Hun Sen and his wife pray at Angkor Wat ceremony, 2017, Voice of America screenshot.

On January 30, 2023, the Cultural Property Advisory Committee (CPAC) at the Department of State will hear testimony on the sixth proposed 5-year renewal of a Memorandum of Understanding (“MOU”) with Cambodia[1]. The Cultural Property Advisory Committee, an independent advisory body, must hold the State Department, the Cambodian Government, and the archaeological advocacy groups urging this renewal to the strict requirements of U.S. law: the Cultural Property Implementation Act (“CPIA”).[2] Any renewal of the MOU should be conditioned on trimming back the list of blocked items – now stretching from the Paleolithic to bead, textiles handicrafts of types sold in Cambodian, Thai and other tourist markets, and on holding Cambodia accountable for taking reasonable self-help actions as required under the law.

Actors portraying ancient royalty at Hun Sen’s 2017 Angkor Wat ceremony. No actual Cambodian royalty were invited.

Most importantly, any MOU should be based on the CPIA alone, not directed or influenced by diplomatic expediency or secret trade-offs of cultural interests for economic and military benefits – exposed by diplomatic cables revealed by WikiLeaks and set forth below.

Under the CPIA, import restrictions may only be applied to archaeological and ethnological artifacts of “cultural significance” “first discovered within” and “subject to the export control” of a specific UNESCO State Party.[3] They must be part of a “concerted international response” of other market nations, and can only be applied after less onerous “self-help” measures are tried.[4] They must also be consistent with the general interest of the international community in the interchange of cultural property among nations for scientific, cultural, and educational purposes.[5]

June 2013, opening ceremony of the 37th session of the World Heritage Committee in Cambodia with statued returned by Metropolitan Museum of Art. Prime Minister Hun Sen and Irina Bokova. Unesco.

The CPIA’s drafters knew a number of UNESCO State Parties were run by authoritarian governments that declared everything “old” State Property. For that reason, Congress structured the CPIA to ensure that the United States maintained its “independent judgment” as to whether and how the United States would enforce foreign nations’ export controls.[6]

Cambodia and “Stone Temple Nationalism”

It would be a serious error to consider ‘archaeological site protection’, the expansion of cultural knowledge, or even the development of museums and other specifically cultural goals in Cambodia as the key elements in the country’s heritage policies. On its surface, heritage actions by Cambodia’s government appear primarily driven by the financial rewards that international tourism brings to the elite. However, for Cambodia’s top politicians and military, cultural heritage is all about politics and serves far larger and more important goals.

Prime Minister Hun Sen greets a statue from Prasat Chen returned from the US. November 22, 2017.

In Cambodia, ‘heritage’ is about retaining political power and passing it on to chosen heirs, driving development, obtaining economic advantage, and maintaining a pathway to international acceptance despite the Cambodian regime’s appalling human rights abuses. As will be shown, heritage management in Cambodia is an enormously useful political tool. It operates within a complex web of economic and political relationships in which domestic politics and international economic tradeoffs dominate. Heritage rituals play a key part in perpetuating Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen’s[7] regime and his attempt to ensure the succession of his chosen heir, his son Hun Manet.[8]

Meanwhile, despite the enormous economic and diplomatic benefits conferred by ‘preservation’ projects at Angkor and other famous temple sites, much archaeology is neglected. Lesser-known sites go unprotected and government corruption still facilitates smuggling artworks to Thailand and Vietnam. While the U.S. media focuses on ‘stolen’ objects, little attention is paid to how many artworks in Western museums actually left the country under the auspices of French Indochinese authorities (including dozens ‘borrowed’ by French museums and never returned) or to government corruption that encouraged more recent looting.

Angkor, Cambodia, Preah Khan Temple, 27 November 2017, Photo Jakub Hałun, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

While nothing can excuse the rampant destruction and dismantling of temples in the second half of the 20th century, it is important to acknowledge that this was done in collusion with the Khmer Rouge and the military governments that followed. Today, the most extraordinary foreign collections of ancient Cambodian sculpture remain hidden in Thailand, not in France or other Western collections. Thailand’s top military and business establishments regard Khmer tradition as belonging to Thailand as much as Cambodia; the Thai perspective is that the objects smuggled from Cambodia to be erected in the mansions and spectacular gardens of oligarchs and generals is their heritage as well as Cambodia’s.

Despite its destructive history, a cynical ‘stone temple nationalism” flourishes in Cambodia. For the last thirty years and in Cambodia today, government leaders, especially its ’lifetime’ Prime Minister Hun Sen, have used cultural heritage ‘protection’ as a tool to secure primacy in domestic politics and to signal Cambodia’s commitment to participation in international affairs. Cultural claims and the ‘welcoming back’ of objects from Western museums and private collections are highly publicized; elaborate celebrations surround their return. Hun Sen demonstrates his religious devotion with public prayers. All such events ensure positive international press coverage for a regime otherwise known for extreme corruption and egregious human rights violations.

Hun Sen’s son Hun Manet at a diplomatic event in Japan, VOA photo. Drastic amendments to Cambodia’s Constitution “represent an attempt by Hun Sen to wrap his plans for dynastic succession – in which he will hand over power to his eldest son, Hun Manet – in constitutional protections, and constitutional legitimacy.” Benjamin Lawrence, ConstitutionNet, 2021

In Cambodia, “cultural heritage” also provides a veneer of domestic legitimacy by tying the present authoritarian government to the revered hero-rulers of the ancient past. As Voice of America noted in 2017, after opposition leader Kem Sokha had been jailed on what VOA described as “highly questionable treason charges”:

“Following the dissolution of Cambodia’s only credible opposition party, the country’s Prime Minister Hun Sen held a ceremony at Angkor Wat to pray for happiness and peace. Observers say Hun Sen is seeking to consolidate his legacy with divine symbology intended to elevate his status beyond mere politician…”

