The Philosopher, bronze, Hellenistic Greek or Roman, circa 150 BCE to 200 CE, Cleveland Museum of Art.

An ancient bronze statue of man wearing a beautifully draped toga and sandals, headless, but still a figure of great power, is the focus of a rare challenge to the seizure powers of the New York County District Attorney. The statue, now known as the Philosopher, has rested at the Cleveland Museum of Art for 37 years and is valued today at approximately $20 million dollars. The statue remains at the museum, but it was “seized in place” by the New York DA under a warrant issued by a NY judge in August 2023.

The Cleveland Museum of Art has asked an Ohio court to declare that the museum is its rightful owner. The statue is one of the museum’s most important ancient artworks; ancient bronzes of this size and quality are very rare compared to statues made of marble, in part because the metal itself was valuable in ancient times and bronzes were often recycled into weaponry. The statue is considered either Hellenistic or Roman, with an estimated date of approximately 150 BCE to 200 CE, according to the museum’s latest research.

The case will be heard at the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Ohio, Eastern Division. The New York County District Attorney, also known as the Manhattan DA, announced that it was preparing legal papers in response.

It is a maxim that a museum is the best place to discover the truth about an object or to uncover a checkered history. The process can be simple – or take decades to unravel through scholarship. Museums are public, their collections are increasingly digitized, and over the last 20 years, museum standards of due diligence have moved dramatically toward thorough research of all objects prior to acquisition or even acceptance for donation. Provenance research and public transparency are now key elements of museum operations.

The Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA) is known for taking repatriation matters seriously. In past claims raised by art source countries for goods taken unlawfully from sites, the CMA has cooperated fully and engaged with the source country in investigating claims. The museum has taken pride in returning objects where source countries claims are warranted. The museum has also initiated its own returns when there was no claim, but its own research revealed that repatriation was merited. Among the valuable, cherished objects returned over past decades by the museum are a Cambodian statue of Hanuman beloved by the people of Cleveland and a famous marble head of Drusus Minor, son of the Roma Emperor Tiberius (see below). In 2008, the museum returned a group of 13 Italian antiquities based on newly available evidence from a case in Italy more than a decade before.

However, when the CMA believes it has right on its side, it’s not willing to be bullied by the NY DA. On October 19, 2023, the CMA filed suit against Alvin Bragg in his capacity as NY County District Attorney, arguing that the museum had good title to an object that has been one of its star exhibits for almost 40 years.

Debate over the origin of the statue

The main entrance of the 1916 wing of the Cleveland Museum of Art, photo by Zenbikescience, 23 April 2013, CCA 2.0 generic license.

The statue has been in the United States since long before the signing of the 1970 UNESCO Convention or passage of the U.S. legislation implementing the Convention in 1983. According to the museum, the statue was first exhibited at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston in the late 1960s. The statue was also exhibited from 1971-1974 at the Indianapolis Museum of Art, at the Minneapolis Institute of Art from 1976-1980, and then in 1981, at Rutgers University. It has been discussed in many scholarly articles in the U.S. and internationally, including in Turkey. Over the years, there has been speculation that the statue represented Sophocles, or another philosopher, or a noble in philosopher’s dress, or possibly the Emperor Lucius Veres or Marcus Aurelius. However, the identity of the person depicted is unknown and very unlikely ever to be known since it is headless.

The CMA purchased the statue for $1,850,000.00 in 1986 from Edward H. Merrin, Inc., a New York gallery founded in the 1960s. (Edward Merrin died in 2020; the gallery continues under the name Merrin Gallery.) The gallery warranted in its invoice that it was the lawful owner and held good title to the statue.

Researchers at the museum and elsewhere have studied the statue for years without finding clear indications of its origin. Its original attribution to the site of Bubon was not based upon evidence of its original findspot, but to link it with a known site where other bronze statues had been found. However, in 1987, within a year of its acquisition, the museum’s then Curator of Ancient Art, Arielle P. Kozloff, questioned the attribution to Bubon. Kozloff’s early research on the statue in Turkey appeared in an article in that year’s Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art, in which she suggested it did not originate but might have been moved there. (The first labels the museum placed on the piece indicated Bubon(?) with a question mark. Its more recent label is “Draped Male Figure, Roman or possibly Greek Hellenistic,” without a place of origin.) According to the museum’s Complaint, Kozloff’s later research has led her to conclude that there is no connection between the statue and the Bubon site.

