“Before meals, inmates chant, “Thank the Party! Thank the Motherland! Thank President Xi,” and sing revolutionary songs such as “Without the Communist Party, there is no New China.” …They must apologize repeatedly for wearing long clothes in Muslim style, praying, teaching the Qur’an to their children. Those who refuse to do so are punished with solitary confinement, beatings and food deprivation.”

Rachel Harris, “Securitisation and Mass Detentions in Xinjiang,” website of Harvard’s Central Eurasian Study Society.

“Although a certain number of people who have been indoctrinated with extremist ideology have not committed any crimes, they are already infected by the disease. There is always a risk that the illness will manifest itself at any moment, which would cause serious harm to the public. That is why they must be admitted to a re-education hospital in time to treat and cleanse the virus from their brain and restore their normal mind.”

Translation of an official Chinese Communist Party recording obtained by Radio Free Asia’s Uyghur Service.

“This is a mass incarceration targeting a specific ethnic group and a specific religion, which has similarities to the events that took place in Nazi Germany… The authorities say that they are in danger of being radicalized, and that this is an anti-terrorism measures, but I think that you can’t solve social problems with concentration camps.”

Poet Cui Haoxin, pen name An Ran, a member of China’s Hui ethnic group, as reported on Radio Free Asia on August 27, 2018.

A Million People in Internment Camps in Xinjiang

The government of the People’s Republic of China has imprisoned at least ten percent of the population in the far western province of Xinjiang, for no other crime than being Uyghur, Kazakh, or a member of another Muslim ethnicity. Muslim workers in other parts of China are being ordered to return to their hometowns, where many disappear.

Officials at a ribbon-cutting ceremony at the opening of a ‘re-education camp’ in the Xinjiang’s Korla city, in June 2018. Korla city website.

At least one million people, possibly more, have been incarcerated behind barbed-wire, in prisons with watchtowers, cells, and guards, and without access to family, attorneys, or any means of communication with the outside world. The Chinese call these “re-education” camps for “deradicalization.” Researchers report that the Chinese government is soliciting contractors for bids on building close to 100 more such ‘education centers,’ and job offers for ‘educators’ stress the value of police and military backgrounds; no teaching experience is required.

Many ethnic Uyghurs, Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, and members of other, smaller minority groups have been held for several years without charges or trials in these detention centers. The numbers of Uyghurs now being detained in these internment camps is unprecedented in recent history, even exceeding the number of Chinese sent to forced labor, ‘reeducation’ camps during the Cultural Revolution. China officially abolished its ‘re-education through labor’ system only in 2013.

Aggressive indoctrination, forced criticism of self and others, and torture, including beatings, hanging by the wrists for hours, being strapped for hours to a ‘tiger chair,’ and other abuses are common to the camps re-education programs.

The remaining Muslim population in Xinjiang is reeling from the shock. You can’t take that many people out of a society without affecting all – and there is literally no safe cultural space left to operate within. It is an ethnic cleansing to remove the ethnicity – the culture – from living human beings.

Academic Freedom Crushed

There have been many signs that China’s crackdown on Uyghur and other minority cultures was broadening. Although originally framed as a campaign to root out terrorists and Muslim extremists, China’s focus on eliminating expressions of traditional culture is nowhere more clear than in the ‘disappearance’ of eminent Uighur scholar and well-respected member of Chinese academe, Rahile Dawut.

Rahile Dawut, working in Xinjiang in 2005, Photo credit Lisa Ross.

Dawut is an internationally-respected ethnographer, folklorist, and researcher on Uyghur religious culture who founded a folklore institute at Xinjiang University. One day last December, she told colleagues that she was planning to leave immediately for Beijing from Urumqi in Xinjiang. Then she simply vanished. She never reached Beijing and has not been heard from in eight months.