[At this event,] “5000 monks gathered before Angkor Wat to pray for peace. They were joined by actors, scouts, the national ballet, dignitaries, and politicians for a ceremony rich in regal symbolism. The extravaganza was also rich with political symbolism for Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen, who has just seen his main political rival, the Cambodian National Rescue Party, dissolved ahead of next year’s elections.”[9]

And as stated by Matthew Galway, in Praxis, in June 2022:

“There are two facets of Hun’s self-legitimation effort to establish and secure his own foundational dynasty. The first is his strategic invocation of an important legendary figure, Sdech Kan/Preah Srei Chettha II (ស្ដេចកន/ព្រះស្រីជេដ្ឋាទី២), a commoner who, in the early sixteenth century, usurped King Srey Sokonthor Bât, and thence came to embody the kingmaking myth of the nation. The second is Hun’s strategic use of royal symbolism to link himself to great rulers of the past and to connect his person to kingship even in the absence of royal lineage…”[10]

Chiseling out a frieze, Construction of a Monumental Temple to Hun Sen Victory in Phnom Penh, photo VOA, 2017.

Galway continues:

“A perfect example of this effort was on view during Hun Sen’s 2-3 December 2017 peace ceremony at Angkor Wat, which took place a mere two weeks after the CNRP had been dissolved. No members of the Cambodian royal family were present at the ceremony. The choice of location at Angkor Wat meant that this ceremony represented Hun Sen’s most brazen claim to the political lineage of ancient kingship. He also used this peace ceremony to wrest the title of “father of peace and reconciliation” away from Sihanouk. He thus drew upon “regal legitimations” to render his person inseparable from a heroic lineage of Khmer rulers and Cambodian peace and stability. His autocratic turn thus became justifiable in the name of royal continuity.”[11]

Embracing ‘ancient glory’ in politics in nothing new in Cambodia. While highly destructive of statuary of gods and temples throughout Cambodia, the Khmer Rouge made Angkor a key symbol of their utopian vision and celebrated their April 1975 victory with a three-day spectacle inside the Angkor Wat temple. Hun Sen’s 2017 event was an uncanny reminder of the Khmer Rouge’s celebrations almost 50 years before.

Angkor Wat

Since the 1980s, when the United Nations and UNESCO first engaged with a Cambodia emerging from the horrors of Khmer Rouge rule, Angkor Wat has been a potent international symbol. Its restoration symbolized Cambodia’s re-embrace of civilizing principles and reintegration into a world where humanitarian ideals and common responsibility for heritage counted.

Angkor, Cambodia, Preah Khan Temple, 27 November 2017, Photo Jakub Hałun, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

In fact, UNESCO facilitated the rehabilitation of the Khmer Rouge after they were driven into exile by Vietnamese forces. Recognized in their Paris exile as the leaders of “Democratic Kampuchea” by the UN, the Khmer Rouge argued that Angkor should become neutral territory in order to facilitate its protection.[12] In Vietnamese hands, they claimed, Angkor Wat was neglected and a trade in antiquities was booming. During the 1989 peace negotiations, Hun Sen, then head of the ‘Republic of Kampuchea’ inside Cambodia, also sought help from UNESCO at Angkor. In 1992, after UN-supervised elections, Angkor was inscribed on the World Heritage List and its international reconstruction and preservation effort became the gateway for international cooperation and development in a new Cambodia.

UNESCO originally supervised about 100 international projects there, making Angkor the largest archaeological site in the world. Since 1995, Cambodia’s national administrative partner, the Authority for the Protection and Management of Angkor and the Region of Siem Reap (APSARA) has acted as manager and coordinator of dozens more projects.

Foreign projects at Angkor in particular have enabled participating nations to infuse conservation projects with positive political meaning, even if there were serious problems with the programs themselves. The first French management plan was unsuccessful, and replaced by privatized administration, which became mired in corporate collusion.[13] Subsequent Japanese involvement was deemed more successful, though it served Japanese corporate interests as well as signaling Japan’s desire to amend relations in SE Asia.

However, Cambodia is beset with serious corruption that directly impacts its cultural heritage sector, particularly the Angkor Wat archaeological park, a cash cow for the Cambodian economy. In 1999, a local conglomerate named Sokimex with close ties to the ruling regime, received a contract to conduct ticket sales. After complaints about possible corruption, the government itself took over these sales directly in 2015.[14] Corruption concerns surrounding park revenue have persisted ever since.

Angkor Wat, tourists on the stairs, Photo Gerd Eichmann, 29 January 2007, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

In May 2020, the Cambodian government signed a fifty-year land lease deal with NagaCorp Ltd. one of the largest gaming entertainment companies in Southeast Asia. The lease included plans to build a non-gaming amusement park with integrated luxury hotels, a water-park and shopping and entertainment district just 500 meters from the protective zone surrounding Angkor, to be called “Angkor Lake of Wonder.”

It is hard to see how NagaCorp’s goal “to promote Angkor Wat and NagaWorld developments as the twin tourism icons of Cambodia,” matches the accepted preservational goals of heritage management. In March 2021, in what the Cambodian press called a “surprise move” after strenuous international objections to the project from UNESCO,[15] Cambodia’s Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts rejected the mega-resort’s design proposal.[16] NagaWorld’s chief executive, Tim McNally, responded that they “coordinate closely with key representatives of the government of Cambodia,” and that it would develop an acceptable plan. “Our goal is to enhance and maximize tourism as a growth business sector.”[17]

Despite this setback for the plan, the company’s 50-year lease from the Cambodian government makes it likely that benefits and perquisites accruing to Cambodia’s military and political elite will remain the key determinants in making heritage policy in Angkor.[18] In 2019, tourist revenues from Angkor Wat’s ticket sales alone amounted to $100 million dollars.[19]

Given UNESCO’s lack of any effectual controls over its member states, the organization has little or no ability to send a message to Cambodian authorities that will curb its aggressive capitalization of heritage.

