The ruins in Chaco Culture National Historical Park are some of the most culturally significant in the United States but are also notoriously difficult to access. The nearest airport is three and a half hours away. Over twenty miles of washboard dirt road separates visitors from the visitor center and the paved loop where one can see Pueblo Bonito, the 600 room multi-story great house that has inspired over 100 years of archeological excavation and research, not to mention multiple other great houses, kivas, petroglyphs and pictographs.

The Chaco campground is the only lodging in the park. The nearest motels are over 60 miles away. To make matters more challenging, the road into Chaco Canyon is composed of caliche clay which is slicker than ice when it gets wet. Since the area is so arid, this is primarily a problem during the heavy afternoon rains in July and August – which is also the height of the tourist season.

Chaco Great House at night, photo by K. Alden Peterson, US National Park Service.

Despite these obstacles, the National Park Service began planning a world-class museum exhibition space at Chaco Culture National Historic Park in 2010. By the end of 2016, Curator Wendy Bustard and the National Parks Service had collaborated with a dozen tribes and had arranged for loans of hundreds of Chacoan artifacts to be displayed in an exhibit at Chaco Canyon to open in the spring of 2017.

Many of these objects were from major museum collections, including the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, the National Museum of American History, and the National Museum of the American Indian, both in Washington, D.C. Artifacts that had rarely been displayed anywhere in the U.S. were to tell the story of Chaco culture in the place of their discovery.

It would have been a stunning experience to see a collection of Chaco artifacts within the context of the canyon. Unfortunately, despite repeated efforts to ensure that museum environmental standards would be met within the museum space, the climate control systems of the exhibit could not adjust to the local fluctuations of temperature and moisture. This failure would ultimately put artifacts at risk. The new superintendent of Chaco and Aztec Ruins, Michael Quijano-West, took one look at the climate control data at the end of 2016 and put the exhibition project on hold.

Cancelling plans to open the exhibition was an unexpected and serious disappointment to all of the communities and constituencies involved, from tribal organizations to archaeologists and to the lending institutions.

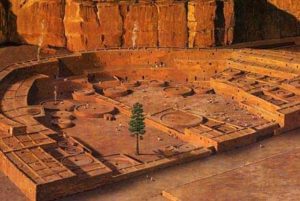

A digital model of ancient Pueblo Bonito, before it was abandoned. Source US National Aeronautics and Space Administration photo, Exploring the Sun Through Ancient Civilizations.

It is beyond dispute that a museum dedicated to Chaco culture should exist to teach the public about the riches of the Chaco Canyon-centered civilization that extended for hundreds of miles, and which had ties to other cultures throughout the Americas. The remnants of that civilization can still be traced in the culture of Native Americans living in the Four Corners region of the American Southwest. Chaco Culture is a significant piece of the cultural heritage of the United States.

If not in Chaco Canyon, then where should a museum to its culture be built?

Currently most of the artifacts from Chaco are stored and displayed in over 20 museums in the U.S. and around the world. The Chaco Culture National Park Service Museum Collection contains over 1 million Chaco artifacts that are stored and studied at the Hibben Center for Archaeological Research in Albuquerque, New Mexico at the University of New Mexico campus. The University’s Maxwell Museum of Anthropology also has artifacts from Chaco culture in its People of the Southwest permanent exhibition.

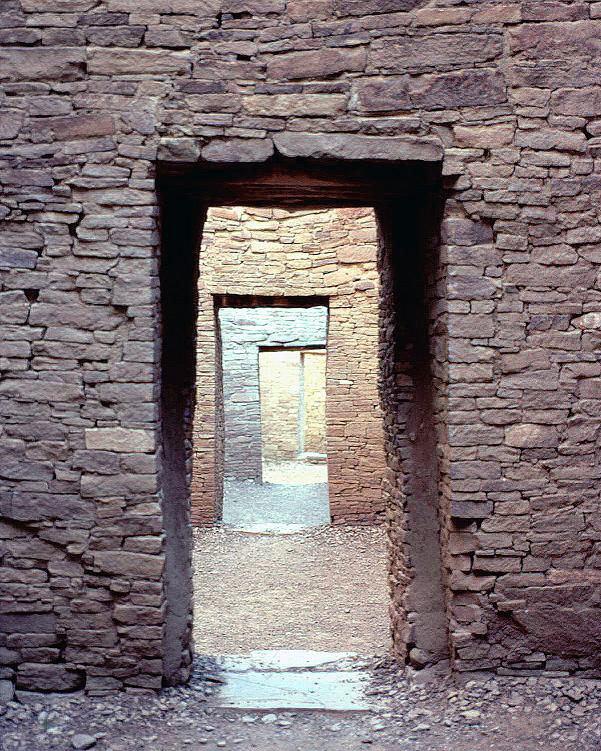

While a well-curated museum display can educate and inform, there is a special experience in viewing objects within the context where they were found. This is especially true in Chaco Canyon, as the alignment of the ancient buildings was integrated with the surrounding landscape and the movements of the sun and the moon. Seeing the objects that people used in their daily activity and ritual at Chaco in a nearby museum, and then walking through the doorways and into the rooms where these artifacts were used, would add a layer of understanding that can best be conveyed in proximity.

The road and its physical challenges are another problem – somewhat akin to the difficult decisions made recently to expand the number of lanes and build a lengthy tunnel to re-route a British highway immediately adjacent to the Stonehenge ruins.

Some proponents of greater access have proposed paving the road into Chaco Canyon; others have objected to this, citing the cost and possible disruption to ruins and sites in the vicinity. Most visitors feel that despite the challenges of accessing the canyon, the trip is will worth the effort and will be even more so when the museum is finished.

How long it will take to complete the museum is now in question. Superintendent Michael Quijano-West said, “It’s really up in the air right now.” Some sources say it may take up to five years more. Until the National Park Service optimizes the museum’s environmental controls, much of the collection can be viewed online at The Museum Collections of Chaco Culture Historic Park and at The Chaco Research Archive website.

Pueblo Bonito doorways, By National Park Service (United States), via Wikimedia Commons

Pueblo Bonito doorways, By National Park Service (United States), via Wikimedia Commons