An incriminating case against Senior Curator Peter Higgs.

The research collection of one of the world’s greatest global art museums – a repository for hundreds of years of donated antiquities, from Victorian curiosities to exquisite archaeological ornaments – was the victim of an insider theft taking place over many years. According to a Complaint filed by the British Museum on March 26, 2024, it was no petty burglar but a renowned specialist in Greek and Roman art, Dr. Peter Higgs, who secretly removed and then tore precious intaglios and seals from their gold and silver mounts; a trusted, longtime employee who falsified records and attempted to mislead his academic colleagues to cover up his crimes. In ordinary business circumstances such insider crimes would be classified as employee embezzlement. Inside the British Museum, they became a scandal that rocked a great institution and all associated with it.

New details on the theft of more than 1800 objects from the British Museum’s ancient gems and jewelry storerooms have emerged from a civil law Complaint against the former senior curator at the museum. According to the Complaint, filed in the High Court of Justice, King’s Bench, Higgs’ senior status at the museum enabled him to purloin and sell hundreds of small ancient glass, gold and silver items that were not needed for display but stored in in the museum’s strongrooms. Higgs is accused of stripping ancient, semi-precious carved gems and glass cameos and intaglios of their mounts, then selling the gems for bargain-basement prices on eBay. The fate of the precious metal mounts isn’t explained in the museum’s initial Complaint, but they may have been sold for weight.

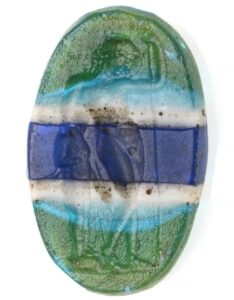

A glass gem with helmeted Athena, recovered by the British Museum, © Trustees of the British Museum.

The museum alleges that Higgs used his privileged access at the British Museum to alter or delete official written and computer records to disguise the thefts for years. Using false seller-names on eBay and PayPal accounts, Higgs appears to have sold objects from museum storerooms for a tiny fraction of their actual value. The thefts were primarily of unregistered pieces donated to the museum many decades before, examples of the ancient jewelry that was readily available to buyers, especially nineteenth and early twentieth century travelers in the Mediterranean. The popularity of ‘classical’ imagery and objects in this period led to extensive collecting of antiquities among the upper classes, for whom it was as de rigueur to have a Roman or Egyptian cabinet of curiosities as a collection of contemporary artworks is to a modern sophisticate today.

Literally thousands of such ancient trinkets – seals, cameos, rings, coins, medals, and other decorative items – were donated decades ago, when the British Museum was seen as the preeminent and most natural repository for all such items. These were some of the last objects to be left, unexhibited and unregistered, at the museum. Planning failures and an appalling lack of funding for documentation left the British Museums’ strongroom of ancient jewelry and other storerooms of items not on display vulnerable to thievery by an insider.

The losses of archaeological materials is particularly regrettable since over the last twenty-five years, the British Museum has managed – with considerable efficiency and skill – the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS), the best example in the world of an archaeological recovery and documentation system. The PAS records accidental and metal-detector archaeological finds by the public, ensures proper excavation, and has enabled study of more than 1.5 million digitally recorded archaeological finds since 1997. Would that the British Museum’s storerooms could have been treated as well as the thousands of found objects processed, photographed, and placed online by the PAS each year!

The theft has also revealed how vulnerable the museum is as a result of the current Trustees’ cost-cutting and failure to ensure basic maintenance and security. The British Museum’s leaky roof, which required staff, including its Director, to rush over to place buckets at night when it rained, is just one example.

Importantly, the scandal has also revealed that despite harboring one very bad apple, the museum has been blessed by a corps of extremely dedicated administrators and staff, who place the good of the museum and its collections above their own self-interest. They have to – since compared to other top museums, their salaries, from the director on down, are far lower than in the U.S. and other countries, and they are expected to work just as hard or harder. Clearly, the public and the press view the thefts as a wake-up call to the museum, but amidst the scandal over the losses there should also be an acknowledgement that the Trustees and the UK government have stinted the museum and it deserves far greater support from them.

A suspicious dealer uncovers the theft.