Among the most disturbing elements of Cambodia’s heritage policy are the consequences to the local population, who many heritage professionals have described as ‘victims’ of Angkor’s transformation into one of the most famous world tourist destinations. Angkor Archeological Park is home to over 100,000 people in 112 historic settlements. As noted on the UNESCO World Heritage Angkor page, “the local population, [is] known to be particularly conservative with respect to ancestral traditions and where they adhere to a great number of archaic cultural practices that have disappeared elsewhere. The inhabitants venerate the temple deities and organize ceremonies and rituals in their honor, involving prayers, traditional music and dance.”[20]

Angkor Wat, tourists at sunset, Photo Gerd Eichmann, 1 February 2007, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

These traditions are now threatened. In A Future in Ruins, archaeologist Lyn Meskell cites to Keiko Miura’s extensive documentation of the “demolition of houses, thefts, intimidation and violence” by APSARA’s own police force. She states, “Along with forcible relocation, there are regulations on the construction of new houses, land clearance, cultivation, management of animals and harvesting of forests products… customary practices and even religious ones were forbidden and basic human rights impinged upon.”[21], [22]

This abuse of the local population through “heritage management” for patently self-serving financial interest has direct bearing on the Cultural Property Advisory Committee’ decision-making. CPAC has both the independence and the legal obligation to investigate whether Cambodia’s ‘self help’ policies are actually in compliance with the requirements of U.S. law. It is hardly an example of “self-help” to design “cultural preservation” to enrich private investors in tourism – at the expense of the living cultural and religious traditions of Cambodia’s poorer citizens and while abusing their basic human rights.

Stone Temple Diplomacy and Preah Vihear

Map of Cambodia and Thailand, showing the location of the Preah Vihear Temple, which both countries lay claim to, 16 October 2008. US Central Intelligence Agency Worldbook.

What is the real purpose for U.S. State Department cultural agreements with Cambodia? There appear to be political and economic drivers behind cultural relations with Cambodia that have nothing to do with the CPIA’s purpose and mandate. An example from 2008-2009, when the U.S. was still an active member of UNESCO,[23] shows how political and economic goals intersect with U.S. heritage policy with Cambodia and its neighbor, Thailand.

These appear in the controversial history of the inscription of the Preah Vihear temple on the World Monuments List. Preah Vihar is an 11th c. monument situated in a mountainous region of the Thai-Cambodian border that is disputed territory between the two nations.

Cambodia nominated the temple as a World Monument for UNESCO listing; it was added in July 2008 despite objections from Thailand. Border incidents with the Thais broke out immediately in response. Thai soldiers occupied a temple 150 km to the west, while the Cambodian army occupied another temple nearby. However – this apparent regional tussle over a UNESCO inscription and the control of three remote temple sites was directly linked to the prospect of enormous American investments in an area of overlapping claims to vast natural gas fields in the Gulf of Thailand and to entry of major companies including Boeing, Nike, McDonald’s and Marlboro in the Cambodian market.[24]

Prasat Preah Vihear, photo Gonzo Gooner, 4 April 2011, CCA 3.0 Unported license.

But World Heritage inscription of the relatively obscure temple site of Preah Vihear had even broader international economic and diplomatic repercussions. Both China and the U.S. were on the International Coordinating Committee for Preah Vihear in 2008, when China was heavily invested in mining and industry nearby, paid $290 million dollars toward building a road between Preah Vihear and Angkor – and also built a railway to a northern port. The massive diplomatic investment in inscribing Preah Vihear by China, the U.S., Thailand and Cambodia was ostensibly about cultural relations but, as set forth in the leaked cables, far more linked to U.S. concerns about China’s increasing influence through its “blank check diplomacy” and its mining interests, and in firming up prospects for U.S. arms sales to Thailand “with sales worth US $2 billion then in process.”[25]

In deliberately placing the original administration of CPAC outside of the Department of State, Congress wanted to avoid the use of art and culture as a political tradeoff – or a Band-Aid to cover over and soothe larger diplomatic interests. In setting forth specific requirements that requesting countries had to meet, Congress sought to eliminate U.S. diplomatic and economic considerations that have nothing to do with archaeological preservation or stemming looting or ensuring the UNESCO Convention’s goal that the lawful circulation of art should act as a force for education and peaceful cooperation.

In 2022, courts in Phnom Penh jailed dozens of Cambodian opposition figures. US-Cambodian lawyer Theary Seng (dressed as Lady Liberty) and other government critics were sentenced to years in prison on charges of treason and incitement. VOA photo.

Cambodia is precisely the sort of country the drafters of the CPIA were concerned about. It has an authoritarian government run by an ex-Khmer Rouge military commander, who is a close ally of China’s communist government, and it makes explicit use of its cultural heritage for domestic and international political purposes.

As Freedom House makes clear,

“Cambodia’s political system has been dominated by Prime Minister Hun Sen and the Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) for more than three decades. While the country conducted semicompetitive elections in the past, the 2018 polls were held in a severely repressive environment. Since then, Hun Sen’s government has maintained pressure on opposition party members, independent press outlets, and demonstrators with intimidation, politically motivated prosecutions, and violence.”[26]

Freedom House, Freedom in the World 2021, Cambodia.

Theary Seng is hustled out of court by police enroute to prison. VOA photo.

Despite these obvious problems, the State Department, the Cambodian Government, and an archaeological advocacy group, the Antiquities Coalition, appear to assume that a renewal of the current MOU with Cambodia is a done deal. Indeed, virtually automatic renewals with all of the 29 countries that have cultural property agreements with the U.S. have become routine, raising serious questions whether CPAC meetings and public comment are just for “show.”

In light of the secret negotiations exposed by WikiLeaks, the extremely high-stakes military and economic realities into which cultural heritage decisions factor, it’s clear that CPAC should ensure that its recommendations follow only the original legal structure and definitions mandated by Congress. Unless it does so, the Committee risks becoming a rubber-stamp for State Department goals it is not even aware of and it places its own purpose and function in jeopardy.

