It’s a five-hour drive from Santa Fe into the tall mesas of the Arizona-New Mexico borderlands, but the scenery is spectacular and there is a warm welcome at the end of the journey. Since December of 2016, representatives of the Antique Tribal Art Dealers Association (ATADA) have been delivering sacred and ceremonial items back to tribal communities through an expanding program of private, voluntary returns.

The ATADA returns program was developed with the goal of building trust and facilitating communication between art dealers, collectors, and the tribes. The group hoped to encourage tribal members to be part of its community education programming, helping outsiders to understand the importance of preserving ceremonial items within the tribal community.

The meetings over the returns gave ATADA representatives the opportunity to explain directly to tribal leaders that the organization would work in partnership with them to support legislation that furthered tribal interests. This included legislation that would provide direct funding for cultural education, institution building, and for repatriating human remains or “ancestors” from overseas and from within US collections. ATADA representatives also made clear in meetings with tribal leaders that the organization could not support the 2016 STOP Act, or any other legislation that sought to expand NAGPRA into the private sphere. ATADA believes these measures would directly harm US businesses, museums, and collectors—and damage the arts economy that supports contemporary Native artists and their communities as well. Instead, ATADA would work to bring objects of importance directly back to the tribes.

The returns were sparked by a challenge from a Native American lawyer that former ATADA president Bob Gallegos met at a conference on repatriation in the fall of 2016. When Gallegos stated that he thought private individuals could do a better job than the federal government at bringing ceremonial items back to the tribes, she said, “Then, do it.” After consulting with the ATADA Board of Directors, who unanimously approved the project, he began to work.

Gallegos and other Board members gathered ceremonial items from willing donors, long-term collectors and art dealers, who felt that these objects – which are living entities for the tribes – should be in tribal hands. In one case, a Board member who knew of an important Zuni War God in a private collection, bought and then donated the item to facilitate the program. The donations made so far through the program have been ceremonial items that were collected prior to passage of NAGPRA in 1990. However, Gallegos says, “This program doesn’t focus on the legal issues; it’s about bringing back the key items needed by the tribes for the spiritual well-being of the community.”

The Hopi House, Grand Canyon Station, Grand Canyon, stereoscope image

When he had gathered the first group of ceremonial items, Gallegos reached out to old friends within the tribes. Some, who had been young carvers and artists when they had first met, were now respected elders. “I hadn’t seen some folks for thirty years or more,” he said, joking, “We’re all a little surprised at how well we’ve aged.” He explained that he wanted guidance on protocol. Contrary to the treatment of items by federal officials and law enforcement, he wanted to be sure that returns were undertaken with the utmost care in physical handling and respect for ritual and spiritual processes. Some tribes wanted photographs sent before delivery; in other situations, tribal leaders requested that there be no photographs, but drawings were made. The number of people who had contact with the returned items was kept to a minimum.

On the first visit to Hopi, the ATADA group met for several hours with tribal members who serve as Cultural Preservation officers and religious leaders. (Names have been withheld to protect their privacy.) The Hopi leaders explained the tribe’s concerns for retaining culturally important objects that are necessary to the well-being of their society. They raised issues of theft and misappropriation, assigning responsibility both to tribal members whose weaknesses had led them astray from the community responsibility they held for these sacred items and to outside buyers who exploited this. One spiritual leader was emphatic that it was part of his mission to correct present ills related to the past, and that he had a duty to find and return the katsinam (what collectors call masks, and the Hopi, “friends”) in order to ensure the future spiritual and societal health of the Hopi. He had been to Paris and met with a French collector there who was auctioning Hopi artifacts. Unable to convince him that giving them back was the right thing to do, he had invited the collector to Hopi. That experience was enough, and turned the collector around.

Before the ATADA group left, the leaders expressed their willingness to be part of a continuing educational program such as a seminar planned for May in Santa Fe. The ATADA group also shared what they knew of the history of the returned items. “They wanted to be sure that they had never been treated with pesticides, and would not harm anyone handling them,” said an ATADA member who accompanied the return. At last, the Hopi leaders took custody of the items, with due ceremony, and the meeting concluded with an embrace and a promise to return soon.