Professor Dawut had previously been much praised by the Chinese government for her work. Her analysis of religious customs within Xinjiang should actually have given Chinese officials comfort; she had noted that religious beliefs among the Uyghur tended toward the moderate and familial. Many honored Sufi practices that groups like the Taliban and other Islamic extremists find abhorrent. Officials may have seen Dawut a threat simply because she was well-known internationally and had friends among her European and American colleagues. At least one of Dawut’s graduate students was picked up around the same time.

Dawut is just one of many well-known academic and cultural figures in Xinjiang who are believed to be in the camps. Rachel Harris of SOAS University of London listed other prominent individuals in Xinjiang who have disappeared into the camps: Xinjiang University officials including its President, Tashpolat Teyip, Professors Abduqadir Jalaleddin, and former Vice Provost of Xinjiang Medical Institute Halmurat Ghopur (now president of the Xinjiang Food and Drug Administration’s Department of Inspection and Supervision in Urumqi). Chinese officials often accuse Uyghur academics of being “two-faced” and insufficiently loyal to the state, or, like Ghopur, of having “nationalist tendencies.”

Dear Teacher (Söyümlük Muellim) video by Ablajan Awut Ayup (2016), Ablajan Ayub is among the ‘cultural’ figures to be interned, possibly for promoting Uyghur language education. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yPmdkB8Ww3Y

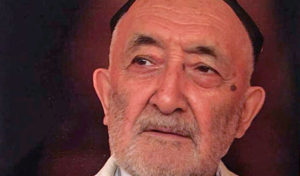

Cultural figures who have gone into the camps include pop star Ablajan Ayup, who is thought to have been detained for singing about Uyghur language education, football player Erfan Hezim, a pro-footballer detained for “visiting foreign countries,” and a deeply respected 82 year old religious scholar, Muhammad Salih Hajim, who “died in custody.”

Another important figure, Uyghur economist and writer Gilham Tohti, who founded Uyghur Online in 2006, suffered early on from China’s repression of free speech in Xinjiang. Despite his many assertions that, “My main agenda is to promote understanding between Uyghurs and Han Chinese,” he was harassed and prevented from traveling for years, then accused of “separatism” and finally, sentenced to life imprisonment in 2014.

Uyghur scholar Muhammad Salih Hajim, 82, who died in January 2018, about 40 days after he, his daughter and other relatives were detained, according to the Uyghur Human Rights Project (UHRP).

A recent article on the CESS blog strikes another fearful note for academics. Chagatay is an ancient Turkic language that remained in literary and scholarly use until the 19th century. Eric Schluessel writes that:

“The last time I was in Xinjiang, I learned that certain authorities were trying to repress training in Chaghatay and the use of Chaghatay sources for historical research. The excuse was that Chaghatay manuscripts, unlike printed Chinese books, were not “formal histories,” and thus could not be relied upon for finding “historical fact.” Moreover, I learned that many Uyghur students did not realize just how close Chaghatay is to their own modern language. Under the circumstances, reading more Chaghatay and giving more space to the voices of Chaghatay demonstrates that the international scholarly community values those voices. It produces, and may in the future institutionalize, practices and discourses that explore and valorize Chaghatay sources in anticipation of the day when scholarship is free again.”

Even subjects deemed relatively non-controversial in foreign academic settings, such as the economy, employment, and education, are often considered provocative and disloyal in China. This may be because while Xinjiang’s economy has grown enormously in recent decades, locals have not necessarily benefited by its expansion. Han Chinese immigrants to Xinjiang have captured most of the best-paying or official jobs. Guarantees under Chinese law that students will be able to study in native languages are undercut in Xinjiang as in Tibet: advanced public education is increasingly available only in Chinese.

Living in a World of Fear

The Chinese government claims that the detainees are dangerous extremists and that harsh measures are required to prevent violence from erupting in Xinjiang’s cities – key connecting points on China’s grand One Belt, One Road economic plan to dominate a huge section of the world’s economy. (See illustrated statement below.) As Adrian Zenz states in a recent article in Foreign Affairs, “The fact that a core region of President Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative is littered with internment camps is not a pretty picture to convey to the global community.”