Assistant DA Matthew Bogdanos uses criminal process to seize art from museums and collectors.

New York County Assistant DA Matthew Bogdanos, has virtually singlehandedly[1] made the return of antiquities to countries of origin one of the most prominent functions of the Manhattan District Attorney’s office. A count of press releases issued by the New York District Attorney shows that 7-10% of its press releases in recent years – covering all aspects of crime in Manhattan – have been about seizures or returns of allegedly “stolen” art to source countries by Bogdanos’ Antiquities Trafficking Unit. Virtually all of these seizures have to do with objects that have been in circulation in the art market or in museum collections for 30-80 years. Bogdanos is also largely responsible for promoting a widely held but inaccurate belief that antiquities trafficking is linked to trafficking in drugs and weapons, according to a study by the RAND Corporation.[2]

Assistant DA Matthew Bogdanos, former NY County DA Cyrus Vance and members of the antiquities trafficking unit with seized objects at a press event celebrating their achievements. Credit Office of New York District Attorney.

Bogdanos is by far the most active antiquities hunter in the United States. He and his staff of 28 investigators track down objects using foreign police data and images seized from traffickers from long-ago investigations that police still refuse to share with museums, auction houses or the public. (Christos Tsirogiannis, an investigator who worked very closely with Bogdanos has made headlines saying Bogdanos is claiming the credit for his work identifying objects from images that only he had access to.[3])

In the United States, anything “stolen” in the traditional sense of the word – taken unlawfully from a person or institution – will always be treated as stolen, and such items would be returned to their owners under both state and federal laws. However, an object considered “stolen” under a foreign national ownership law does not have to be “stolen” in the ordinary sense of the word.

Bogdanos’ definition of what is ‘stolen’ generally relies on foreign ‘national patrimony’ laws that state that all items of a certain age or type are state property. Foreign national patrimony laws often include unknown objects still under the ground, objects sold by their legal owners without permission of the government, and unregistered objects. Bogdanos argues that objects exported without permission after the passage of patrimony laws are “stolen” from the country of origin. Often, such foreign ownership laws are not compatible with U.S. concepts of private property rights, as the foreign laws essentially “nationalize” private property. Nonetheless, these foreign laws underpin the claim against the CMA’s statue and other claims made by the NY DA.

The CMA’s Complaint summarizes the criminal process followed in the New York County District Attorney’s “investigations of antiquities allegedly stolen from foreign nations” as follows:

“Unlike typical criminal investigations, the New York District Attorney’s primary purpose appears to be to return antiquities to their countries of origin or modem discovery, assuming the office can verify the appropriate country. In a January 2023 press release, the office stated that “the safe return of… lost pieces [is] the ultimate goal of all our investigators.” Although occasionally the District Attorney’s office has prosecuted people for the New York crimes of criminal possession of stolen property or conspiracy, far more often the office returns items to foreign countries without an announced corresponding criminal prosecution. Repatriation is typically accomplished in elaborate ceremonies open to the press and attended by the New York District Attorney and his staff, federal agents with the Department of Homeland Security, and diplomatic representatives from the countries at issue. News media in New York and elsewhere regularly cover the repatriation of “looted antiquities” by the District Attorney and his “Antiquities Trafficking Unit.”

“New York law allows the District Attorney to transfer these antiquities, previously seized by search warrant or turned over voluntarily, by obtaining an order from a New York judge with criminal jurisdiction sitting in New York State Supreme Court, Criminal Term, New York County. In most cases, the New York District Attorney persuades the possessor of the antiquity to stipulate that the possessor has no interest in the antiquity. That is not what happened in this case.”

