“I would like to underscore that Ukraine is not just a neighboring country to us, it is an inherent part of our own history, culture, spiritual space… Ukraine has never had stable traditions of their own statehood.”

Speech by Russian President Vladimir Putin 21 February, 2022, after a UN Security Council meeting and just before the invasion of Ukraine.[1]

“The occupiers have identified culture, education and humanity as their enemies.” Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, May 20, 2022, after bombing of Palace of Culture in Lozova in Kharkiv.[2]

Ivankiv Historical and Local History Museum (Kyiv region) after Russian shelling on 25 February 2022 Author Ministry of Culture and Information Policy of Ukraine, CCA 4.0 license.

One of Russia’s first actions in its invasion of Ukraine was to burn a small folk art museum to the ground.[3] While other nearby buildings were untouched, the museum was destroyed.

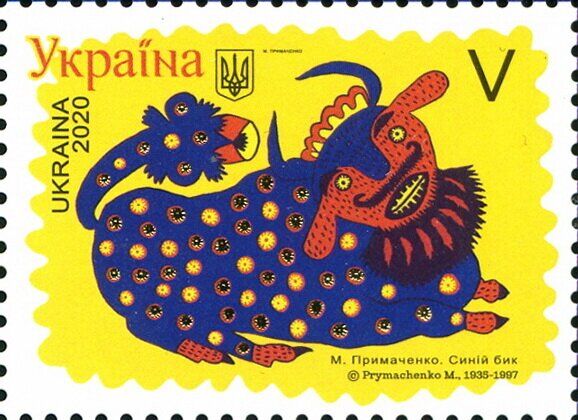

Why target this particular museum first? The Ivankiv Museum was home to the works of celebrated folk artist Maria Oksentiyivna Prymachenko. Long after her death in 1997, Prymachenko is still a powerful symbol of Ukrainian identity – UNESCO declared 2009 “the year of Prymachenko,” and a street in Kiev was named after her. The people of Ivankiv valued Prymachenko’s work; ten of her artworks were saved by a local man who risked his life to rescue them from the museum as it burned.

In Ukraine, folk art has long been seen as a tangible expression of its national independence. The flowering of Ukrainian folk art went hand-in-hand with other European artistic experimentation in the early 20th century. It was less concerned with industrialization than other modern movements; in Ukraine, it took on the characteristic of a national movement distinct from Russian culture. Folk art was a discreet expression of national cultural identity opposed to that of Russia and folk artists were involved in independence movements, particularly after the Soviet collectivization and denial of food to Ukraine resulted in the Holodmor famine of 1932-33 in which millions starved to death.

Mariya Oksentiyivna Prymachenko. In 1966, Prymachenko was awarded the Taras Shevchenko National Prize of Ukraine.

The torching of the Ivankiv Museum was a signal to the Ukrainian people that Russia denied their identity and their independence. It also erased any pretense that Russia would adhere to international conventions on cultural heritage; Russia deemed its responsibility to protect objects, monuments, and cultural institutions in Ukraine only as they were connected to its own Russian heritage; similarly, thefts from Ukrainian museums were justified because whatever treasures Russia took from Ukraine were Russia’s to ‘protect.’

The destruction of the Ivankiv Museum was neither an isolated nor a random incident. Long before its military invasion, Russia has been waging a well-calculated propaganda campaign directed specifically at damaging Ukrainian civic life and cultural identity. The campaign, which involved replacement and construction of monuments and reframing historical narratives to denigrate Ukrainian independence had been part of Russia’s proxy war in Donetsk since 2014. During the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, Russian resources were specifically directed against Ukrainian cultural assets and to eliminating the most familiar local expressions of civil life: libraries, schools, hospitals, marketplaces and city centers, monuments, and museums.

Documenting heritage for reconstruction and rebuilding – and to make cases for Russian war crimes.

There are many examples in the Ukrainian war of the destruction of museums and cultural institutions, seizures of artworks to be carried off to Russia, and replacement of monuments to one nation’s past with another’s. These are not simply collateral damage, isolated incidents or accidents of war. They are important elements of a Russian propaganda campaign to redefine Ukraine’s identity and retell its history.

Kurgan, archaeological site now recorded as being destroyed. Ukrainian database of sites damaged or destroyed.