The complex history of the Cambodian art market

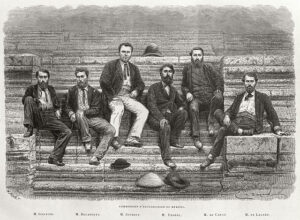

Commission de l’exploration du Mékong à Angkor Wat, 1866, unknown engraver after Emile Gsell, from Voyage d’exploration en Indo-Chine vol. 1 f.p. 26, 1863, Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

The international market for Cambodian artifacts was most active in two distinct periods – under French Indochinese colonial rule and in the period of continual strife under successive states of Khmer Rouge rule and widespread civil unrest from the 1970s to the early 2000s.

Today, France and Belgium remain popular marketplaces for Khmer artworks due to their association with France’s colonial past and the encouragement given to promoting Khmer art in Europe by the École française d’Extrême-Orient (EFEO).

The EFEO or French School of Asian Studies in the early 20th c. was founded in 1898 in Saigon as the Mission archéologique d’Indo-Chine. It was very actively engaged in promoting both archaeology in Cambodia and the appreciation of Cambodian art in Europe.[27] The EFEO held a number of auctions of statues in a luxury hotel Phnom Penh in the 1930’s specifically to increase museum placement and appreciation for Khmer art in Europe. The Conservation d’Angkor maintained a depot where hundreds the most exceptional objects, from heads to complete sculptures were stored and many sent on to French Museums.

Betsy Westendorp-Osieck (1880-1968) and Herman Karel Westendorp (1868-1941), photo Jacob Merkelbach, Wikimedia Commons.

(While Cambodian authorities have long sought the return of hundreds of Cambodian objects from Angkor and other sites from French museums that were shipped there “on loan” decades before, returns of these objects are not presently contemplated by France.)

The EFEO also arranged direct sales, as documented in the purchases on site of four exceptional stone sculptures from Angkor for the Royal Asian Art Society in the Netherlands (Koninklijke Vereniging van Vrienden der Aziatische Kunst’, KVVAK) by its President, Herman Karel Westendorp in 1930.[28]

While a significant number of Cambodian sculptures were exported under French colonial rule, for the most part, the art and artifacts acquired by U.S. private collectors and museums were either purchases of early exports in European secondary markets or of objects removed from Cambodia during the rule of the Khmer Rouge.

It is well-documented that soldiers from the genocidal regime murdered and starved approximately two million Cambodians, a third of the country’s population, in the “killing fields.” The Communist regime also alternately “shot up” statuary and temples with automatic weapons – and looted and trafficked artifacts to Thailand. In much of the world, international collecting of Cambodian art was considered the only available means of preserving it and making it public.

Procession of figures at Angkor Wat in an antique postcard, circa 1900, Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

Brad Gordon, the Cambodian Ministry of Culture’s chief legal counsel, has told the BBC that the trade in these items “could be considered a war crime.”[29] Certainly it was a crime, but it was a crime committed by the then government of Cambodia. Such statements cover up the fact that it was the Khmer Rouge that both perpetrated the destruction and profited by it, that subsequent governments and their high level military continued the practice through at least the 1990s… and that many of the same “criminals” hold high office in Cambodia today.

There is no market for looted Cambodian art in the U.S. today.

The Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara Seated in Royal Ease, Angkor period, late 10th–early 11th century,

Thailand or Cambodia, courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Irrespective of the U.S. agreements with Cambodia, which have been in place since 1999, the status of Cambodian objects in the U.S. is now more carefully scrutinized than any other category of antiquities. This is not primarily a result of the MOUs, which do not apply to objects imported prior to 1999. It is rather as a result of a decade of international media focus on antiquities smuggling, and most recently on the illicit activities of the most prolific SE Asian antiquities dealer of the 80s and 90s, the late British-Thai citizen, Douglas Latchford. A significant number of objects from U.S. private and public collections that passed through Latchford’s hands have been claimed by Cambodia, and in most cases voluntarily returned to Cambodia once informed of their origin.[30], [31], [32]

Latchford, although now regarded as a notorious temple robber, was intimate with Cambodian officials and its cultural ministry, who honored him publicly for his donations of art and financial contributions to the National Museum. Cambodian cultural officials who are still in office today requested that Latchford compile, research, and publish a comprehensive database of Cambodian art in foreign collections, an eight year-long project. His books, which cultural officials are now using to claim items, were first presented with great ceremony to members of the Cambodian royal family.[33] The Cambodian government awarded Latchford a Grand Cross of the Royal Order of Monisaraphon in 2008; it also offered him Cambodian citizenship.[34]

The CPIA’s requirement that the U.S. be a significant market and that a U.S. MOU be part of a “concerted international response” is not met.

MOUs must be based upon a current U.S. market for the specific types of objects listed on a Designated List, not a market that existed 20-70 years before. While instances of looting in Cambodia from the 1970s-1990s are frequently cited in the media, there is no publicly available documentation of current pillage for a U.S. market in Cambodia. Nor has U.S. Customs provided documentation of imports of recently pillaged artifacts from Cambodia.

A review of U.S. online records shows that there is no U.S. auction market for anything but very well provenanced Cambodian art.[35] In comparison, there is a very active auction market in Hong Kong for Khmer gold and other smaller objects from Southeast Asian collections.[36]

The law does not permit an overbroad Designated List.

Silversmith working in repoussé, Cambodia circa 1930 CCA 4.0 International license.

An overbroad MOU that prohibits the circulation of duplicative objects long outside of archaeological context will discourage the independent research, study, and presentation of Cambodian art and artifacts and will not be “consistent with the general interest of the international community in the interchange of cultural property among nations for scientific, cultural, and educational purposes,” the fourth required declaration.

