The Origins of the Daguerreotypes and the Fight to Claim Them

In 1850, Harvard professor Louis Agassiz, the preeminent natural scientist of his day and founder of the science of glaciers – but also a proponent of the racist theory of polygenism – commissioned photographer Joseph T. Zealy to create a series of daguerreotypes depicting enslaved individuals.

Agassiz sought to use these images to provide visual “evidence” supporting his belief in the inherent inferiority of Black people. To that end, enslaved men and women, including a self-educated slave named Renty and his daughter Delia, were stripped to the waist, posed in dehumanizing positions, and photographed against their will. These daguerreotypes, among the earliest known images of enslaved African Americans, were not created to affirm their humanity but to reinforce the white supremacist ideology held by Agassiz and many others at that time.

Book on Harvard University, photographs of exterior of Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology and Agassiz Museum of Comparative Zoology, ca 1881-1886, CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

The photographs languished for decades in the archives of Harvard’s Peabody Museum, largely unknown to the public.

In 2017, Tamara Lanier, a Connecticut resident, discovered their existence while conducting genealogical research inspired by her mother’s dying wish to document their family history. Renty, she had been told since childhood, was their ancestor — a man who had taught himself and others to read in defiance of the law.

Through careful research and oral history, Lanier identified Renty and Delia in the Zealy daguerreotypes and began her efforts to have Harvard recognize her claim and return the images. Initially dismissed by the university and later denied by the courts on legal grounds, her campaign gradually gained national attention and evolved into a landmark legal and ethical dispute. The case raised important questions about whether historical artifacts, especially those connected to exploitation or violence, should be controlled by descendants of the victims or by scholarly institutions.

Although Lanier’s claims were initially rejected, a recent out-of-court settlement of a Lanier’s claims for emotional distress against Harvard University concerning the 1850 daguerreotypes of her enslaved ancestors marks a significant change in thinking about cultural heritage. Although no new legal precedent was set through litigation, and some of the settlement’s terms remain undisclosed, Harvard’s agreement to relinquish the images to the International African American Museum may signal a shift toward descendant-led stewardship for the legacy of American slavery.

Lanier v. President & Fellows of Harvard College, 191 N.E.3d 1063 (Mass. 2022)

The timeline of the case was as follows:

- 2017: Tamara Lanier contacts Harvard requesting return of daguerreotypes depicting her ancestors.

- 2019: Lanier sues for wrongful possession and expropriation.

- 2021: Massachusetts Superior Court dismisses the case on the basis of established property law—photographs belong to the photographer.

- 2022: Lanier appeals, and the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court revives Lanier’s claim, concluding that her emotional distress tort claim — but not her property-related claims — survived the motion to dismiss.

- 2023: Discovery phase approved; case progresses toward trial.

- 2025: Settlement reached; Harvard agrees to transfer daguerreotypes to the International African American Museum.

Property Law and the Control of Historical Artifacts

At the heart of Lanier v. Harvard lies a question of property law: Who owns the daguerreotypes of Renty and Delia? The Massachusetts Superior Court sided with Harvard, basing its ruling on settled legal doctrine.

Under both federal and state precedent, photographs are the intellectual and physical property of the photographer (here, Joseph T. Zealy), or their legal successor (Harvard). This rests on the principle that the photographer—not the subject—holds the copyright and physical rights to the image, unless a contract stipulates otherwise. No such contract existed with Renty or Delia, nor could it have, given the involuntary nature of the photographs. The court dismissed Lanier’s initial claims based on the following.

- Lack of standing: the court ruled that Tamara Lanier, while possibly a descendant of the photographed individuals, had no legal claim to the images as she was neither their legal representative nor did she have a recognized ownership interest.

- Statute of limitations: Even if Lanier had a plausible claim under civil rights or tort theories, the court found her case time-barred under the applicable statutes, particularly the Massachusetts Civil Rights Act’s three-year limitation.

However, Lanier and her attorneys presented additional legal claims:

- Equitable Restitution and Unjust Enrichment: Harvard has profited from the nonconsensual images—citing textbook covers and licensing. Harvard has benefited from the exploitation of images taken under conditions of extreme duress. However, without proof of ongoing profit or a contract breach, courts are reluctant to grant restitution in the absence of a fiduciary duty or direct loss to the plaintiff.

- Civil Rights and Constitutional Claims: The Massachusetts Civil Rights Act and a broader constitutional right to personhood were violated by Harvard by retaining and using these images. But courts require that the plaintiff show a direct and current deprivation of rights. The court found that these rights had expired for Renty and Delia and did not apply to Lanier herself.