By the end of June 2022, a Ukrainian government website hosting a database of war crimes[4] against cultural sites listed descriptions and photographs of over 450 antique buildings, theaters, monuments, churches, archaeological and other sites that been damaged, collating Russia’s actions in violation of the 1954 Hague Convention.

Sacred sites appear to be particularly targeted. Russian shelling of churches and monasteries cause as much distress as the loss of their homes among Ukraine’s older and village populations. By the end of May 2022, UNESCO had recorded damage to 62 religious sites. Information on damage is compiled as it reaches Ukrainian and international organizations through various media. News often comes through crowdsourcing and then makes its way to databases. For example, the Art Newspaper reported damage to the Holy Dormition Sviatohirsk Lavra and destruction of its St. George Skete via photos shared on Facebook by a Ukrainian military officer.[5]

Serhiy Laevsky – Chernihiv Regional Library.

International organizations have been very active documenting damage and destruction of museums, churches and other places of worship, markets and communal spaces, schools, and hospitals – public spaces making up the essentials of civic life. Different organizations are tracking damage for different categories of loss. The International Alliance for the Protection of Heritage in Conflict Areas (Aliph) and the Heritage Rescue Emergency Initiative (Heri) are tracking data on damage to sites.

The Smithsonian Cultural Rescue Initiative and Cultural Heritage Monitoring Lab (CHML) at the Virginia Museum of Natural History in Martinsville recently released a one-page summary report[6] on information gathered about 26,000 cultural heritage sites in Ukraine through satellite imagery. The brief report stresses the need for on-site partners to do structural assessments to truly measure the damage.

The International Council of Museums (ICOM), the World Customs Organization, border police, Interpol, and UNESCO are joining efforts to prevent cross-border transportation of stolen objects and preparing informational materials for law enforcement, but this cannot deter the chief criminal, Russia, from seizing Ukrainian artworks from areas under its control and moving them across its border.

Russian missle strike on House of Culture in Park.

In May 2022, a shipment of early medieval jewelry objects of bronze that was mailed to the UK was intercepted by British authorities. They will be exhibited at the British Museum until it is safe to return them to Kyiv.[7] In June, Ukrainian authorities raided a Kyiv office associated with a former Ukrainian lawmaker who also served as an official in Crimea before it was annexed. They seized “more than 6,000 antiquities, including swords, sabers, helmets, amphoras and coins,” the largest seizure of antiquities ever in Ukraine, according to Prosecutor General Iryna Venediktova.[8]

Collectively, the coordinated destruction of civil life has already prompted allegations that Russian actions in Ukraine raise a very serious risk of genocide, according to the New Lines Institute for Strategy and Policy and the Raoul Wallenberg Centre for Human Rights.[9]

Ukrainian museum director and curator kidnapped to find art.

Gold Scythian ceremonial helmet and pendant, courtesy Allard Pierson Museum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Melitopol’s mayor announced on April 30, 2022 that Russians had removed the most valuable holdings of the Melitopol Museum of Local History, its collection of Scythian gold. Ukrainian museums possess some of the most outstanding examples of Scythian gold in the world and the Melitopol collection held some of the finest among them.

In March, Russian troops had forced their way into the home of Melitopol Museum director Leila Ibrahimova, put a hood over her head and kidnapped her. They interrogated her for hours, then finally released her. She fled Melitopol soon after, but a few weeks later received a call from Galina Andriivna Kucher, a curator at the museum. Kucher told

Ibrahimova that a man in a white lab coat accompanied by Russian soldiers had come to her home and taken her at gunpoint to the museum, demanding she show them where the collections were. She refused to tell them, but they had searched together with a new museum director, Evgeny Gorlachev, appointed by the Russian military and finally found the hidden boxes, taking almost 200 gold items and other objects. A Russian film crew recorded the theft.[10] Kucher, a well-respected, 60-year old academic, was briefly released, but after news of the theft from the museum was announced in Western media, she was kidnapped again by soldiers from her home. There has been no word from her since.

Galina Kucher, a curator at the Melitopol Museum of Local History. She has not been heard from since she was kidnapped by Russians for the second time. Photo via Facebook.