Under the CPIA, the CPAC committee was tasked not only to determine whether requests for MOUs met all four of the fundamental criteria under the Cultural Property Implementation Act, but also to provide expert review of the types of objects covered by import restrictions in the Designated Lists. CPAC should follow the law and not be dissuaded from requiring evidence of illicit trafficking for items on the current designated list or from determining what “self-help” measures were – and will be – expected of Cambodia.

Silversmith working in repoussé, Cambodia circa 1930 CCA 4.0 International license.

A Designated List published by the Department of Homeland Security contains the current list of restricted Cambodian items.[37] Restricted archaeological items date from the Bronze and Iron Ages (1500 B.C. – 550 A.D.) through the Khmer Era (16th c. A.D.) currently include categories of artifacts made from stone, metal, ceramic, glass, and bone. This list has grown dramatically over time, often without expert input from CPAC.[38],[39] [40] The agreement was amended and extended in September 19, 2013[41] and extended again, on September 19, 2018.[42] The most recent request from Cambodia for 2023 apparently now seeks restrictions on common ethnographic art and jewelry made up to 1891, including from ethnic and religious minority cultures found in both Cambodia and surrounding countries.[43]

This is particularly absurd in the case of beads, jewelry, and especially coins, the majority of which were not produced locally and all of which circulated regionally throughout Southeast Asia.

In contrast to the broad restrictions that have been promulgated, the governing U.S. law, the CPIA, only allows restrictions to be put in place on items of “cultural significance” first discovered within, and hence subject to Cambodia’s export control which were exported from Cambodia after the date any restrictions were first imposed.[44] While stone statuary and architectural elements are clearly of cultural significance, many of other objects such as small bronze articles and statues, pottery, cooking utensils, beads and jewelry are not.[45]

Has Cambodia met Benchmarks for Self-Help Measures?

Before any MOU with Cambodia may be extended, CPAC must advise whether “Cambodia has taken measures consistent with the Convention to protect its cultural patrimony.” [46] The CPIA further requires a finding that “remedies less drastic than the application of the restrictions . . . are not available.”[47]

Angkor Wat, Photo Gerd Eichmann, 1 February 2007, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Here, there is reason to believe that the Cambodian government has not done all it can do to protect its own cultural patrimony. While Cambodia reports $2.5 billion in earnings from tourism[48] with Angkor archaeological park reaping an astonishing $75.7 million in ticket sales for the first nine months of 2017 alone,[49] and $100 million in 2019,[50] it is unclear how much money the Cambodian government itself (as opposed to foreign donors) actually spends on protecting its cultural patrimony. According to the Phnom Penh Post, “Cambodia has long relied on foreign countries and donors to support international excavation projects and shows little sign of taking on more funding responsibility.”[51] Nor is it clear whether foreign archaeological missions pay their workers a fair living wage or take advantage of modern electronic surveillance systems to monitor their sites for looting in the long off season. For that reason, consistent with Congressional directives, GHA and CCP request CPAC to seek information on these issues and to condition any further renewals on Cambodia surpassing ascertainable benchmarks in these areas.

There are also persistent allegations that elements within the Cambodian military continue to loot out of the way temple complexes of statuary with the help of government heavy equipment.[52] While U.S. collectors and museums are no longer collecting such materials, CPAC should be given assurances that the Cambodian government is taking an active stand against looting for other markets.

The general interest of the international community in the interchange of cultural property among nations for scientific, cultural, and educational purposes… is not served by a Cambodian MOU.

Artifacts at the National Museum of Cambodia

28 August 2022, Photo Satdeep Gill, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

In light of the political and economic concerns raised above, it should be clear that a renewal of the U.S.-Cambodian MOU would not be “consistent with the general interest of the international community in the interchange of cultural property among nations for scientific, cultural, and educational purposes…” The Cambodian government has failed to move forward to expand cultural exchanges, as set forth in Article II of the 2008 and 2013 MOUs. These requirements were established primarily to remedy perceived deficiencies by the Cambodian government in meeting the criteria under the statute. These were crucial undertakings, necessary to safeguard the American public’s access to Cambodian heritage through educational exchange and long and short term museum loans, and to demonstrate the Cambodian government’s commitment to build the capacity of its museums to care for, document and protect the cultural heritage of Cambodia.

It is a key principle of global access that if objects are not allowed to travel, then they must be accessible not only to the well-funded researchers who are privileged to travel to Cambodia, but also to students, scholars, collectors and museums worldwide. Between the signing of the 2013 MOU and its renewal in 2017, there was one, 3½ month long exhibition, “Lost Kingdoms: Hindu-Buddhist Sculpture of Early Southeast Asia, 5th to 8th Century”[53] in 2014 at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, with 22-24 objects on loan from Cambodia.

Artifacts at the National Museum of Cambodia

28 August 2022, Photo Satdeep Gill, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

The only exhibition actually based on artifacts from Cambodian museums that has recently come to the U.S. is the international touring exhibition Angkor: The Lost Empire of Cambodia. The exhibit was not produced by Cambodian museums, but by MuseumsPartner, a commercial producer of international traveling exhibitions, providing logistics and art shipping, handling, crating and storage. The exhibition, which is geared to science and natural history museums, features interactive exhibits and 120 ancient artifacts originally from Cambodia – half from international collections and half from Cambodia, and an iMAX film on Angkor.

A 2022 digitally-based exhibit with a similarly interactive focus was organized by the Cleveland Museum of Art “Revealing Krishna: Journey to Cambodia’s Sacred Mountain” with the cooperation of Cambodia’s National Museum and the Musee Guimet in Paris. The exhibition was recently adapted by the National Museum of Asian Art in a show April-September 2022.[54]

Under these circumstances – and given Cambodia’s history of early 20th C. government sponsored sales and later 20th C. government-participation in site destruction and smuggling art to Thailand, the media’s characterization of all Cambodian art as “looted” and improperly exhibited in U.S. museums is ludicrous. Nor is the Cambodian government’s position “consistent with the general interest of the international community in the interchange of cultural property among nations for scientific, cultural, and educational purposes.”