The thefts from the British Museum originally came to light through the persistence of an innocent buyer, Danish antiquities dealer Dr. Ittai Gradel. Commencing in 2014, Gradel began to acquire small yet valuable Greek, Roman, and Greco-Egyptian seals and jewelry at remarkably low prices on eBay. Among numerous other objects, Gradel purchased an agate Roman cameo for £15 and a Greco-Egyptian gold ring for £150 from a seller named ‘Sultan1966,’ who identified himself as “Paul Higgins.”

Plausibly enough, ‘Sultan1966’ claimed he had inherited these antiquities from his grandfather, who had operated a junk shop in York and passed away in 1953. However, in 2016, ‘Sultan1966’ posted a cameo fragment featuring a recognizable depiction of a girl, which piqued Gradel’s interest. Although the post was swiftly removed, Gradel saved the image and much later he was able to compare it to an apparently identical object on the British Museum’s website. Gradel also encountered a stone fragment portraying a man with a distinct hairstyle, previously offered by ‘Sultan1966’ but subsequently sold to another dealer, Malcolm Hay. Several years later, Gradel noticed a similar portrait from a 1926 British Museum catalog, raising his suspicions that the stone fragment had been stolen from the museum. Upon revisiting his payment records, Gradel discovered that the eBay account name ‘Paul Higgins’ was linked to a ‘Peter Higgs.’ Gradel shared this information with another dealer, who told the astonished Gradel that Peter Higgs was a senior curator at the British Museum, an unexpected suspect given his thirty years tenure at the museum and past contributions to identifying looted objects.

Several dealers attempted to alert the British Museum in 2020.

A yellow glass gem with a winged god, recovered by the British Museum, © Trustees of the British Museum.

Gradel sought the expertise of the Reverend Martin Henig, an archaeologist at Wolfson College, Oxford, in order to track down potentially stolen objects. Together, they identified a glass gem offered by ‘Sultan1966’ in a 1926 British Museum catalog. Gradel then informed Malcolm Hay, the current owner of the piece, that it originated from the museum. Although the museum was closed during the 2020 pandemic, Hay managed to meet with Deputy Director Jonathan Williams, who dismissed his concerns, saying the loss must have occurred during WWII. It now appears that Williams’ erroneous statement may have resulted from the insertion of a false handwritten note about the gem being lost in 1963 that had been inserted into the Museum’s records by Higgs. Williams is said to have accepted the stolen gem from Hay without further communication.

In 2020, Gradel stumbled upon a color image of the cameo fragment with the girl that he’d seen for sale before – this time on the British Museum’s public website, confirming its museum origin. In 2021, Gradel contacted Deputy Director Jonathan Williams, informing him of the cameo having been offered for sale, to which Williams responded that the gem was still in the museum. Again, Gradel felt he was being ignored.

After being brushed off again by Williams, Gradel contacted several British Museum trustees in late 2022. The dealer’s initial revelations spiraled into a serious scandal when a frustrated and alarmed Gradel finally went public in an interview with The Telegraph newspaper in August 2023, convinced that he had become an unknowing fencer of stolen objects. Within days, Higgs was fired for “gross misconduct” and Deputy Director Jonathan Williams was placed on leave (and later fired).

British Museum director Hartwig Fischer had relied on information from Williams that the case was regarding minor missing pieces and had been solved. Although he had known nothing of the potential scope of the thefts, Fischer took responsibility for museum’s errors, saying that it should have responded better, and resigned months before his planned departure in 2024. John Osborne, Chairman of the museum’s Board of Trustees ordered a detailed investigation. That investigation has provided the causes of action in the civil lawsuit filed against former curator Higgs by the museum, a summary of which follows. A criminal investigation by London’s Metropolitan Police Services (MPS) against Higgs is likewise in process, but he has not yet been formally charged. The MPS, PayPal UK and eBay UK are listed as third parties in the case, from whom information and access to data is sought by the museum.

The Complaint against Higgs.

Multicolored glass gem with a goddess, recovered by the British Museum, © Trustees of the British Museum.