In the city of Mariupol, site of some of the fiercest fighting in the war, its city council announced in April that Russian forces had taken more than 2,000 exhibits from Mariupol museums and transferred them to Donetsk. The Mariupol local history museum was bombed and almost entirely destroyed.[11] The Arkhip Kuindzhi Art Museum was located in an Art Nouveau landmark, and dedicated to the Ukrainian Realist painter who was for a time associated with Ilya Repin and the Wanderers group. The Kuindzhi museum was destroyed in an airstrike on March 20.[12] On the same day, Russia bombed Mariupol’s G12 art school, where 400 civilians had taken refuge in basement shelters. Four days before, the Donetsk Regional Theatre of Drama was shelled, where an estimated 1300 elderly, women, and children were hiding. Only 130 are thought to have survived.[13]

Even before the Melitopol and Mariupol thefts by Russian forces, Ukrainian museum professionals such as Olesia Ostrovka-Liuta, director of Art Arsenal cultural center in Kyiv, were sending a clear message to fellow museum professionals that the Russian invasion was an “assault on culture” that was “genocidal in its intent.” She told an international webinar for museum leaders organized by the National Museum of American Diplomacy that heritage workers were in similar danger as civil activists and journalists because of their work to preserve Ukrainian cultural identity.[14] Ukrainian archaeologist Oleksandr Symonenko told the NY Times, “The Russians are making a war without rules. This is not a war. It is destroying our life, our nature, our culture, our industry, everything. This is a crime.”[15]

Russian museum directors support Putin’s war

A number of key contemporary art figures in Russia, some of them foreigners, have taken public positions against the invasion of Ukraine. In March 2022, State Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts deputy director Vladimir Opredelenov announced that he was leaving the museum due to his failure to see eye to eye with museum colleagues on current world events. VAC Foundation artistic director Francesco Manacorda told ARTnews he was resigning because of the conflict in Ukraine. Simon Rees, artistic director of the Cosmoscow art fair resigned immediately after the invasion, on February 24, and is now working in Vienna assisting in Ukrainian refugee resettlement.[16]

Aleksandr Shkolnik was honored by President Vladimir Putin for his contribution to “patriotic education” Photo: Mikhail Metzel, TASS

Others, including the directors of some of Russia’s most established museums, have expressed wholehearted support for Putin and explicitly supported Russian actions. Hermitage director Mikhail Piotrovsky referred to the suspension of relations by Western museum partners as cancellation of Russian culture. His statement followed a familiar Russian propaganda approach, accusing the West of continuing colonialism and Western resentment of Russia to the “culture of guilt and repentance for guilt” of the Black Lives Matter movement. Pietrovsky described himself and the Hermitage as a part of Russia’s inevitable success through retaking former territories. He described Russian loans to foreign museums as “a powerful cultural offensive. If you want, a kind of ‘special operation’, which a lot of people don’t like. But we are coming. And no one can be allowed to interfere with our offensive.”[17]

Museum directors and cultural heads inside Russia have in some cases been sanctioned by European nations. Both Australia and the UK issued sanctions against Aleksandr Shkolnik, a Putin supporter and director of Moscow’s Museum of the Great Patriotic War, for “supporting and promoting the Government of Russia’s false narrative that the invasion of Ukraine is an exercise of ‘de-Nazification’,” an action which could “threaten the territorial integrity, sovereignty or independence of Ukraine.” Shkolnik said he was proud to be sanctioned because, “The hour will come when Ukrainian neo-Nazis will be condemned, as was the case at the end of World War II.”[18]

Ukrainian responses to militaristic statements by Russian cultural authorities stressed the importance of art to Ukrainian independence. “With each invasion, some loss of culture is inevitable,” said Taras Voznyak, director of the Lviv National Art Gallery. “Putin knows that without art, without our history, Ukraine will have a weaker identity. That is the whole point of his war — to erase us and assimilate us into his population of cryptofascist zombies.”[19]

Russia’s Crimean claims and theft of archaeological artifacts

Russia has begun excavations at the ancient city of Tauric Cheronese, Crimea, listed as a Unesco World Heritage site in 2013.