Artifacts at the National Museum of Cambodia

28 August 2022, Photo Satdeep Gill, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

A paltry cultural outreach by the Cambodian government cannot compensate for the loss of access by U.S. citizens to the art of Cambodia through U.S. museums. Moreover, the 2020 U.S. census identified 339,000 persons of Cambodian background living in the United States. Continuing and even expanding restrictions will particularly harm U.S. museums in their educational role as the primary institutions responsible for introducing Cambodian-Americans and their children to art that is both their own and America’s heritage.

Furthermore, the information now accessible through Wikileaks has shown that cultural engagements within the Department of State specific to Cambodia have been profoundly impacted by diplomatic, economic and domestic Cambodian political agendas that have nothing to do with the goals of the Cultural Property Implementation Act.

Artifacts at the National Museum of Cambodia

28 August 2022, Photo Satdeep Gill, CCA-SA 4.o International license.

By initially placing the administration of the CPAC under supervision of United States Information Agency and not the Department of State, Congress hoped to avoid the politicization of cultural property agreements and their use for purposes other than to stem the loss of precious archaeological resources – in countries where all four legal determinations are met. Any import restrictions should be applied prospectively and not as embargoes, as the law requires. Cambodia should also be required to issue export permits for ancient and ethnographic items whose local circulation – and sale to Thailand’s even more active tourist markets – has been winked at throughout the 24 year long duration of the MOU by officials and military who profit by this commerce.

It is hoped that CPAC will exercise its due diligence to conform any extension of Cambodian restrictions to the limitations imposed by Congress and U.S. law – not to expand unnecessary and unjustified restrictions even further by including ethnological items and minor and duplicative materials for which there is neither legal nor common-sense justification.

[1] This article is based in part on the written testimony on the Cambodian MOU submitted to the Cultural Property Advisory Committee at the Department of State drafted jointly by Global Heritage Alliance, 5335 Wisconsin Ave., N.W., Suite 440, Washington, D.C. 20015. http://global-heritage.org, and the Committee for Cultural Policy, Inc., POB 4881, Santa Fe, NM 87502, https://culturalpropertynews.org/, [email protected].

[2] 19 U.S.C. §§ 2601 et seq

[3] Id. § 2601 (2).

[4] Id. § 2602 (a) (1).

[5] Id.

[6] As the Senate Committee Report explains, “The Committee intends these limitations to ensure that the United States will reach an independent judgment regarding the need and scope of import controls. That is, U.S. actions need not be coextensive with the broadest declarations of ownership and historical or scientific value made by other nations… U.S. actions in these complex matters should not be bound by the characterization of other countries, and these other countries should have the benefit of knowing what minimum showing is required to obtain the full range of U.S. cooperation authorized by this bill.” Senate Report 97-564 at 6 (1982).

[7] Hun Sen was formerly a Communist Party of Kampuchea (បក្សកុម្មុយនីស្តកម្ពុជា/CPK; “Khmer Rouge”) Battalion Commander. According to the Hun Sen Wikipedia page, he defected in 1977 and fought with Vietnamese forces in the Cambodian–Vietnamese War. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hun_Sen.

[8] Recent, drastic amendments to Cambodia’s Constitution “represent an attempt by Hun Sen to wrap his plans for dynastic succession – in which he will hand over power to his eldest son, Hun Manet – in constitutional protections, and constitutional legitimacy.” Benjamin Lawrence, ConstitutionNet, 28 September 2021, https://constitutionnet.org/news/cambodias-constitutional-amendments-consolidating-control.

[9] David Boyle, “Opposition Vanquished, Cambodia’s Hun Sen Turns Attention to Legacy,” Voice of America, December 8, 2017, https://www.voanews.com/a/opposition-vanquished-cambodias-hun-sen-turns-attention-to-legacy/4155205.html. Kem Sokha was accused of conspiring with US to topple the Hun Sen government. At least 50 more opposition party leaders were jailed after a series of mass trials in 2022, characterized by Human Rights Watch as entirely without evidence.

[10] Matthew Galway, “Dictatorial Devarāja: Charisma and Autocracy in Cambodian Political Culture and the Rise of Hun Sen, Praxis, June 26, 2022, https://positionspolitics.org/matthew-galway-dictatorial-devaraja-charisma-and-autocracy-in-cambodian-political-culture-and-the-rise-of-hun-sen/.

[11] Id.

[12] Lynn Meskell, A Future in Ruins: UNESCO, World Heritage and the Dream of Peace, Oxford University Press, July 2, 2018, 112. Meskell notes that Norodom Sihanouk a leader in the Khmer Rouge-Republican-Royalist coalition, sought an international campaign to preserve Angkor and cites to Michael Falser’s statement that recognizing Angkor as World Heritage was the idea of the Khmer Rouge exiled in Paris as a means of bolstering their territorial claims. See also Michael Falser, “Representing Heritage Without Territory: The Khmer Rouge at the UNESCO in Paris During the 1980s and Their Political Strategy for Angkor,” in Cultural Heritage as Civilizing Mission, ed. M. Falser, New York, Springer, 2015.

[13] Meskell, A History in Ruins, 113.

[14] Kuch Naren, “Government to take over ticketing at Angkor Wat,” Cambodia Daily, Nove 7, 2015, https://english.cambodiadaily.com/news/government-to-take-control-of-ticketing-at-angkor-wat-99671/

[15] “UNESCO alarmed over NagaCorp scheme near Angkor Wat,” GGRASIA, Feb 19, 2021, https://www.ggrasia.com/unesco-alarmed-over-nagacorp-scheme-near-angkor-wat/

[16] Matt Hickman, “Cambodian government blocks mega-resort development near Angkor,:\” The Architect’s Newspaper, March 26, 2021, https://www.archpaper.com/2021/03/cambodian-government-blocks-mega-resort-development-near-angkor/

[17] “NagaCorp working fresh plans for Angkor Wat: Chairman,” GGRASIA, March 26, 2021, https://www.ggrasia.com/nagacorp-working-fresh-plans-for-angkor-wat-chairman/

[18] Sebastian Stranio, “Cambodia Passes Law to Regulate Gambling Sector,” October 7, 2020, https://thediplomat.com/2020/10/cambodia-passes-law-to-regulate-exploding-gambling-sector/Cambodia had 193 casinos in 2020, exclusively for foreign tourist use.

