White Sands National Monument, New Mexico, USA. This national monument is of white sands dunes composed of gypsum crystal. Photo by Yuya Sekiguchi, 30 December 2009, CCA 2.0 Generic license.

At an ancient lake site in New Mexico’s Tularosa Basin at White Sands National Park, an international research team led by Dr. Matthew R. Bennett has opened up an unexpected view into the past. Dating back to approximately 22,000 years ago—during the frigid conditions of the Last Glacial Maximum—the archaeological team identified a series of mysterious linear drag marks etched alongside human footprints in ancient sediment.These marks appear to be the earliest physical evidence of a human-engineered transportation device: a travois, used to drag heavy loads across the land. The team’s discovery has also open up new questions about the earliest human societies in North America.

A travois is a simple invention: it can be a single pole dragged behind with objects tied to it, but more often to two poles arranged in either a V-shape or an X-shape used to drag items attached to the join over the ground. Historically, indigenous communities across North America employed these devices, pulled by dogs, horses, or people themselves. The travois could carry anything from children to food and firewood to material for constructing shelters. Since travois were built from biodegradable wood and rope, they rarely survive in the archaeological record. That’s what makes this New Mexico discovery literally groundbreaking—it may be the oldest known physical evidence of transportation technology in the world, long predating the invention of the wheel in about the fourth millennium BCE.

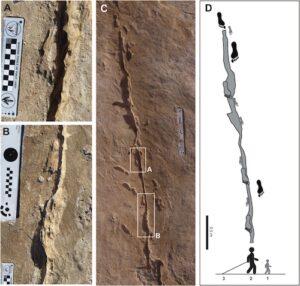

Image from paper, ‘The ichnology of White Sands (New Mexico): Linear traces and human footprints, evidence of transport technology?” Quaternary Science Advances. 2025, Volume 17, January 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.qsa.2025.100274

These intriguing drag marks were found embedded in two key sediment layers. Thanks to a combination of stratigraphic analysis and cutting-edge scientific dating of seeds found in footprints adjoining the tracks, as well as the presence of tracks of megafauna (the proboscidean (afrotherian elephant-like mammals) and giant ground sloth [1] ), both on top of the pole tracks and on adjacent areas, researchers were able to confidently date these surfaces to the Pleistocene, around 22,000 years ago. This pushes back the timeline not only for human technological innovation but also for the early migration of people into North America by several millennia.

The most visually dramatic tracks found are long, narrow grooves (some extending over 50 meters!) that often twist, bifurcate, and cut straight through human footprints. These marks suggest a single pole or log being dragged behind someone—and could possibly be a piece of firewood or a simple travois.

The researchers also found shallow ditches that tended to run straight with wide, flat profiles. This suggests something with a large flat base being dragged.

The final type of marks discovered were double grooves. These are the most compelling evidence of engineered transport. The grooves are evenly spaced between ten and fourteen inches (250-350mm) apart. Human footprints frequently appear between or beside the grooves, indicating that they were formed by a two-poled travois, likely pulled by hand. These tracks show not just technology—but coordination and planning.

Dr. Matthew Bennett kneels on a pad at the excavation site holding a brush. Researchers use brushes to carefully reveal the full impression of footprints found in delicate gypsum sand. These tools allow archeologists to directly work on a print without disturbing the surrounding area. White Sands National Park, 14 January 2020, photo NPS employee, public domain.

The human tracks linked to these drag marks are both varied and numerous, ranging in size from 5 ½ to 11 ½ inches (140 to 295 mm), pointing to their being made by people of all ages. Some tracks may have belonged to children as young as three, others to adults and teenagers, suggesting that groups likely moved together, perhaps with children walking beside or behind adults as they transported goods. Across multiple excavation sites, researchers estimate at least six to seven individuals were involved in creating these traces.

One area, near an eroding bluff, revealed over 90 human tracks and bifurcating grooves—including a touching scene where a child’s tiny footprint is cut by the drag mark of a larger travois.

In another area, grooves were preserved in hardened dolomite, with underlying sediment deformations hinting that these drag marks were made by a travois carrying substantial weight. Two other areas showed evidence of drag marks arranged in intersecting patterns, suggesting that multiple travois were in use simultaneously.

Aerial view of dunefield, White Sands National Park, New Mexico, photo NPS employee, public domain.

And at the White Sands so-called “Mammoth Trample Ground,” researchers discovered drag marks stretching almost 200 feet, even cutting across mammoth tracks—emphasizing just how widespread the use of travois transport may have been.

To test their theories, the team didn’t just speculate—they built travois replicas and headed out to mudflats in the UK and Maine. They dragged both V-shaped and X-shaped travois, with and without loads or padding, observing how V-shaped travois with padding produced marks that closely resembled the real White Sands tracks—especially when they cut directly through human footprints. X-shaped travois made two neat, parallel grooves but left the surrounding footprints untouched.

Geologist Kathleen Springer taking field notes using a notebook at the excavation site. Individual is sitting on the left-side edge of a dugout trench with two fossilized human footprints on the right side. These trenches were created to measure sedimentary layers and determine a timeline using seeds found in between the layers. This timeline would later be used to estimate the date of the footprints. 20 January 2020, White Sands National Park, photo NPS employee, public domain.

The researchers examined other possibilities. Could these marks have been made by mammoth tusks, giant sloths, or even beavers dragging wood? Not likely—none of these animal tracks accompany the grooves. What about firewood or driftwood being dragged? That would not explain the more uniform parallel tracks. As for modern interference—that’s ruled out by clear stratigraphic evidence and buried sediment layers.

All signs point to a community of resourceful, mobile people who had developed practical transport solutions long before the invention of the wheel. The travois they used may have been improvised, possibly doubling as tent poles, firewood, or spears. Indigenous knowledge, shared by the tribal Nations collaborating with the researchers, confirmed that travois use has long been part of cultural narratives of group migration, hunting, and moving shelters.

This discovery is reshaping the way archaeologists think about early innovation. It challenges assumptions about when and how transport technology first emerged, and it offers critical insights into the earliest settlers in North America.

[1] Matthew R. Bennett, Thomas M. Urban, David F. Bustos, Sally C. Reynolds, Edward A. Jolie, Hannah C. Strehlau, Daniel Odess, Kathleen B. Springer, Jeffrey S. Pigati, The ichnology of White Sands (New Mexico): Linear traces and human footprints, evidence of transport technology? Quaternary Science Advances, Volume 17, January 2025, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666033425000103.

USGS geologists Kathleen Springer and Jeff Pigati kneeling over a small plot and taking a very close look at the sedimentary layers.

Test areas were dug into the soil to reveal the individual sediment layers that accrue over time. These layers are useful in determining timeframes and discovering additional objects like seeds that can be used in radiocarbon dating techniques. 20 January 2020. White Sands National Park. Photo by NPS employee, public domain.

USGS geologists Kathleen Springer and Jeff Pigati kneeling over a small plot and taking a very close look at the sedimentary layers.

Test areas were dug into the soil to reveal the individual sediment layers that accrue over time. These layers are useful in determining timeframes and discovering additional objects like seeds that can be used in radiocarbon dating techniques. 20 January 2020. White Sands National Park. Photo by NPS employee, public domain.