During thirty years of employment at the museum, from 1993 to 2023, Higgs rose through museum ranks at the Department of Greece and Rome to hold the top position of Curator of Ancient Greek Collections. In the British Museum’s Complaint, Higgs is accused of conversion or trespass, breach of his employment contract and breach of fiduciary duty.

The Complaint alleges that Higgs’ abused his position of trust within the museum for at least ten years. It says that starting as early as 2009, Higgs stole over 1,800 glass and hardstone seals and cameos, earrings and other jewelry, and small gold and silver items, damaging many gems in the process by removing their gold or silver mounts. Higgs is said to have sold hundreds of items on eBay and other venues using a false identity and PayPal account. The museum’s Complaint says it can show that Higgs had access to the stolen items and that he sold at least some of them online using eBay and PayPal accounts which he now admits belonged to him.

The official procedure for accessing the Museum’s strongroom for ancient jewelry required two people to be present, but approved persons such as Dr. Higgs were allowed in without an escort. The museum kept records of the people who turned off the alarm or entered the strongroom where the missing objects were kept; these show at least 24 times when Higgs went into the strongroom between 2014 and 2023 and Higgs has accepted that he was sometimes alone there, browsing.

In its Complaint, the museum seeks access to data on Higgs’ computers so it can locate as many of the stolen items as possible before they are further transferred, or statutes of limitation expire. The Museum wants any stolen objects Higgs still possesses to be given back and to be given access to all relevant information on eleven electronic devices seized from Higgs home, now held by London’s Metropolitan Police Service.

The Museum’s complaint sets forth its accusations in considerably more detail than has previously been known. It was already alleged that Higgs attempted to cover his tracks in the initial thefts by using false names. The Complaint states that Higgs also tried to cover his tracks by falsifying museum records: creating false documents and deleting and manipulating records held on the Museum’s IT systems, deleting and breaking computer links between records, images and inventory. Two linked databases, MI+ records and Odin images, are the sources for the Museum’s public access website. The museum’s review of the edits made through Higgs’ computer account to the databases concluded that out of 98 edits he made to the databases, 83 related to items later discovered to be damaged or stolen. The Complaint gives the example of two edits to a description of a gem with an image of the Etruscan Herakles with a Cornucopia. After the edits, references to the mount were gone, leaving the impression that the item was a plain gem rather than a gem set into a gold ring.

Higgs was warned.

Among the fascinating details in the Summary Complaint reviewed by Cultural Property News is that Higgs may have been given a heads up that he was a suspect. The dealer who sparked the investigation, Ittai Gradel, has said it was his worst mistake to inform an archaeologist he knew of his suspicions. According to the Complaint,

“On Friday 26 February 2021, Dr Dorothy Lobel King, an independent archaeologist and writer, emailed the Defendant and told him that she thought someone was trying to “set him up” for selling cameos and intaglios from the Museum’s Collection on eBay. On Saturday 27 February 2021, the Defendant forwarded that email to Dr Jonathan Williams (then Deputy Director of the Museum)…”

Immediately afterward, Higgs created two misleading documents on March 1, 2021. The first was a report about the Hay gem, stating it had been lost many years before. The second was a list of unaccounted-for registered gems which he backdated and called “Gems not found by Documentation Team 2005,” placing this into the Museum records.

A rose glass gem with a profile head, recovered by the British Museum, © Trustees of the British Museum.

As well as attempting to cover his actions by inserting false records and sending Dr. King’s exculpating email to Williams, Higgs also appears to have immediately closed his eBay and PayPal account. Just one day after Higgs forwarded the King email to Williams, on February 28, 2021 the dealer, Dr. Gradel emailed the Museum claiming that Higgs had stolen and tried to sell three gems from the Museum, including the “Hay gem,” a “Socrates Gem” and an onyx cameo fragment, giving the Museum Higgs’ pseudonym of “Sultan1966.” The following day, Higgs created several false, backdated documents covering up the losses and inserted them into the Museum’s data systems.

For more than a year, the efforts by dealers to alert the museum to the thefts were dismissed by Deputy Director Williams, who seems to have discounted and minimized their claims in his reporting to Director Hartwig Fischer. Although the museum investigated the specific allegations made by Gradel, it is now clear that although one involved a glass gem still in the museum, a virtually identical gem made from the same mold had been stolen and that the cameo had been replaced in the collection, but its gold mount had been removed.