[19] Voice of America, “Cambodians Revel in Now Tourist Free Angkor Wat,” Voice of America, June 14, 2020, https://www.voanews.com/a/south-central-asia_cambodians-revel-now-tourist-free-angkor-wat/6191082.html.

[20] UNESCO World Heritage Convention, “Angkor,” https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/668/

[21] Meskell, A History in Ruins,” 113, citing Keiko Miura, “Discourses and Practices.” B. Hauser-Schäublin, ed. World Heritage Angkor and Beyond: Circumstances and Implications on UNESCO Listings in Cambodia (Göttingen: Universitätsverlag Göttingen, 2011).

[23] The U.S. withdrew from UNESCO on December 31, 2018, but still maintains contacts through other channels.

[24] While cultural and diplomatic officials in the U.S. and Cambodia denied any connection at the time, Wikileaks revealed 150 diplomatic cables including a number from U.S. Ambassador to Cambodia Joseph Mussomeli to the DoC, DOS, and others about “the pending inscription of Preah Vihear temple on the UNESCO World Heritage List and Cambodia’s bilateral debt with the U.S. Delegation members and the embassy believe that successful resolution of the Preah Vihear issue could open the door to a resolution of the overlapping claims in the Gulf of Thailand.” And continued, “Inscribing Preah Vihear on the UNESCO World Heritage List, if handled correctly, actually could open opportunities for the two countries to work more closely on both cultural issues and the more lucrative issue of the overlapping claims in the Gulf of Thailand.” Meskell, A History in Ruins, 120. As Meskell writes, “Those exchanges reveal that national patrimony is underwritten by, and constituted through, increasingly international arrangements.” Id.

[25] Id. at 121. Lynn Meskell cites here to “Scenesetter for General Casey’s Meeting with Thai Army Commander General Anupong,” dated July 16, 2009, https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/09BANGKOK1720_a.html

[26] Freedom House, Freedom in the World 2021, Cambodia

[27] The original Angkor archaeological park was created under the supervision of the École française d’Extrême-Orient or French School of the Far East. The EFEO established the Angkor Conservancy to manage the site. Due to lack of space, only the finest objects were collected at the Angkor depot; these were subsequently distributed to Hanoi, Phnom Penh, and Paris. William A. Southworth, Provenance of Four Sandstone Sculptures from Cambodia,” 2013, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, 141-171, 146, https://www.academia.edu/79517309/Provenance_of_Four_Sandstone_Sculptures_from_Cambodia.

[28] Id. at 141-171.

[29] Celia Hatton, “The long struggle to return Cambodia’s looted treasures,” BBC News, May 12, 2022, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-61354625.

[30] To give just one example, thirty objects, all of whose owners voluntarily returned them, were turned over by federal officials in New York to Cambodian officials on Aug. 8, 2022. “We commend individuals and institutions who decided to do the right thing,” said Damian Williams, the U.S. attorney for the Southern District, “and after learning about the origin of the antiquities in their possession decided to voluntarily return those pieces to their homeland.” https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdny/pr/us-attorney-announces-return-30-looted-antiquities-kingdom-cambodia

[31] Julia Jacobs and Tom Mashberg, “U.S. Returns 30 Looted Antiquities to Cambodia,” NY Times, Aug 9, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/08/arts/us-cambodia-looted-antiquities.html

[32] According to information from NY legal sources, additional private collectors are currently negotiating with Cambodian authorities to return items they now consider tainted by any past association with Latchford. Private communication from an anonymous legal source, 12/9/2022.

[33] The publications, by Douglas Latchford and Emma Bunker, are Adoration and Glory: The Golden Age of Khmer Art (2003), Khmer Gold Gifts for the Gods (2008), and Khmer Bronzes: New Interpretations of the Past (2011), which provided significant new metallurgical and technical research on Khmer bronze.

[34] Wikipedia, “Douglas Latchford,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Douglas_Latchford.

[35] Sotheby’s auction house offered only three objects for U.S. auction identified as ‘Khmer’ from 2011 to 2017, one with a collection history dating to 1968 and the other two deaccessioned from the Cleveland Museum of Art, both acquired in the 1930s. From 2017 to 2022, Sotheby’s USA has sold four more Khmer sculptures, three with established provenances dating back to the 1960s and one to 1981. The only other Cambodian or Cambodian/Thai Khmer objects sold by Sotheby’s in the US in recent years are common examples of Chinese trade pottery that circulated throughout SE Asia from the last few hundred years, all valued at less than $1000 and available in their ‘buy now” section, not deemed worthy of auction.

[36] See Sotheby’s auction Magnificent Lustre – Southeast Asian Gold Jewellery and Ornaments from an Asian Private Collection 1- 8 September 2022, Hong Kong. https://www.sothebys.com/en/digital-catalogues/magnificent-lustre-southeast-asian-gold-jewellery-and-ornaments-from-an-asian-private-collection. Khmer objects also featured in Sotheby’s Golden Splendour – Gold Jewellery from the Collection of Tuyet Nguyet and Stephen Markbreiter, Hong Kong, 28 July 2021, https://www.sothebys.com/en/buy/auction/2021/golden-splendour-gold-jewellery-from-the-collection-of-tuyet-nguyet-and-stephen-markbreiter.

