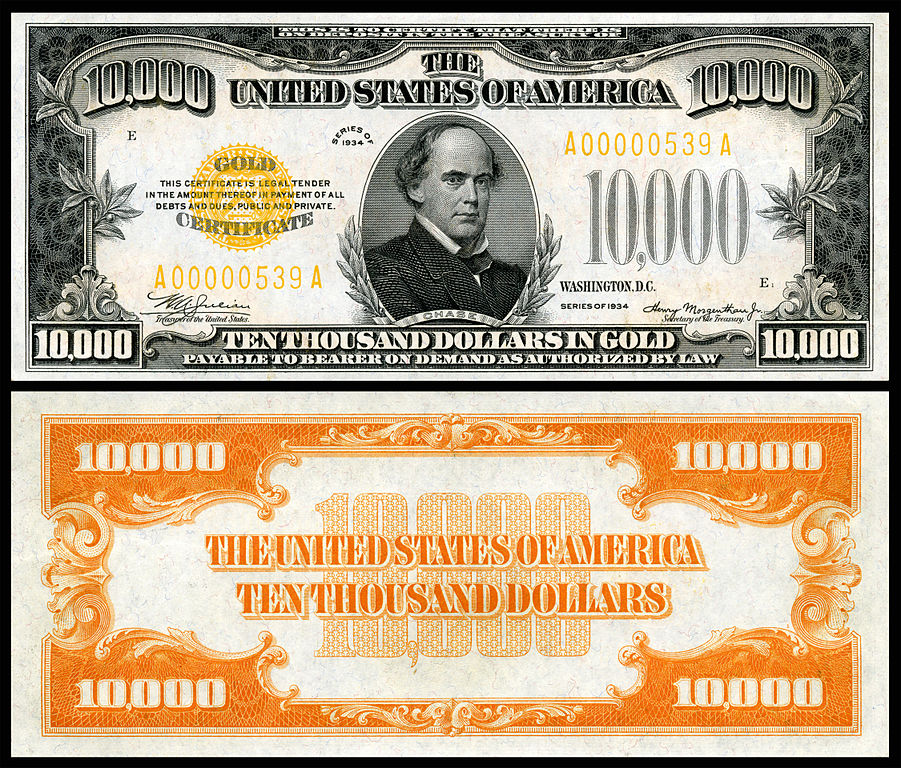

$10,000 Gold Certificate, Series 1934, depicting Salmon P. Chase, with signatures of W.A. Julian (Treasurer of the United States), and Henry Morgenthau, Jr. (Secretary of the Treasury). This series is illegal to own privately. From the Smithsonian Institution. Wikimedia Commons.

$10,000 Gold Certificate, Series 1934, depicting Salmon P. Chase, with signatures of W.A. Julian (Treasurer of the United States), and Henry Morgenthau, Jr. (Secretary of the Treasury). This series is illegal to own privately. From the Smithsonian Institution. Wikimedia Commons.