Finally, in 2022, the Museum appointed Dr. Aurelia Masson-Berghoff to conduct a full audit of the registered items in the Greek and Roman strongroom after three gold earrings that should have been in the strongroom could not be found in an annual audit procedure. Dr. Masson-Berghoff is an archaeologist and Egyptologist. Her diligent analysis – and insistence on reporting her findings despite pressure from Higgs have provided the factual finding showing how many objects were taken from the museum. It was no easy task. The Greek and Roman strongroom from which hundreds of items were removed contained both ‘registered’ items for which there was a paper record or which were listed in the museum’s MI+ database, and ‘unregistered ‘items which were unrecorded or for which there was another form of documentation located among other museum records.

According to the Complaint, Dr. Higgs tried to convince others at the museum to withhold information after he realized that the thefts were suspected. When questions about missing items in the storerooms were raised in late 2022, Higgs refused to report Dr. Masson-Berghoff’s findings, saying that staff shouldn’t be upset during the Christmas holiday. According to the Complaint, he tried to block the investigation by suggesting that he and Dr. Masson-Berghoff delete their texts and emails regarding the missing earrings (she refused his request, insisting that senior staff should be alerted), refusing to pass relevant information onto the Deputy Director of the Museum, and deleting information from his work laptops. By December 19th, Dr. Masson-Berghoff insisted on reporting her findings to senior staff members.

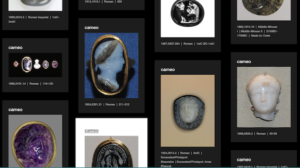

More of the over 3000 gems currently at the British Museum, © Trustees of the British Museum.

The museum then expanded Dr. Masson-Berghoff’s audit. An old, 1993 inventory of the strongroom showed that it held 1,449 unregistered items. 1,161 of these unregistered items were now missing – and this ‘unregistered’ category held in the Greek and Roman strongroom appears to be the source of the greatest number of missing objects. The museum’s Complaint alleges that there is evidence that another storage room, the Greek and Roman Life Reserve Room, where objects not on display were kept, was another source of stolen objects.

By comparing the results of a 2013-2016 reorganization and examining items that showed chips or scratches, inconsistency with prior weights and measures, and packaging that no longer fit the items’ original shapes, Dr. Masson-Berghoff concluded that:

“i) 188 registered items have been stolen; (ii) 237 registered items have been partially stolen (by the removal of gold mounts); and (iii) 73 registered items have been deliberately damaged (including by the apparent attempted removal of gold mounts).”

Another storeroom belonging to the Department of Britain, Europe and Pre-History appears to have been picked over as well; the precious metal mounts of 32 gems have been stolen or damaged.

Dr. Claudia Wagner has been investigating whether any of the items that Higgs listed for sale originated from the museum’s ‘unregistered’ collection. Her findings thus far indicate that a Socrates Gem, an intaglio depicting Eros hunting a crocodile, and a bronze ring featuring a glass intaglio of a Ptolemaic queen are all museum property. These items were among those sold by Higgs to Dr. Gradel.

The police seized a group of ancient bronze coins and medals from Higgs’ home, together with envelopes with handwritten notes. Comparing these envelopes with samples in the museum, the police infer that the items found in Higgs’ home also likely came from the Museum.

Financial transactions revealed.

Glass cameo in white and pink, recovered by the British Museum, © Trustees of the British Museum.

The MPS’ investigation into the sales made through Higg’s eBay account shows that 96 items resembling those in the museum’s collections were sold via eBay from May 23, 2014, to December 7, 2017, to around 45 buyers for small amounts. It should be noted that the dealers contacted by the museum have assisted greatly in the tracking and recovery of objects. Dr. Gradel alone has returned 350 items purchased from Higgs to the museum.