[37] Cambodia 2008 Revised Designated List Federal Register Notice, September 19, 2008, https://eca.state.gov/files/bureau/cb2008dlfrn.pdf

[38] On December 2, 1999, the U.S. first imposed an emergency import restriction (PDF) on Khmer stone sculpture and architectural elements from Cambodia. Cambodia 1999 Emergency Restriction Designated List, December 2, 1999, https://eca.state.gov/files/bureau/cb1999eadl.pdf

[39] Cambodia 1999 Emergency Restriction Designated List, December 2, 1999, https://eca.state.gov/files/bureau/cb1999eadl.pdf. On September 19, 2003, without submitting the agreement to review of the then sitting CPAC committee, the U.S. and Cambodia entered into a bilateral agreement (PDF), or MOU under the CPIA to impose import restrictions on certain Khmer archaeological materials in stone, metal, and ceramic. CPAC members were informed that a bilateral agreement had been signed with Cambodia without any discussion with the current CPAC members. No review or recommendation was sought from the currently serving members of CPAC, a clear violation of the procedures set forth in the Cultural Property Implementation Act. When asked to account for this failure to follow statutory requirements, CPAC administrator Maria Kouroupas stated that the Cambodian government had now satisfied all the previously unmet (and unspecified) conditions for a bilateral MOU that had caused the 1999 CPAC members to decline to recommend a bilateral agreement. Source: Kate Fitz Gibbon, then a serving member of CPAC. The materials previously protected under the emergency import restriction were subsumed under this agreement, as reflected in the revised Designated List published in the Federal Register on September 22, 2003. Effective September 19, 2008, the two countries extended the agreement for an additional five years and amended it to apply U.S. import restrictions to archaeological material dating from the Bronze Age to the end of the Khmer Empire. The Designated List was revised again to reflect this amendment on September 22, 2008.

[40] See Cambodia 2008 Revised Designated List Federal Register Notice, September 19, 2008, https://eca.state.gov/files/bureau/cb2008dlfrn.pdf.

[41] See Extension of Import Restrictions Imposed on Archaeological Material From Cambodia From the Bronze Age Through the Khmer Era, September 16, 2013, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2013-09-16/pdf/2013-21803.pdf

[42] See Extension of Import Restrictions Imposed on Archaeological Material From Cambodia, September 19, 2018, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2018-09-19/pdf/2018-20316.pdf.

[43] The restricted list requested by Cambodia has been expanded in 2023 to include ethnological material dating from AD 1400 through 1891, and includes architectural elements from religious buildings (e.g., wooden doors and carved panels); sculpture (e.g., wooden figures and often decorated with lacquer, gold leaf, paint, and/or incrustations of glass); manuscripts (e.g., handwritten works on paper and/or palm leaf); funerary objects (e.g., ceramic or stone urns or wooden urns); and religious objects (e.g., bells, chariot fixtures, popil, musical instruments, and betel containers often made from bronze). https://eca.state.gov/highlight/cultural-property-advisory-committee-meeting-January-30-February-02-2023

[44] 19 U.S.C. §§ 2601, 2604, 2606.

[45] CPAC should not conflate “archaeological interest” with “cultural significance.” Objects of “archaeological interest” still must be of “cultural significance” to be restricted. 19 U.S.C. § 2601 (2).

[46] 19 U.S.C. § 2602 (A) (1) (B).

[47] Id. § 2602 (A) (1) (C) (ii).

[48] “Cambodia Earns $2.5 bn from Tourism”, Bangkok Post (April 15, 2014), available at http://www.southeastasianarchaeology.com/2014/04/15/cambodia-reports-2-5-billion-earnings-from-tourism/

(last visited December 8, 2022).

[49] “Cambodia’s famed Angkor earns nearly 76 mln USD in 9 months,” Xinhua/English.news.cn (Oct. 1, 2017), available at http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2017-10/01/c_136653210.htm (last visited December 8, 2022).

[50] Voice of America, “Cambodians Revel in Now Tourist Free Angkor Wat,” Voice of America, June 14, 2020, https://www.voanews.com/a/south-central-asia_cambodians-revel-now-tourist-free-angkor-wat/6191082.html.

[51] Annie Lee, “Archaeology gets education boost, but pay remains poor,” The Phnom Penh Post (July 1, 2014), available at http://www.phnompenhpost.com/lifestyle/archaeology-gets-education-boost-pay-remains-poor (last visited December 8, 2022).

[52] Simon Makenzie and Tess Davis, Temple Looting in Cambodia, 54 Brit. J. Criminol. 722, 729-30 (2014). (“In late 1998, rogue Cambodian military surrounded the temple at dawn and blockaded it from the local community, with no explanation. The Cambodian generals responsible no doubt used the country’s ongoing tumult to their advantage, as the Khmer Rouge was disintegrating near simultaneously, just 130 km away from Banteay Chhmar in Anlong Veng. For the next two weeks, heavy machinery was used to break up the complex and when the clamour finally stopped, soldiers loaded an estimated 30 tons of stone—including an entire 30 m of the southern wall, prized for its skilled bas-reliefs of Lokeshvara and Apsaras—onto six trucks and drive off for the Thai border just 15 km away…. While scholars and journalists have described the 1998 heist as unprecedented, we learned instead that it is fairly representative of the history of looting at Banteay Chhmar and just the tip of the iceberg in terms of looting across the country.”).

[53] See: Lost Kingdoms: Hindu-Buddhist Sculpture of Early Southeast Asia, 5th to 8th Century, https://www.metmuseum.org/press/exhibitions/2014/lost-kingdoms.

[54] The Cleveland Museum of Art, “Revealing Krishna: Journey to Cambodia’s Sacred Mountain, “https://www.clevelandart.org/exhibitions/revealing-krishna-journey-cambodias-sacred-mountain

At Angkor Wat, 5000 Buddhist monks, plus actors, scouts, and dancers celebrated Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen's "victory" over jailed opposition in 2017. VOA screenshot.

At Angkor Wat, 5000 Buddhist monks, plus actors, scouts, and dancers celebrated Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen's "victory" over jailed opposition in 2017. VOA screenshot.