Highlighting the NY DA’s application of criminal procedures to antiquities seizures from collectors and museums, the CMA’s Complaint notes that in the only two cases in which the possessor of the antiquity has contested the DA’s claims, New York’s criminal courts “have deferred to courts with civil jurisdiction to determine questions of title.”

The museum says there is insufficient evidence to support the DA’s “seizure in place”

Title is what is at issue in this case. Although it appears that the Manhattan DA is acting for Turkey’s benefit in seizing the statue, Turkey raised a claim with the museum 14 years ago, but appears to have abandoned it. According to the Complaint, the museum received a general request from Turkey’s Consul General for information on the statue and twenty other objects in 2009, but when the museum asked several times what information Turkey was seeking, there was no response, and there has been no response since, either in the form of a request for information or by Turkey filing a claim to the statue.

The CMA’s Complaint states that the NY DA’s claim is speculative and that there is no scientific or historical evidence sufficient to support the claim that the statue originated in Bubon, in Turkey.

How did the Cleveland Museum’s statue come under the control of the New York District Attorney?

The museum’s Complaint states that in informal discussions with the office of the NY District Attorney (and in the DA’s application for a search warrant issued in New York) the DA alleged that the bronze statue “is actually a statue of Marcus Aurelius, [and] was looted from the area formerly known as Bubon, and under Turkish patrimony law, must be turned over to the District Attorney for repatriation to Türkiye.”

Cleveland Museum of Art, photo by Erik Drost, 24 December 2021, CCA 2.0 Generic license.

In fact, the Complaint states that the DA’s office went so far as to obtain court orders allowing it to share evidence with the museum supporting its claim of a Bubon origin and to being a statue of Marcus Aurelius – evidence which the museum has told the DA is both “insufficient and inconsistent.” The museum states that its own research and that of outside experts “casts substantial doubt” on the identification of the statue as Marcus Aurelius or the allegation that the statue was ever in Bubon or even within the boundaries of Turkey.

The seizure of a statue in Cleveland by a District Attorney whose jurisdiction extends only to New York County could certainly raise jurisdictional concerns. The museum states that the DA required the museum to “agree not to contest a warrant from a state without jurisdiction in exchange for providing the museum with information” that might persuade it that the Philosopher statue came from Bubon.

When all the evidence was considered, the museum continued to find that it fell “short of persuasive proof.” When the museum suggested additional resources for the DA’s investigation to follow, their suggestions were declined.

The NY DA’s office gave notice to the museum on August 21 that it would seek a turnover order[4] in order to deliver the stolen property to the owner, “on satisfactory proof of his title.” The CMA is therefore seeking a declaration from the Ohio court, in a civil forum, that the museum is the lawful owner of the statue and has a right of possession superior to the N.Y. District Attorney. Such a declaration will be “satisfactory proof of title” and require the New York criminal court to release the object back to the museum.

The Cleveland Museum of Art has an exemplary record of repatriation when repatriation is merited.

Several advocates of repatriation have written about Cleveland’s questioning of the evidence for return of the Philosopher statue in harsh terms, as if any claim for repatriation by any country should be unresistingly followed, regardless of the evidence challenging that claim. But the CMA’s first duty is to the public it serves. The museum has a responsibility to conserve, research, protect and provide access to its collections in the public interest.

The Cleveland Museum of Art is a distinguished American ‘global museum.’ Its collections are highly regarded and it has a reputation for both connoisseurship and scholarly excellence.

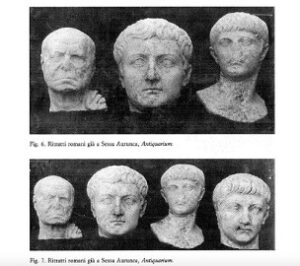

Portrait head of Drusus Minor, Cleveland Museum of Art.

The record shows that the Cleveland Museum of Art has willingly returned objects to source countries for which there was a legitimate claim. In 2017, for example, the CMA made the appropriate decision to voluntarily return a magnificent bust of Drusus Minor, the Emperor Tiberius’ adopted son, to Italy. At the time, Cultural Property News wrote that the museum should be praised for returning such a major object from its collection.