There is information on only selected sales in the museum’s summary – a fuller exposition will have to wait for when and if the museum’s or the criminal case goes to trial. The attempted sale of the Cameo Fragment to Ittai Gradel does serve as an example of how the investigation has been pieced together. On August 1, 2016, Higgs is known to have accessed the strongroom. On August 8, 2016, the cameo fragment with a girl was listed on eBay for £40 minimum, without its gold mount. (Undamaged, and with its mount, the cameo would have been valued at £30,000.) After he was offered £5,000, Higgs appeared to have been alarmed and retracted the listing. Higgs then altered the photograph of the cameo fragment in the database, apparently intending to remove it from the museum’s public database, but a system error left it in the database record. Higgs revisited the strongroom on August 9, 2016. Later, in correspondence with Gradel under his ‘Higgins’ pseudonym, Higgs claimed his sister wanted to keep it. The museum believes that Higgs realized that the gem’s uniqueness made it dangerous to sell, so he returned it to the strongroom, but it no longer had its mount.

The museum also says it established a connection between Higgs and antiquities sold to Rolf von Kiaer of Helios Gallery Antiquities, notably involving the gem, which Mr. Hay later returned to the Museum in the condition he received it, in a damaged state without its gold mount. Rolf von Kiaer had acquired the gem from Higgs’ phony eBay account in December 2015, along with numerous other antiquities that he purchased between July 2009 and November 2016. Some of these items were resold to buyers in the UK and abroad, including Dr. Gradel. One gem sold by Higgs to von Kiaer, then purchased by Gradel around February 2012, has been identified as a registered item from the British Museum’s collection. Additionally, von Kiaer purchased antiquities directly from “Paul Higgins” and “Simon Higgins,” both false names which Higgs used.

The complaint says that using another false name, Higgs sold 43 glass gems to a ‘Buyer J’ in the United States in 2017. The same Buyer J acquired or was offered over 300 additional gems via email, with the Defendant attributing their provenance to a bogus grandfather (though with a different story from the grandfather he described to Ittai Gradel).

About 15 years ago, a Mr. Szuhay acquired a 17th-century fragment of a cameo at Grays Antiques Market in Mayfair, which originated from the museum’s collection. Despite being unable to identify the seller, Mr. Szuhay has since returned the item to the Museum, which believes that it was likely stolen by Higgs.

Although 356 stolen items have so far been returned, contacting other buyers promptly increases the likelihood of further recovery. The Museum is keen to avoid any prejudice to the police’s criminal investigation but it fears that the longer it takes to locate the stolen items, the harder it will be to retrieve them. The Museum has agreed to follow a process of rolling disclosures with the police as its investigation moves forward.

Where the case goes from here.

British Museum, Great Court, Photo Paul Hudson from United Kingdom, 17 June 2013, CCA 2.0 Generic license.

Both eBay and PayPal have said they are willing to open Higgs’ records to the Museum. Metropolitan Police Services has agreed in principle to provide documents from Higgs’ devices “which are relevant to the recovery of Museum property” to an independent computer specialist – and Higgs has also agreed to allow this process.

The Museum’s filing notes that although Higgs disputes the allegations in its Complaint, he says he is “suffering from severe mental strain and is seeking counseling for mental health and depression and is unable to respond effectively to the proceedings.” Higgs hasn’t yet filed evidence in response to specific allegations. Except for what Higgs says is voluntary work by his solicitors in the criminal case, he was not represented in court in the civil matter.

Many of the sales of museum objects occurred years ago, posing challenges due to statutes of limitation for claims against recipients of stolen property. The Museum’s harm cannot be adequately compensated with monetary damages, as the value lies in the items themselves. Furthermore, even if the case against Higgs results in damages due to the museum, he will likely be unable to pay them.

The Order from the Court sought by the museum requiring Higgs to disclose information regarding the whereabouts of items from its collections would require Higgs to answer specific questions to the best of his ability. He can refuse to provide information covered by the privilege against self-incrimination but, it’s unlikely that privilege will apply, given that the potential charges against him fall under the Theft Act 1968, the Criminal Damage Act 1971, or the Fraud Act 2006, for which self-incrimination privilege is not available.

Some of the over 3000 exceptional gems, many with gold mounts, still safely under lock and key at the British Museum. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Some of the over 3000 exceptional gems, many with gold mounts, still safely under lock and key at the British Museum. © Trustees of the British Museum.