On June 7, 2019, the EU Regulation 2019/880, which severely limits the import of ancient art, books and manuscripts and antiques into the European Union, became law on its publication in the Official Journal of the European Union. The Regulation has been in the works since 2017. When fully implemented, it will likely act as a de facto ban on import of antiquities into the twenty-eight current EU nations – including the UK, if that country remains in the European Union.

Supporters of the European Parliament’s “Regulation on the introduction and import of cultural goods” have claimed that it is necessary in order to combat looting in unstable or war-torn countries, particularly in the Middle East. While halting trade of looted antiquities is a worthy goal, the Parliament and the Regulation’s proponents have not provided evidence for the claim that the art trade is encouraging looting of Middle Eastern artifacts; according to law enforcement sources in Britain, at least, the art trade has been vigilant in assisting authorities to locate looted goods.

The businesses likely to be hit hardest by the regulations are the legitimate traders, auction houses and small galleries dealing in art and collectibles in major art centers. These businesses are already subject to regulations on import and export transactions, banking, and tax collection under national laws. The U.S., E.U. and U.K. together dominate the $764 billion arts industry. Trade among these nations is very active and objects have traveled back and forth across the Atlantic for generations. The majority of the objects sold are long held and circulate from estates and private collections as well as from dealer inventory.

Scenes of Christ’s Passion, possibly by Georgios Klontzas (Greek, active 1603), Crete, Modern Greece, Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, USA. These and other images in this article are works legally owned by major museums in the US and UK, but similar objects in global circulation would have great difficulty meeting the criteria for documentation for EU entry under the new Regulation.

EU and UK market representatives have presented independently-verified evidence showing that key assumptions about supposed links to terrorism[1] and looting on which the proposed regulations are premised are wrong.[2] They believe that the cost and delay caused by the regulations would seriously damage the legitimate art and antique markets, which contributes about €17.5 billion to the EU economy, and provides employment for over 350,000 people. The burdensome Regulation will affect art fairs as much as brick-and-mortar businesses, as delays for obtaining import licenses for artworks would exclude most foreign dealers from participating in EU art fairs. A ‘compromise’ allowing objects short term entry for display in EU art fairs is of no help, since Customs officials must accept documentation and issue export licenses prior to release of the goods to buyers in the EU.

The main problem with the Regulation is that it fails to acknowledge or provide for the fact that very few artworks and antiquities have the kind of export documentation that the Regulation requires, since art source counties failed to provide it (while often tacitly allowing export even when forbidden by national law) and since proof of licit export was never previously required by customs for entry into the U.S. or E.U. The Regulation is not only likely to eliminate the majority of the export trade from the U.S. to the EU, it will lock most objects into the countries where they currently reside.

Fully Enforced By 2024-2026

In order to have equivalent import regulations in each EU nation, the Regulation requires all EU countries to adopt implementing acts within two years. EU officials have acknowledged that the Regulation could only be implemented through an online application system. For the new regulations to become fully operational, a unified electronic system for requesting import licenses must be in place. The regulations state that this must be complete within four years after passage of the first implementing acts. Therefore, the import licensing requirement is expected to be deferred until 2024 or even 2026 to enable harmonization of customs laws across the EU and for the development of the online system.

Challenging false assumptions, unworkable requirements and hasty decision-making

Rock Sample, Author: dun_deagh, National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh, Wikimedia Commons.

Regrettably, the majority of Parliamentary members have not only ignored the evidence submitted by the art trade, which is based on police and World Customs Organization data, but also failed to wait for the results of a study commissioned by Parliament itself before enacting final regulations. The EU Parliament commissioned a “Study on improving knowledge about illicit trade in cultural goods in the EU, and the new technologies available to combat it” in 2017, to be executed by Ecorys, but its delivery was delayed several times, and it has still not been delivered.

The recent election of a new batch of Members to the European Parliament offers some hope that they will take a fresh look at the false assumptions on which the Regulation was based, especially after the report commissioned by the Parliament on the illicit market is finally delivered. There is also some hope that the Regulation will be modified due to its unrealistic expectations for documentation, but it will require a major effort by the art trade to bring the facts to the new Parliament.

What Goods the Regulation 2019/880 Impacts

The Regulation restricts import and export of items over 250 years of age. For ancient art and “archaeological” materials, it requires either documentation of lawful export from the source country (although the majority of countries have no such permitting regimes) or if, in exceptional cases, the source country cannot be determined, the exporter must provide documentation from a second country in which the object has been for at least five years. For other categories of art, it requires a sworn affidavit from the exporter that the item meets the same criteria. A key concern regarding the affidavit system is that the importer may have no way to know if that is true or not, since cultural items may have circulated for decades among multiple owners.