This earlier repatriation case shows just how convoluted and complex the tracing of an artwork’s history can be and how lengthy a journey an artwork make take before it comes to rest in a museum. The Cleveland Museum of Art worked in full cooperation with Italian scholars and authorities when previously unknown photographs apparently depicting the Drusus bust were unearthed from Italian records between 2011-2013. The photographs showed that the bust had been found in a 1926 excavation in Sessa Aurunca, in the province of Campania, Italy. The bust had been transferred to the Archaeological Museum Antiquarium di Sessa Aurunca, where it was stored.

The Drusus bust is now believed to have been stolen from the Sessa Aurunca museum in 1944 by occupying French troops and then likely taken by Algerian soldiers to North Africa. How it traveled from Algiers to France is not known for certainty. The bust was sold at a public auction in Paris in 2004, where it was illustrated in the catalog. It was purchased by the museum eight years later from Phoenix Ancient Art.

The Cleveland Museum of Art followed due diligence standards when it purchased the bust. It posted it on the Association of Art Museum Directors Art Registry, a public, online, database. It worked to fill in the gaps in provenance after the purchase, contacting prior owners and others. Michael Bennett, the CMA’s curator continued to research the artwork and raised additional questions about its origins.

1926 photograph of Drusus bust from Sessa Aurunuca excavations in Italy in 1926. Not published until 2011-2012.

As has happened in other cases of theft from archaeological inventory, Italian authorities had failed to make the 1944 theft public. The 1926 photograph of the Drusus portrait head was not published by Italy until some 90 years later. The connection between the Drusus head in the Cleveland Museum and the 1926 photograph was not made until Giuseppe Scarpati of the University of Naples published an article in 2014 suggesting that French occupation troops looted the bust from the museum, and that it was later taken by North African troops operating in the same locale.

The CMA’s Director, William M. Griswold, said that the museum was able to “establish to our satisfaction that the [Drusus] head is the same as the one in the [1926] photograph, and the head in the photograph was in all likelihood removed from the museum at Sessa Aurunca.” The marble bust was promptly removed from its gallery at the CMA and returned to Italy.

The controversy over who has rightful ownership of the Philosopher statue – the Cleveland Museum of Art or the N.Y. District Attorney’s office – is necessary and important to resolve. As the CMA’s Complaint states, the museum does not question “that the New York District Attorney sometimes gets it right and returns true stolen property to foreign nations. Based on the evidence adduced thus far and the opinions of experts available to the Museum, this is not one of those times.”

See also: Cultural Property News, Cleveland Museum Deserves Full Credit for Researching and Returning Head of Drusus to Italy, April 27, 2017, https://culturalpropertynews.org/cleveland-museum-deserves-full-credit-for-researching-and-returning-head-of-drusus-to-italy/

[1] Ariel Sabar, The Tomb Raiders of the Upper East Side, Inside the Manhattan DA’s Antiquities Trafficking Unit, The Atlantic, November 23, 2021, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2021/12/bogdanos-antiquities-new-york/620525/.

[2] Matthew Sargent, James V. Marrone, Alexandra Evans, Bilyana Lilly, Erik Nemeth, Stephen Dalzell, Tracking and Disrupting the Illicit Antiquities Trade with Open Source Data, The RAND Corporation, 2020 at 49-50. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2706.html.

[3] Dalya Alberge, ‘Enough is enough’: US looted treasures unit faces accusations over credit, The Guardian, September 26, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/science/2023/sep/26/antiquities-trafficking-unit-archaeologist-christos-tsirogiannis.

[4] The same type of order used in two earlier cases that contested the DA’s attempt to return objects to Italy and Iran, pursuant to N.Y. Penal Law § 450.10(5).

Cleveland Museum of Art, photo by Erik Drost, 7 November 2020, CCA 2.0 Generic license.

Cleveland Museum of Art, photo by Erik Drost, 7 November 2020, CCA 2.0 Generic license.