Russia’s political claims to Ukrainian art and history became explicit long before the 2022 invasion. One of the most highly publicized controversies in the annexation of Crimea was Russia’s demand for control of objects loaned before annexation from Ukrainian museums located in Crimea.[20] Less than a year after Russia’s invasion of Crimea and staged referendum, Russian authorities began rapid archaeological digs, many taking place near the building of a highway and bridge linking Sevastopol in Crimea with Russian territory through the Kerch Strait. According to Russian media, one million artifacts have been excavated. The Ukrainian Ministry For The Reintegration Of The Temporarily Occupied Territories Of Ukraine had identified 29 of these illegal and unmonitored excavation as of July 2021.[21] A UNESCO report released that September stated that:

Excavation work at the Kosh-Kuyu settlement near Kerch in November 2017. Institute of Archaeology of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

“Russia has appropriated Ukrainian cultural property on the peninsula, including 4,095 national and local monuments under state protection. Appropriation of monuments is in itself a violation of international law. However, it is equally important that Russia uses such appropriation to implement its comprehensive long-term strategy to strengthen its historical, cultural and religious dominance over the past, present and future of Crimea.”[22]

The UNESCO report specifically identifies Russian attempts to erase the history of Crimean Tatars by, for example, destroying Muslim burial grounds, as a way of justifying Russian annexation of Crimea. The Crimean Tatars are a Muslim people who were the majority population of Crimea from the 10th – 19th centuries, but were forcibly deported under Stalin, killing as many as half of them. The right of return to Crimea for Crimean Tatars became Soviet policy only in 1989.[23]

Friendship monuments removed by Ukraine; monuments to the Wagner Group mercenaries installed by Russia

A month prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a prescient analysis appeared in Small Wars Journal, authored by Damian Koropeckyj, a Senior Analyst at the Cultural Heritage Monitoring Lab (CHML) and a field archaeologist at Historic St. Mary’s City. Koropeckyj identifies two key narratives in Russian Information Operations (IO):

“the portrayal of Ukrainians as neo-Nazis and the framing of the war in the Donbas as a continuation of World War II…”

“the depiction of south and east Ukraine as historically Russian as well as the positioning of Crimea as an ancient Russian land and the cradle of Russian orthodoxy…”[24]

The 16th-century Khan’s Palace in Bakhchisaray is another Crimean historical treasure that could be under threat amid reports of dubious renovation work.

Koropeckyj shows how these two themes are made manifest through [25]Russian use of tangible cultural heritage, a key element of which is monument construction in Crimea and separatist-held territory in the eastern Ukraine. He begins with a poignant example, a statue of Stalin, Roosevelt, and Churchill installed at Livadia Palace, which had been rejected for display in 2005 after protests by Crimean Tatars against the depiction of Stalin, but which was installed in 2015 at a ceremony attended by Director of the Foreign Intelligence Service and Chairman of the Russian Historical Society Sergey Naryshkin and the leader of the Night Wolves, a pro-Russian proxy involved in the annexation of Crimea as well as fighting in Eastern Ukraine. Another monument, to Tsar Alexander II was installed in 2017 at the Livadia Palace, by President Putin in person.

Koropeckyj identifies 91 recent monuments built in Crimea and eastern Ukraine. Different subjects of Russian history are reflected in the monuments. Many recent monument installations are about the defense of the homeland during WWII. A 2021 WWII memorial built in Donetsk juxtaposes the dates of 1941-1945 with that of 2014. The valorization of Russian mercenary activities is seen in the construction of a prefabricated monument to “Russian Volunteers” set up in Luhansk, which is also found at a Wagner Group base outside of Palmyra, Syria.[26]

Scythian amimal-style applique, gold. Allard Pierson Museum photo.

In a recent presentation for the ABA’s Art & Cultural Heritage Law Committee, Dr. Brian Daniels noted that the recent building of pro-Russian monuments in other former Soviet and Baltic countries may be a sort of canary-in-a-coal mine, an indication of future Russian irredentist claims.[27] Dr. Daniels also noted that the destruction of cultural heritage in other nations appears to be following similar patterns. These may involve the targeting of specific cultural sites associated with independence actors and movements, the destruction of civic life to scale, whether it means taking out the bakery, library and church in a village or more wholesale destruction of schools and hospitals as well in a city, and finally, the theft of important artworks for propagandistic purposes by the thieves themselves.

Russia’s military is destroying cultural heritage and civilian infrastructure forbidden by its own rules.

The official “Manual on International Humanitarian Law for the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation” shows that the Russian military is aware that it is violating not only international law, but also Russian law in its destruction of cultural heritage in Ukraine. The 2001 manual states:

“Prohibited methods of warfare include “killing or wounding civilians … taking of hostages… terrorizing the civilian population; using starvation of civilians to achieve military objectives, the destruction, removal or reduction to uselessness of objects indispensable to their survival … destroying cultural property, historic monuments, places of worship and other objects of cultural or spiritual heritage of peoples …; destroying or capturing enemy property, unless required by military necessity; ordering to pillage a town or place.”[28]

Russia is not alone in violating human, cultural and religious rights.