- Prima Facie Tort: Prima facie tort allows suit for intentional infliction of harm without legal justification. Courts have typically rejected it when overlapping torts (like conversion or infliction of emotional distress) exist or when the alleged wrong arises from legal ownership, as in this case.

Interior, International African American Museum in Charleston, South Carolina, 2023, photo by Making it with the Matthews, CCA 3.0 Unported license.

Lanier’s other claims were grounded in the moral rights of descendants and personal injury to herself through infliction of emotional distress. The Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts found sufficient substance in these arguments and granted her application for direct appellate review.

Lanier’s arguments evoked the logic of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) and the Holocaust Expropriated Art Recovery Act (HEAR), both of which recognize intergenerational claims to cultural heritage. Lanier sought similar recognition for African American descendants of enslaved people—a population that remains legally unprotected by specific repatriation statutes.

Another claim was based on the infliction of trauma. Lanier claimed that the images were created to dehumanize. To allow Harvard to retain control was, in Lanier’s view, to continue a legacy of subjugation.

Arguments for Scholarly Stewardship

Harvard’s public interest argument contended that the images were vital historical records with significance beyond any one family. They are part of an archive of American racial history. Under current law, scholarship and public access may outweigh descendant claims when physical ownership is legally settled.

Likewise, Harvard argued that it was better equipped to preserve fragile artifacts and ensure wide public accessibility. Lanier, while not disputing the need for public access, argued that this can be achieved under descendant stewardship as well.

While the court acknowledged the ethical weight of Lanier’s claims, it suggested that redress is better suited to legislation or appellate courts.

The Settlement

In May 2025, Harvard agreed to surrender control of the daguerreotypes. Under the settlement agreement, not all of whose terms were disclosed, the images will not go to Lanier personally, but to the International African American Museum in Charleston, South Carolina. The agreement to pass the daguerreotypes to a museum focused on African-American history, located at a wharf where forty percent of the enslaved persons brought to the United States were disembarked, appears to balance institutional interests in preservation and scholarship with descendant claims to moral stewardship and interpretive control. The settlement also avoids setting a precedent establishing personal legal ownership by descendants that could invite further restitution claims under property law and erode scholarly interests in access to historical artifacts.

Stereoscopic photograph of the grave of Prof. Agassiz, Mount Auburn Cemetery, by unknown photographer, c. 1850-1920, from the Digital Commonwealth – 1 commonwealth sq87d5446

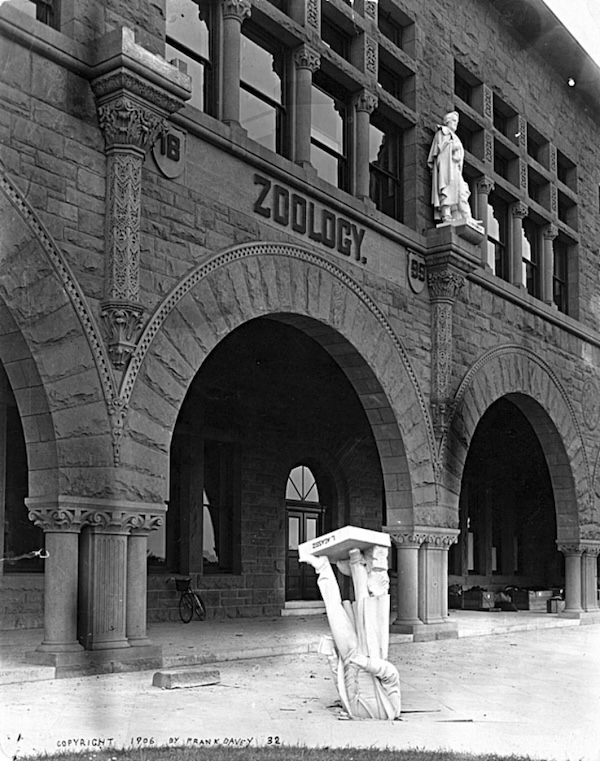

"Agassiz in the Concrete," Stanford University zoology building with fallen statue of zoologist Louis Agassiz implanted after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, 1906, photo Frank Davey (1860-1922), California Digital Library: The 1906 San Francisco Earthquake and Fire Digital Collection, public domain.

"Agassiz in the Concrete," Stanford University zoology building with fallen statue of zoologist Louis Agassiz implanted after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, 1906, photo Frank Davey (1860-1922), California Digital Library: The 1906 San Francisco Earthquake and Fire Digital Collection, public domain.