Today, however, all of Xinjiang is a police state. There are cameras and a watchful police presence on every street in Xinjiang’s cities. Security is not only passively intrusive; there are barricades and police checkpoints everywhere that only Muslims must pass through, for checking IDs and doing facial recognition scans. Muslims who apply for passports must provide fingerprints, voiceprints, and DNA samples for analysis. Access to the non-Chinese Internet is virtually closed, and all Internet service cut for long periods. Wi-Fi sniffers gather data on any religious expression; police check cellphones for banned apps like Facebook. Big data is already promoted in China for social scoring; in Xinjiang it is currently an experimental model for social and political control.

Art depicting superiority of modernization versus religion, http://www.zonglanxinwen.com/img/fabbbc6bbacb.html

Bans on common daily behaviors are even more disruptive to the social fabric. People are now afraid to communicate even with friends and family – one never knows who is listening and reporting on you. There are bans on activities that had been ordinary parts of daily life – prayers, giving traditional greetings, and fasting on Ramadan are all considered anti-social markers demonstrating ones’ opposition to the Chinese government. You can be jailed for refusing to drink alcohol or eat pork. Talking or gathering in groups is forbidden. Children in school are encouraged to report on any ‘disloyal’ talk by their parents or elders.

The detention of parents and adult relatives has left some children in foster care and orphanages. Uyghur children in orphanages are credibly reported to be being fed pork and dog meat (favored by Chinese, but forbidden under Muslim practices). Uyghur children are also given new Chinese names and placed with Chinese families for foster care.

Apak Khoja Mosque, Kashgar. Wikimedia Commons

Social relationships are further undermined by the offering of cash rewards for reporting people wearing face coverings or beards, fasting during Ramadan, refusing to drink alcohol or possessing Korans. Even having a Muslim name is risky; Xinjiang newspapers are now full of legal announcements from worried parents who are changing their children’s’ names from traditional Muslim ones to Chinese.

Ethnic Muslims are living in a police state, but they have to go on living. The real ‘terror’ in Xinjiang is not Muslim extremism – it is what Uyghur and other religious and ethnic minorities feel every day, trying to live normal lives, not knowing what has happened to family members or friends, and wondering who will be taken away next.

Xinjiang

The Xinjiang region has been ruled by Turkic-speaking peoples, not Chinese, for centuries, a fact obscured or denied by many historians in China. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the region was known in the West as Eastern Turkestan. (Some locals used the name Altishahr, literally ”Six Cities”, a combined word with both Persian and Turkic elements) . The region was dominated by local rulers in the larger towns along major trade routes (such as in Khotan, Kashgar, Maralbashi, Aksu, Yengi Hissar, Yarkand, and Kucha).

8th century wall painting at Bezeklik, Tarim Basin.

There was a lengthy series of military contests between various Chinese and Muslim factions in the first half of the 20th century, but by 1949, China effectively became the central ruling power over the region. Despite repressive government policies, there has been relatively little overt resistance to Chinese occupation with the exception of serious riots in 2009, which were quickly and brutally quashed. Some degree of assimilation was seen by most Uyghurs as the only practical way to survive.

There have been movements, especially among the more educated Uyghurs, seeking greater autonomy within China since the 1990s. China’s violent repression of any movement toward independence has also resulted in a popular revival of Islamic culture and expressions of piety in the region. Discrimination has prompted awareness of difference, and for some Uyghurs, expressing this piety in minor ways became a conscious way of articulating their ethnic identity.

The reaction by the Chinese government has been overwhelming – a forced social engineering program designed to compel assimilation into Han culture and the erasure of a more than thousand-year-old Muslim identity in Chinese Central Asia. The camps embody this deliberate erasure of Uyghur identity. But the Chinese government, although it can no longer credibly deny their existence, refuses to publicly acknowledge what it is doing.