‘Article 4’ Items Requiring Import Licenses

Boar hunting image from a krater, 550 BC, The British Museum, London, Wikimedia Commons.

- products of archaeological excavations (including regular and clandestine) or of archaeological discoveries on land or underwater

- elements of artistic or historical monuments or archaeological sites which have been dismembered

- Liturgical icons and statues

There is no value threshold for these cultural goods. All require proof of permitted export from the source country.

‘Article 4’ items listed in Part B of the Regulation’s Annex (other than objects originating in EU nation and being returned there, objects in museum exhibitions, or objects being granted ‘safe harbor’) require an import license. Article 4 states that issuance of a license requires “evidence that the cultural goods in question have been exported from the country where they were created or discovered in accordance with the laws and regulations of that country or providing evidence of the absence of such laws and regulations at the time they were taken out of its territory.”

There is an exception for cultural goods that have been in a third country for over five years if “the country where the cultural goods were created or discovered cannot be reliably determined” or if they were “taken out of the country where they were created or discovered before 24 April 1972.”

‘Article 5’ Items Requiring a Sworn Affidavit for Entry

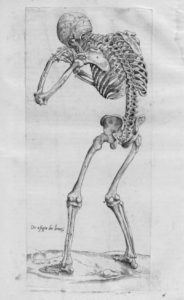

Anatomia Deudsch, Andreas Van Wesel (Author) (1514-1564), German, 1551, Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, USA.

Article 5 covers any of the following items which is over 200 years old and has a value of EUR 18,000 or more.

- rare collections and specimens of fauna, flora, minerals and anatomy, and objects of palaeontological interest

- property relating to history, including the history of science and technology and military and social history, to the life of national leaders, thinkers, scientists and artists and to events of national importance;

- antiquities, such as inscriptions, coins and engraved seals;

- objects of ethnological interest;

- objects of artistic interest, such as:

- pictures, paintings and drawings produced entirely by hand on any support and in any material (excluding industrial designs and manufactured articles decorated by hand);

- original engravings, prints and lithographs;

- original works of statuary art and sculpture in any material;

- original artistic assemblages and montages in any material;

- rare manuscripts and incunabula;

- old books, documents and publications of special interest (historical, artistic, scientific, literary, etc.) singly or in collections

These items are listed in Part C of the Annex. They will qualify for an import license if they are described in detail according to a standard such as Object ID, and are accompanied by a sworn statement from the importer that “the cultural goods have been exported from the country where they were created or discovered in accordance with the laws and regulations of that country at the time they were taken out of its territory.”

Requirements for entry of Article 5 cultural goods also include exceptions for goods that have been in a third country for over five years if “the country where the cultural goods were created or discovered cannot be reliably determined” or if they were “taken out of the country where they were created or discovered before 24 April 1972.”

Why the Art Trade Cannot Satisfy the Requirements for Import

Model of a River Boat, Meir, Egypt, ca. 2050 BC (Middle Kingdom), VO.1 (22.18, 22.19, 22.225) Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, USA.

In practical terms, the regulations could halt all imports of antiques and antiquities from countries that have a domestic law requiring “state permission” for export, but no history of ever issuing official export permits. Export permits have been extremely difficult, if not impossible, to obtain from almost every country that is a source for ancient and ethnographic art – including the nations of South and East Asia, Eastern Europe and the former Soviet bloc, Central Asia, South and Central America, Sub-Saharan and North Africa, and the Near East and the eastern Mediterranean.

Almost all art-source nations outside of the U.S. and Western Europe adopted laws in the late 20th or early 21st century nationalizing all art over 50-100 years of age and prohibiting its export. Few took actions to actually curb exports, and even fewer created export permitting systems except for temporary purposes such as restoration or museum loans.

Regardless of the date of export, very few artworks and antiquities still have paperwork showing the terms of export in sufficient detail to meet the standards under the EU Regulation.

To take the example of Egyptian antiquities, which are probably the most popular commodity in the antiquities market: Egypt licensed antiquities dealers and granted permits for export until 1983. The problem for importers will be showing proof of lawful export of these items. Even in the rare cases in which the original documentation has been retained for 50 years or more, Egyptian export permits generally did not describe individual objects, instead listing only the number of cases for tax purposes.[3] Under these circumstances, correlating an object to an export permit is virtually impossible.