Kharkiv’s Constructivist skyscraper complex Derzhprom (House of State Industry) in Freedom Square, built in 1928, is in the zone of constant Russian shelling. Photo: Oleksandr Malyon, Wikimedia Commons,

President Putin made a statement on February 21, 2022 the night before the invasion of Ukraine, that Ukrainians are “our comrades, relatives, not only colleagues, friends, but also our family. People we have blood and family ties with.” If the Russian invasion was a form of domestic violence and not a war, then Putin has company among other dictators.

Russia’s extra-territorial claims to controlling heritage and identity are not as unfamiliar and unusual as they seem at first sight. More frequently than through international conflicts, the destruction of heritage takes place domestically, inside Nation States that are United Nations and UNESCO members and signatories to multiple treaties protecting human, cultural and religious rights.

China took Tibet by force, removed its religious rulers from Lhasa and destroyed hundreds of monasteries in Tibet. More than sixty years later, China continues to impose an oppressive, totalitarian government without respect for the lives and liberties of the Tibetan people. In the last ten years, China’s destruction of 15,000 Uyghur cemeteries, shrines, mosques and the ancient built heritage of Kashgar, another World Heritage site, the forcible taking of children and the incarceration of over one million Uighurs in concentration camps is part of an avowed campaign to erase Uyghur identity and replace it with a Chinese one.[29]

Fifty years after expelling its entire Jewish population, Libya has eliminated its Jewish built heritage, from cemeteries to synagogues. Azerbaijan’s president Ilham Aliev has bulldozed thousands of khatchkars and many ancient Armenian churches in Nagorno-Karabag, yet his wife heads Azerbaijan’s UNESCO.[30] In Turkey, President Erdogan’s message to Orthodox Greeks is that while Hagia Sophia may have been the most important remainder of Byzantine culture for 1500 years, now it’s a mosque and a symbol of the triumph of Turkish nationalism.[31]

UNESCO: part of the problem as well as part of the solution

Odesa Museum of Western and Eastern Art, home to Frans Hals masterpieces, Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

It’s time to recognize that the protection of heritage no longer occupies an enlightened special place in international relations.

UNESCO, which does many things well: collecting data, making lists, tracking heritage and reporting, at least selectively, on its destruction, has historically failed to criticize State actors responsible for cultural destruction inside their own borders. Some State actors who have committed the greatest atrocities against minorities inside their borders are members of UNESCO’s inner circle and moreover, like China and Azerbaijan, major contributors to UNESCO.

Although UNESCO still says the words that established its purpose at its founding[32], its failure to act forcefully on them when member States are concerned undercuts its foundational principles, that ‘heritage’ is the shared responsibility of all people, not just national governments. For too long, UNESCO has given primacy to national ownership and bowed at every turn to nationalist claims. Too often, where minority communities are concerned, UNESCO has left behind its vision of heritage as human right – and made it the purview of governments.

The exterior of the Melitopol Museum of Local History in Melitopol, Ukraine, seen before the Russian invasion, Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has been a test of UNESCO’s capacities and reach. While the Russian invasion immediately prompted statements of concern by UNESCO and by cultural institutions around the world for the safety of Ukraine’s museums, cultural institutions and five World Heritage monuments, UNESCO responded by announcing on March 4, 2022 that it would “mark as quickly as possible key historic monuments and sites across Ukraine with the distinctive emblem of the 1954 Hague Convention, an internationally recognized signal for the protection of cultural heritage in the event of armed conflict.” This apparently had no effect.[33]

Less than two months after the invasion began, on April 20, Lazare Eloundou Assomo, director of UNESCO’s World Heritage Centre, announced that nearly 100 culturally important sites in Ukraine had been destroyed.[34] Assomo was clear on how broadly the destruction impacts Ukrainian lives: “City centers are seriously damaged, some of which have sites and monuments that date back to the 11th century. It is a whole cultural life that risks disappearing.”[35]

Russia’s abandonment of its legal obligations under the 1954 Hague Convention (and its second protocol enhancing protection of cultural sites) was an open acknowledgement that it no longer held preservation of heritage as an international obligation. As far as Russia is concerned, heritage has nothing to do with global responsibilities to mankind. Far from being a “vector of peace for the future, which the international community has a duty to protect and preserve,” as UNESCO Director Audrey Azoulay recently stated[36], in the hands of Putin and the Russian military, heritage is a tool to be used in Russian national interest, another weapon for its war.