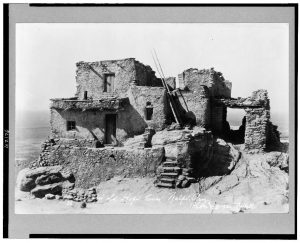

An old Hopi house, Walpi, Ariz. Photo c1920, Bostell, Library of Congress LC-USZ62-102176

Both spiritual leaders and members of the Zuni tribal government met the ATADA representatives at the border of the Zuni lands the next day. Unlike at Hopi, at Zuni, the physical transfer of the sacred items took place first—it was important that the Zuni take possession of the items before they could be properly transported within Zuni boundaries. The tribal members later explained that it would be harmful to the Zuni, to the visitors, and to the world in general if the sacred items were brought onto the land by outsiders. The returned war god and other items were received with prayers, and ATADA visitors then joined community members at the Zuni administrative center to discuss setting up protocols for additional returns, Zuni participation in planned seminars, and finally to share ATADA’s position on the then pending STOP Act legislation (which did not come to a vote in the Senate in 2016, but which is expected to be re-introduced in some form in 2017).

A Zuni councilman who is responsible for the oversight of all NAGPRA, NHPA, and the protection of sacred/cultural sites throughout the Southwest for the Pueblo of Zuni led the discussion. He and several others said that the Zuni supported the STOP Act, but acknowledged that there were legal and administrative issues with it. He indicated that the Zuni were already working on a written definition of tribal practice, a tribal law, that would prevent future instances of recognized sacred items leaving Zuni homelands. Passing such a law, effective on Zuni sovereign territory, also had the goal of giving the tribe greater standing in European courts. Gallegos and the other ATADA representatives agreed, noting that there were ancestral remains and sacred ritual objects abroad that could be the focus of future repatriations through establishing Zuni community ownership.

A Zuni spiritual leader also contributed a great deal to the discussion. He had interacted with the European press at the Paris auctions and met with collectors and French museum administrators. He described the difficulties he had faced attempting to convince Europeans, particularly European museums, to return human remains/ancestors and sacred objects. He said that despite the French institutions’ reluctance to return Zuni items, he had tried to help them by correcting attributions for Zuni objects and had identified objects that were not, in fact, Zuni-made.

He expressed gratitude for the voluntary returns, and said it was about time that the Zuni started a direct line of communication with private collectors. He pointed out that dealers and collectors needed to know that Zuni spiritual matters pertained to much more than the Zuni community; they were able to affect the world at large. Private collectors who unknowingly held Zuni items of religious importance could bring harm or illness on themselves or their neighbors without intending to do so. He too was willing to help by participating in future educational opportunities.

These first visits to Hopi and Zuni have been followed by others. Dozens of items have now been returned through the program, including a large group of items delivered to the Navajo Nation in March 2017, from a family that had held them for generations, and the grandchildren now wished to bring them back.

“And more to come,” says Gallegos. “The more people who hear about the program, the more have contacted me asking to make returns.” Gallegos says that he shares whatever he can with the tribal recipients, hoping that the information is useful for the tribe. It’s a privilege to be able to do this work, he says, as he starts the car for the five-hour drive home.

A full report on the ATADA Voluntary Returns Program will be presented at a symposium in May 22, 2017 in Santa Fe, NM.

Native American Heritage Event: Cultural Property Awareness: A Path to Healing Through Communication

The Antique Tribal Art Dealers Association and the School for Advanced Research will present a symposium, Cultural Property Awareness: A Path to Healing Through Communication, with a full day public presentation by tribal, academic, business, and legal specialists in cultural heritage on May 22, 2017 at the Eldorado Hotel, 309 W San Francisco St., Santa Fe, NM 97501. The event will be held in the Eldorado Ballroom, from 9am – 4:30pm.

The School for Advanced Research (SAR) is a research center located in Santa Fe, New Mexico. SAR supports advanced scholarship and creativity in the social sciences, the humanities, and Native American art. The Antique Tribal Art Dealers Association (ATADA) is a US nonprofit organization with both US and international art dealer, collector, and museum members. ATADA focuses on professional development and best practices for the trade in international and US tribal, ethnographic, and indigenous arts.

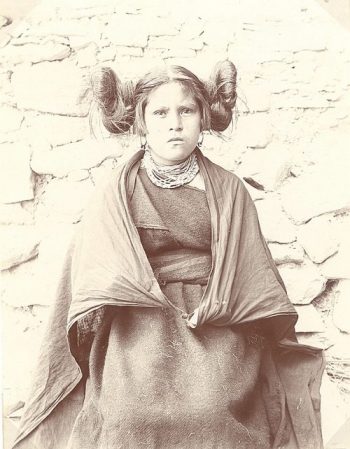

Young Hopi Woman

Young Hopi Woman