Protests from Art, Antiques, Antiquities and Book Dealers

Medal of Henry IV of France (1553-1610), early 17th century (Baroque), French, bronze, Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, USA.

The IADAA (the International Association of Dealers in Ancient Art), CINOA (International Confederation of Art and Antique dealer associations) and ILAB (the International League of Antiquarian Booksellers) have all submitted protests against the Regulation. These organizations have worked tirelessly to inform Members of the EU Parliament over the last two years about the contributions of the art trade to stop the illegal trade and the adoption of due diligence practices to eliminate looted artifacts from the market. They have pointed out numerous times that the facts simply don’t support the EU Parliament’s assertions about the prevalence of money laundering and terrorist funding through art. They have explained how documentation going back to before 1972 simply does not exist for the vast majority of art objects in circulation. This information appears not to have penetrated the internal discussions of the Parliament. However, the IADAA deserve full credit for at least one sensible modification to the Regulation – reducing a proposed twenty-year stay requirement for objects in third countries to only five years.

Lack of Evidence For Terrorist Involvement or for Looted Art on the Market

The most challenging misapprehension among parliamentarians was an entrenched view that the Regulation was needed to thwart terrorist sales of ancient art. There is no evidence for any increase in European trade in artifacts from the Middle East. (See footnote 2 below, quoting Tim van Lit, B.Sc., Dutch National Police, Central Investigation Unit, War Crimes Unit report: Cultural Property, War Crimes and Islamic State, September 2016.) The World Customs Organization 2017 Illicit Trade Report, published in September 2018, also shows trafficking in cultural goods from the Mideast going almost exclusively to other Mideast destinations, not to Europe or the U.S.

In the U.S., there have so far been no takers for the $5 million dollar reward offered for information on looted art from the Middle East. According to James McAndrew, retired U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) agent, and former head of the DHS International Art and Antiquity Theft Investigations Program, “since the Arab Spring no looted archaeological item derived from ISIS was intercepted, seized, identified or discovered at any U.S. port of entry by any law enforcement agency.”[4]

Regulations Place Burden of Proof on the Importer

However, instead of requiring governments and Customs authorities to demonstrate that objects are illegal, the Regulation places the burden on the importer to show proof of lawful export from the country of origin by presenting permits for export from the source country. There is an exemption if a single possible country of origin cannot be determined, under which an importer can provide proof that an object has been lawfully exported from a third country where it has resided for at least five years.

When implemented, the regulation is likely to cripple European art markets

Book on Navigation, Piri Reis (Turkish, 1465-1555), Originally composed in 932 AH/AD 1525 and dedicated to Sultan Süleyman I (“The Magnificent”), this great work by Piri Reis (d. 962 AH/AD 1555) on navigation was later revised and expanded. Walters manuscript W.658, made mostly in the late 11th century AH/AD 17th, is based on the later expanded version and has some 240 exquisitely executed maps and portolan charts. Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, USA.

The practical consequences can only be estimated at this time, because the Regulation is still not clear about what documentation will suffice for importation and because some objects – coins and seals, for example – appear to fit into different categories, either as ‘archaeological’ or as ‘antique.’

Realistically, it seems clear that documentation requirements cannot be met by a majority of the antique and ancient objects in circulation today. In the case of antiquities, documented proof of either legal export from the source country or pre-1972 export will be required. This will prevent import of virtually all antiquities and many antiques. Under the regulations, a number of types of antiques over 200 years of age will require only a sworn affidavit attesting to legal export from the source country. However, since most antiques have passed from hand to hand for decades, a current owner may have no idea whether the original export was lawful, and have no basis for making a sworn affidavit.

New Digital System and Harmonization of Customs Regulations

Implementing the regulation will require multiple steps by the EU. Customs regulations for antiques and antiquities for each EU nation will need to be harmonized so the regulation is applied consistently throughout the EU. Officials have acknowledged that regulations could only be implemented through an online application system. Therefore the import licensing requirement is expected to be deferred until 2024 or at the latest, to June 28, 2025, to enable harmonization of customs laws across the EU and for the development of the online system.

Timing and process for obtaining import licenses.

On receipt of an application for an import license, the EU “competent authorities” must verify that all required documentation for import is complete, and request additional documentation within 21 days after receipt if needed. The authorities would then be required to issue or reject a license within 90 days of receipt of a complete application.