[1] Russian President Putin Statement on Ukraine, February 21, 2022, CSPAN, https://www.c-span.org/video/?518097-2/russian-president-putin-recognizes-independence-donetsk-luhansk-ukraines-donbas-region

[2] Zelensky slams Russian strikes on Ukraine culture center, Straits Times, May 21, 2022, https://www.straitstimes.com/world/europe/zelenksy-slams-russian-strikes-on-ukraine-culture-centre

[3] Russia’s invasion began February 24, 2022. The Ivankiv Museum was burned between Feb. 25 and 27, depending on the source cited.

[4] Recorded war crimes webpage, “The materials can be used as evidence for the criminal prosecution of those involved in crimes under Ukrainian law at the International Criminal Court in The Hague and a special tribunal after its establishment. Send videos and photos.” https://mkip.notion.site/mkip/e9a4dfe6aa284de38673efedbe147b51?v=f43ac8780f2543a18f5c8f45afdce5f7

[5] Tom Seymour, Is Ukraine’s cultural heritage under coordinated attack?,The Art Newspaper, 10 June 2022, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2022/06/10/is-ukraines-cultural-heritage-under-coordinated-attack

[6] Cultural Heritage Monitoring Lab, Virginia Museum of Natural History and Smithsonian Cultural Rescue Initiative, Ukrainian Cultural Heritage Potential Impact Summary, 6 April 2022, https://www.vmnh.net/content/vmnh/uploads/PDFs/research_and_collections/chml/22-0407_ukrainian_cultural_heritage_potential_impact_summary_final2.pdf

[7] Martin Bailey, Seized antiquities sent from Ukraine to go on show at British Museum, The Art Newspaper, 31 May 2022, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2022/05/31/seized-antiquities-sent-from-ukraine-to-go-on-show-at-british-museum

[8] AFP, Ukraine seizes stolen antiquities collection after multiple raids in Kyiv, Al Arabiya, 24 June 2022, https://english.alarabiya.net/News/world/2022/06/24/Ukraine-seizes-stolen-antiquities-collection-after-multiple-raids-in-Kyiv.

[9] New Lines Institute and the Raoul Wallenberg Centre for Human Rights, Independent Legal Analysis of the Russian Federation’s Breaches if the Genocide Convention in Ukraine and the Duty to Prevent, https://newlinesinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/English-Report-1.pdf

[10] Jeffrey Gettleman and Oleksandr Chubko, Ukraine says Russia looted ancient gold artifacts from a museum, NY Times, April 30, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/30/world/europe/ukraine-scythia-gold-museum-russia.html.

[11]Mariupol’s history museum survived WWII but not Russia’s bombardment. NBC, April 29, 2022, https://www.nbcnews.com/video/mariupol-s-local-history-museum-ruined-by-russian-invasion-138906693721

[12] Gareth Harris, Russia bombs Mariupol art school sheltering 400 civilians, Ukraine claims, 21 March 2022, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2022/03/21/mauripol-art-school-bombed-ukraine-russia-war-crisis

[13] Taylor Defoe, Russian Forces Bombed an Art School in Ukraine, Where Hundreds of Civilians Had Taken Shelter, Artnet, March 21, 2022, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/art-school-ukraine-hundreds-civilians-taken-shelter-destroyed-russian-bombs-2087947

[14] Geraldine Kendall Adams, Russian troops ‘targeting cultural workers and looting collections’, Museums Association, 29 April 2022, https://www.museumsassociation.org/museums-journal/news/2022/04/russian-troops-targeting-cultural-workers-and-looting-collections/

[15] Id.

[16] Eileen Kinsella, Directors of Russia’s Top Art Museums and Fairs Are Resigning En Masse, March 4, 2022, ARTnews, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/russian-art-leaders-resign-ukraine-2080776?utm_content=buffer232ed&utm_medium=social&utm_source=facebook.com&utm_campaign=news..