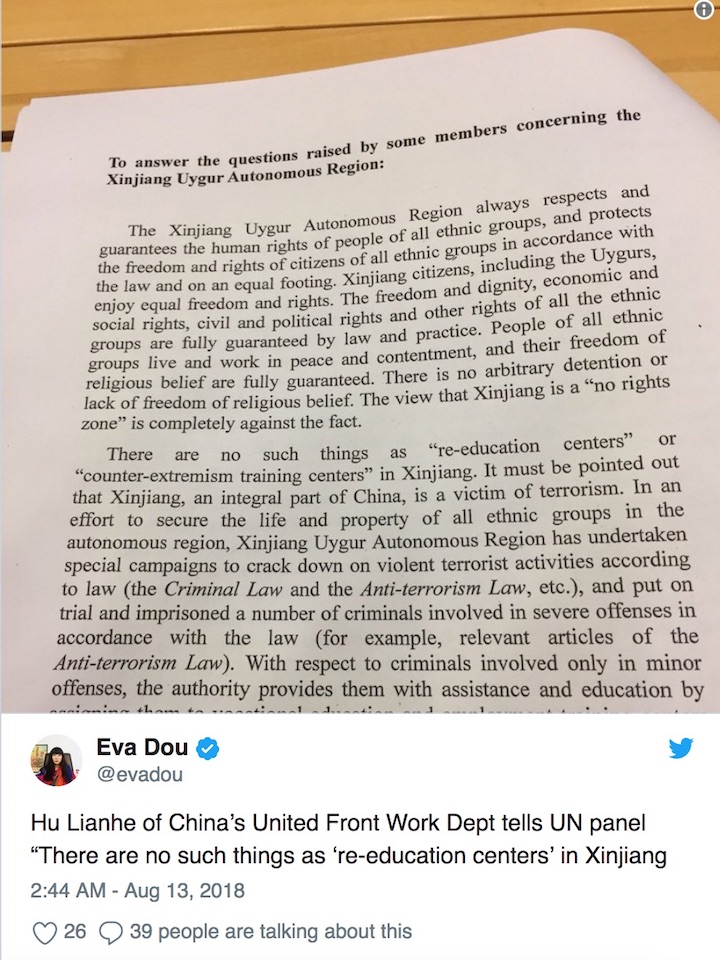

Chen Quanguo, who served as Secretary of the Communist Party in Tibet, was appointed to the same position in Xinjiang in 2016. His appointment is said to have increased repressive measures beyond anything before seen. Yet in February, Zhang Wei, China’s Consul General in Kazakhstan flatly denied the existence of the camps in an interview with a Kazakh newspaper. When a UN committee raised concerns over the camps in August 2018, the Chinese government continued to deny that people were interned or that harsh measures were being used against them.

The scale of detentions is so extraordinary that many in the West had refused to believe the initial reports of large scale internment camps in Xinjiang. Word has trickled out from a few who have returned from the camps, but only slowly. One reason, is that detention can be triggered simply by receiving a telephone call from a family member outside of China.

Now, however, people have been in detention for so long that families feel it is no longer possible to be quiet and hope to avoid further scrutiny. Western academics have seen their colleagues – prominent, even world-famous Uyghur academics and intellectuals – disappear, and fail to resurface – among the detainees who have been held for many months and even years.

PEN America and other academic freedom organizations have spoken out against the mass incarceration of Xinjiang’s people and China’s policy of silencing of academic, political, and social discourse. As PEN America’s Senior Director of Free Expression Programs, Summer Lopez, said in a PEN press release on August 10, 2018:

“The apparent months-long secret detention of Rahile Dawut is yet another illustration that Chinese governmental policy is geared towards erasing Uyghur identity. Like so many others, Dawut has apparently been targeted simply for being a voice for her culture.”

"Farmers" artwork showing common people attacking Islamic terrorists in the guise of rats. From an article by Darren Byler, "Imagining Re-engineered Muslims in Northwest China," at website The Art of Life in Chinese Central Asia.

"Farmers" artwork showing common people attacking Islamic terrorists in the guise of rats. From an article by Darren Byler, "Imagining Re-engineered Muslims in Northwest China," at website The Art of Life in Chinese Central Asia.