The “competent authority shall reject the application where it has information or reasonable grounds to believe that the goods were removed from the territory of the country where the cultural goods were created or discovered in breach of its laws and regulations… where the evidence required in paragraph 4 is not provided… where it has information or reasonable grounds to believe that the holder of the goods did not acquire them lawfully…[and] where the competent authority is informed that there are pending claims for return by the authorities of the country where the cultural goods were created or discovered.”

Orphan objects and similarities to the AAMD “1970 rule.”

The classes of objects subject to restriction from entry into the EU under the new agreement are similar to the objects subject to voluntary exclusion from acquisition and loans to U.S. museums under guidelines first set in 2008 by the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD), an organization composed of directors of major museums in the US, Canada, and Mexico. The AAMD guidelines for acquisition came to be known as the “1970 Rule” because they excluded consideration of objects for acquisition if they were imported into the U.S. after the 1970 UNESCO Convention, and did not have proof of lawful export from their source countries. As in the case of the EU Regulation, the AAMD instituted its policy without due consideration for the consequences. The result in the U.S. has been to create a body of objects, known as “orphan objects” which cannot find a home in museums because they lack documentation stretching back almost 50 years. The “orphan objects” are estimated to be in the hundreds of thousands.

The AAMD example raises the question of what will happen to the hundreds of thousands of objects currently in circulation between the U.S., U.K., and EU without documentation of an exportation date under the 2019 European Parliament “Regulation on the introduction and import of cultural goods,” if these objects can no longer circulate in the primary global art markets.

For more on the Regulatory Process and Effects of the Regulation See: Art Imports to EU Threatened by Draconian Regulation, Cultural Property News, December 29, 2018.

[1] The January 15, 2019, United Nations Security Council’s twenty-third report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team pursuant to resolutions 1526 (2004)and 2253 (2015), states: “82.Despite systematic consultation with Member States, the Monitoring Team has been unable to establish that ISIL ever generated significant funds from human slavery or sexual violence, although it was certainly massively engaged in such crimes on a basis internal to the so-called “caliphate”. Member States also broadly share the analysis that ISIL did not systematically or fully exploit the funding potential of looting and trading in antiquities and cultural goods. Nevertheless, it will not be possible to draw firm conclusions on this until more is known about what was taken, and until enhanced detection and enforcement efforts have yielded more information.” https://www.un.org/sc/ctc/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/N1846950_EN.pdf

[2] Tim van Lit, B.Sc., September 2016, Dutch National Police, Central Investigation Unit, War Crimes Unit reported in Cultural Property, War Crimes and Islamic State: “These claims are largely not supported by available government reports. (International and National) Customs Authorities have not reported growing influxes of illegal cultural property over their borders. Law enforcement agencies have not reported growing arrests of criminal art dealers or seizures of illegal cultural property from Syria and Iraq. Policy papers and studies do not present evidence that the illegal (online) art market flourishes and is overwhelmed with Syrian or Iraqi artefacts. Most museums have been evacuated and collections were hidden in secret storages, to prevent destruction and plunder. Media reports are rarely based on primary sources but rather copy each other’s headlines, leading to over exaggeration and unfounded estimates of IS revenues. Despite the lack of evidence for a large-scale illegal trade network benefiting IS, governments stress the importance of fighting this assumed vital source of income for IS.” http://iadaa.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Cultural-Property-War-crimes-and-Islamic-State-2016.pdf

[3] See Frederik Hagen and Kim Ryholt, The Antiquities Trade in Egypt 1880-1930, The H.O. Lange Papers, Scientia Danica. Series H, Humanistica, 4 · vol. 8, 2016. See also ‘Egypt demands Review of TEFEF Artworks; Study Shows Vast Majority of Egyptian Objects Around the World Acquired By Lawful Trade’, Cultural Property News, November 27, 2018, https://culturalpropertynews.org/ignoring-history-of-lawful-trade-egypt-demands-review-of-tefaf-artworks/

[4] James McAndrew, Speech at the Art Market and Money Laundering Symposium, presented by the Fashion Institute of Technology’s (FIT) Art Market Studies MA Program at the School of Graduate Studies & Case Western Reserve University’s School of Law (Oct. 12, 2018).

Hemicycle of the European Parliament in Strasbourg, July 2006, Author: JLogan, Wikimedia Commons.

Hemicycle of the European Parliament in Strasbourg, July 2006, Author: JLogan, Wikimedia Commons.