[17] ‘No one can interfere with our offensive’: Hermitage director Michail Piotrovsky compares Russian export of culture to country’s ‘operation’ in Ukraine, The Art Newspaper, June 24, 2022, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2022/06/24/no-one-can-interfere-with-our-offensive-hermitage-director-mikhail-piotrovsky-compares-russian-export-of-culture-to-countrys-operation-in-ukraine

[18] Director of Moscow’s Second World War museum says he is ‘proud’ to be sanctioned over war in Ukraine. The Art Newspaper, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2022/06/01/director-of-moscows-second-world-war-museum-says-he-is-proud-to-be-sanctioned

[19] Max Bearak and Isabelle Khurshudyan, ‘All art must go underground’: Ukraine scrambles to shield its cultural heritage, Washington Post, 14 March 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/03/14/ukraine-odessa-russia-war/

[20] See, Dutch Court: Scythian Gold from Crimea Should Go to Ukraine, October 31, 2021, Cultural Property News, https://culturalpropertynews.org/dutch-court-scythian-gold-from-crimea-should-return-to-ukraine/

[21] Michael Scollon, From Scythians to Goths:’Looting’ Russia Strikes Gold Digging Up Crimean Antiquities, Radio Free Europe, July 4, 2021, https://www.rferl.org/a/crimea-archaeological-treasures-russia/31339510.html

[22] Sophia Kishkovsky, UNESCO report reveals extent of Russian threat to Crimean heritage, 16 September 2021, The Art Newspaper, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2021/09/16/unesco-report-reveals-extent-of-russian-threat-to-crimean-heritage

[23] Crimean Tatars, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crimean_Tatars

[24] Damian Koropeckyj, Cultural Heritage in Ukraine: a Gap in Russian IO Monitoring, Small Wars Journal, January 21, 2022, https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/cultural-heritage-ukraine-gap-russian-io-monitoring

[25] Id. @ 3.

[26] Id. @ 11.

[27] Dr.Brian Daniels, director of research and programs at the Penn Cultural Heritage Center at the University of Pennsylvania, speaking on the current cultural heritage situation in Ukraine before the American Bar Association’s Art & Cultural Heritage Law Committee on May 12, 2022.

[28] Evan Wallach, Russian Leaders Know They’re Committing War Crimes. Their Laws of War Manual Says So, Lawfare Institute, April 25, 2022https://www.lawfareblog.com/russian-leaders-know-theyre-committing-war-crimes-their-laws-war-manual-says-so

[29] See the many reports on Xinjiang cultural destruction of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, https://www.aspi.org.au/.

[30] Kate Fitz Gibbon, UNESCO Exposed, Cultural Property News, March 19, 2019, https://culturalpropertynews.org/unesco-exposed/

[31] Kate Fitz Gibbon, Hagia Sophia Suffers Serious Damage: Walls Peeled and Marble Tiles Shattered, Cultural Property News, July 1, 2022, https://culturalpropertynews.org/hagia-sophia-suffers-serious-damage/

[32] UN actions have been extremely cautious as well. On UN Human Rights Chief Michelle Bachelet’s recent trip to China, she modified criticism of China’s genocide against its minority Muslim population, talking of setting up a working group and issuing only weak protests. See UN Rights chief concludes China trip with promise of improved relations, UN News, 28 May 2022, https://news.un.org/en/story/2022/05/1119302

[33] For a list of UNESCO actions and statements, including the inscribing of Ukrainian borscht cooking on the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding, see UNESCO actions for Ukraine, https://www.unesco.org/en/ukraine-war/actions-timeline.

[34] Catherine Fiankan-Bokonga, UNESCO: deliberate destruction of Ukraine’s cultural heritage could be considered a war crime, Geneva Solutions, April 20, 2022, https://t.co/l7MZg23i0p.

[35] Max Bearak and Isabelle Khurshudyan, ‘All art must go underground’: Ukraine scrambles to shield its cultural heritage, Washington Post, 14 March 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/03/14/ukraine-odessa-russia-war/

[36] Catherine Hickley, UNESCO gravely concerned about damage to Ukrainian cultural heritage, The Art Newspaper, 4 March 2022, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2022/03/04/unesco-gravely-concerned-about-damage-to-ukrainian-cultural-heritage

Maria Prymachenko, "Blue Bull", 1947, Ukrainian postage stamp issued 2020. Ukrposhta, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.

Maria Prymachenko, "Blue Bull", 1947, Ukrainian postage stamp issued 2020. Ukrposhta, CCA-SA 4.0 International license.