In May 2025, the World Monuments Fund revealed the discovery of over 100 previously undocumented archaeological structures at Gran Pajatén, a significant Chachapoya site nestled within Peru’s Río Abiseo National Park. The site straddles the La Libertad and San Martín regions between the Marañón and Huallaga rivers. Previously, Gran Pajatén was thought to consist of 26 circular stone buildings with slate mosaic decorations depicting human figures, birds, and geometric patterns, spread across terraces and stairways on a hilltop. The recent discoveries mark the most substantial archaeological find in the region since the 1980s, more than quadrupling the number of known structures at the site.

Gran Pajatén at Río Abiseo National Park. Photo by Heinz Plenge Pardo. Courtesy World Monuments Fund.

Although explorer Gene Savoy famously publicized Gran Pajatén’s “discovery” in 1965, local villagers from Pataz had already guided him there, and others may have encountered it even earlier. Gran Pajatén has since been recognized as both a UNESCO World Heritage Natural Site (1990) and Cultural Site (1992). Initial government clearing efforts in the 1960s inadvertently accelerated the deterioration of the stonework by removing protective vegetation. To safeguard the fragile ruins and surrounding ecosystem, public access has been strictly limited.

The Chachapoya civilization, often referred to as the “people of the cloud forest,” thrived between the 7th and 16th centuries in the northeastern Andes of Peru. Renowned for their distinctive circular stone buildings, intricate friezes, and cliffside burial sites, the Chachapoya developed complex societies in remote, mountainous terrains. Gran Pajatén, perched at approximately 2,850 meters above sea level, exemplifies their architectural prowess, featuring ceremonial structures adorned with slate mosaics depicting human and geometric motifs

The recent finds were facilitated by use of advanced non-invasive technologies, including aerial and terrestrial LiDAR scanning (topographic lidar typically uses a near-infrared laser to map the land), photogrammetry (measuring and interpreting multiple photographic images and patterns of electromagnetic radiant imagery), and technomorphological analysis (a research method used in archaeology that combines an examination of the technological aspects (how something was made) with a morphological analysis (its shape, structure, and form)). These methods allowed researchers to penetrate the dense cloud forest canopy, revealing a vast network of interconnected structures previously concealed by vegetation. The findings suggest that Gran Pajatén was not an isolated complex but part of an extensive network of pre-Hispanic settlements, indicating a more intricate societal organization than previously understood.

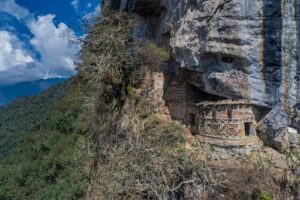

Los Pinchudos site during the 2022 expedition. Courtesy World Monuments Fund.

In conjunction with the discovery, World Monuments Fund undertook conservation efforts on one of the site’s most significant structures. The team conducted controlled vegetation clearing, detailed digital documentation, and structural stabilization, including the reinforcement of stairs and stone reliefs. A specially formulated clay-based mixture was used to replicate as much as possible the original construction materials.

Given the site’s ecological sensitivity and cultural importance, Gran Pajatén remains closed to general tourism. However, the World Monuments Fund plans to share the site’s rich history and recent discoveries through immersive digital storytelling, allowing broader public engagement without compromising the site’s integrity.

There are fascinating, related sites close to Gran Pajatén. Los Pinchudos is an elaborate Chachapoya funerary complex located in the same national park. The tombs—perched on a high rock cleft—feature brightly painted clay and stone structures with wooden roofs, adorned with anthropomorphic carvings (notably prominent phalluses, giving the site its nickname, los pinchudos is slang for “the ones with big penises”). This site has suffered damage from seismic activity and environmental exposure. Emergency stabilization efforts began at Los Pinchudos in 2000 with support from the World Monuments Fund. The area remains closed to all but scientific missions, in part to protect both the site and the endangered yellow-tailed woolly monkey that lives in the cloud forest.

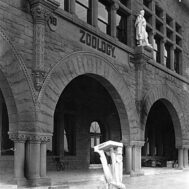

Kuelap,image of the fortress, April 2007, photo by José Porras, courtesy Elemaki, CCA-SA 2.5 Generic license.

Kuélap, another important Chachapoyas site, lies in the Amazonas region near the Utcubamba Valley, atop a limestone ridge at 3000 meters elevation. Built from the 6th century AD onward, Kuélap is a massive walled city with over 400 circular stone structures, monumental walls (10–20 meters high), decorative friezes, towers, ceremonial buildings, and a sophisticated water system. Rediscovered in 1843, Kuélap has been extensively studied and partially restored since the 20th century. However, the site has suffered structural damage, with a major wall collapse occurring in 2022.

Conservation has been funded by the World Monuments Fund (WMF) in Gran Pajatén since 2023. WMF also undertook emergency stabilization projects at Los Pinchudos in 2000 and 2002. Kuélap in Neither Gran Pajatén nor Los Pinchudos is open to tourism. Kuélap, which has been conserved by Peru’s Ministry of Culture, has been closed since the 2022 collapse. However, conservation and stabilization work is ongoing at all the sites. The Peruvian government has said that it is committed to reopening Kuélap eventually under stricter visitor controls. As in all such fragile mountain forest sites, balancing cultural tourism with site safety – both for visitors and for protection of the ruins themselves – is a central concern.

Staircase of Building 1 of Gran Pajatén, Peru. Photo by Heinz Plenge Pardo. Courtesy World Monuments Fund.

An exhibition at the Museo de Arte de Lima (MALI), running from May 21 to June 18, offers visitors an opportunity to explore the Chachapoya culture and delve into the details of WMF’s recent findings. The World Monuments Fund has also created a documentary, Abiseo, Cultural Forest of the Chachapoya on the discovery and restoration efforts.

World Monuments Fund team member in front of newly discovered building. Photo by Heinz Plenge Pardo. Courtesy World Monuments Fund.

World Monuments Fund team member in front of newly discovered building. Photo by Heinz Plenge Pardo. Courtesy World Monuments Fund.